The Weekend Watch: Portrait of Jason

Subscriber Exclusive

Welcome to The Weekend Watch, a weekly column focusing on a movie—new, old or somewhere in between, but out either in theaters or on a streaming service near you—worth catching on a cozy Friday night or a lazy Sunday morning. Comments welcome!

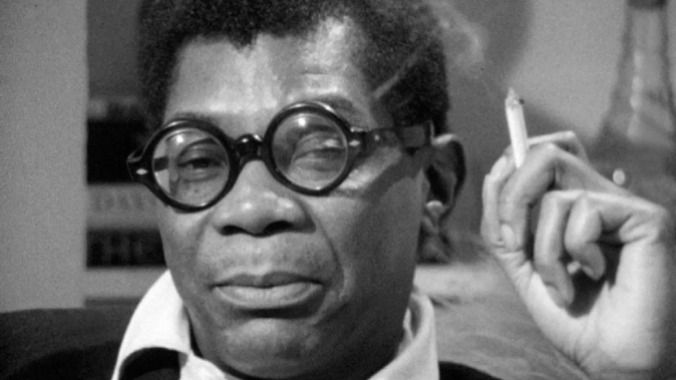

As we get into June, The Weekend Watch continues its focus on queer cinema, this time with one of its classic and most idiosyncratic examinations of queer identity. Portrait of Jason—the 1967 documentary you can find streaming on the Criterion Channel, on your local library’s app Kanopy, or for rent on all the usual services—is all about self-invention, protection and cultivation. Shirley Clarke’s interview with an increasingly intoxicated Jason Holliday AKA Aaron Payne is a revelatory look at the coping mechanisms, and reclamation strategies, of a queer Black man in ‘60s America. At the same time, it paints a much less flattering portrait of filmmakers who are pushing, pushing, pushing—perhaps past the point of artistic integrity and into the realm of boozy, leering exploitation.

That push, from director Clarke and her partner Carl Lee, is included in the relatively vérité film. We hear the two berate Jason off-screen, bringing up times he stiffed them, screwed them over, lied to their faces, lost their cash. We watch as Jason keeps slamming cocktails, dancing the drinker’s familiar steps—laughing, weeping, blabbing, gloating, falling, lying—in whatever order he pleases. These moments add shades of detail and production-based complication to a florid evening of storytelling already layered with complexity. The sensory ephemera of the film’s making-of is so intertwined with what was made that it has inspired its own script-flipping fictionalization, in Stephen Winter’s Jason and Shirley, which offers another angle to a film that already dazzles you with its endlessly glinting facets.

Yes, Portrait of Jason is nonfiction. There’s no script, no “actors” or “roles.” But it’s also…just as fictional as most documentaries. It’s a man, telling stories about his life, in a small room filled with people supplying him with questions, barbs and alcohol. Some of these stories are whoppers, some contain truth so essential they cut to the bone. But at least these are more up-front than so much of what’s currently presented as nonfiction, either in documentary films, reality romance shows or true-crime TV.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-