Gummo and the Tradition of American Cruelty

Discussing Gummo, Harmony Korine’s 1997 directorial debut, has historically brought out a certain vitriol. This statement doesn’t necessarily pertain to cult-movie hounds who have sought out the notoriously non-linear, ultra-low-budget and uniquely abrasive work. Rather, those who have been most publicly incensed by Gummo have largely been the critics assigned to review the film ahead of its (extremely limited) theatrical rollout. In her oft-quoted review of the film, timed to its release 25 years ago, New York Times critic Janet Maslin declared that Gummo was “the worst film of the year,” adding that “when it comes to boy wonders exploring the cutting edge of independent cinema, the buck stops cold right here.”

While Maslin’s might be one of the most memorable derisions of the film, it’s far from the most hostile. “If you were standing in front of me, I’d be tempted to kick your bony ass and hold your head in the john until you apologized for wasting 88 minutes of my time,” wrote The Austin Chronicle’s Russell Smith of Korine. “He named his film ‘Gummo’ after the fifth Marx Brother…Korine failed to mention that of the Marx Brothers, Gummo also was the least talented,” concluded the Chicago Tribune’s Mark Caro. CNN’s Paul Tatara made his piece even more personal: “Gummo is the cinematic equivalent of Korine making fart noises, folding his eyelids inside-out, and eating boogers. Since his outlook is so proudly adolescent, tonight the part of the jock who gives him a wedgie will be played by Paul Tatara.”

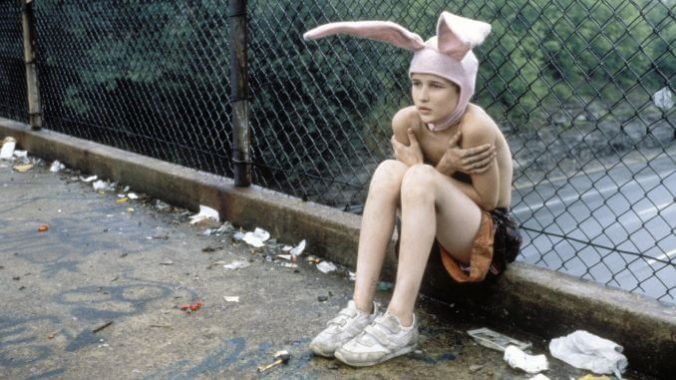

Given how successfully Gummo gets under one’s skin, the critical mean streak for this first-time director (whose only previous film project was writing the script for Larry Clark’s iconically edgy 1995 film Kids) is to be expected. Chronicling the hardship that has come to define the rural locale of Xenia, Ohio ever since a tornado tore through town in the ‘70s, Gummo employs shocking imagery to make a broad observation about the dismal conditions the American underclass is forced to occupy, particularly in the aftermath of a local crisis. Years before civilian outrage over FEMA’s abysmal response to Hurricane Katrina, Gummo asserts that meaningful aid is virtually nonexistent for marginalized populations after disaster strikes.

As a result, the town (and its inhabitants) become increasingly neglected. Teenage protagonists Solomon (Jacob Reynolds) and Tummler (Nick Sutton) make a meager wage as rogue cullers of a robust feral cat population, selling feline carcasses to a local supplier for $1 a pound. Seemingly more emaciated than the boys who hunt them, the slain cats are never very profitable. If they’re lucky, the duo make enough to score a potent tube of glue which they can huff out of a paper bag. Through voiceover narration, Solomon strings together vignettes detailing the equally imperfect livelihoods of other Xenia residents: A neighbor killed by the tornado, a pair of homicidal Jehovah’s Witnesses, his own father’s mugging on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. There’s an absurdity to Solomon’s stories, but they’re grounded by the abject griminess of his surroundings. He huffs glue in a friend’s roach-infested house, eats a spaghetti and chocolate bar dinner while soaking in filthy bathwater and coughs up his hard earned cat-culling money to solicit intimacy from a woman whose own brother sells her for sex. The tragedy inherent to these images is undeniable, but they’re not intended solely to distress audiences. If viewers are made profoundly uncomfortable by the film, it’s because it does such a fantastic job of accurately depicting the human beings this country has relegated to live on the fringes, forced into a life of oppressive, desperate poverty.

And while the critical jabs against Korine are admittedly pretty funny (and he was an admittedly easy target at the time, especially in the wake of his appearances on Letterman), the sentiment critics directed toward the ensemble of non-actors that Korine cast in the film is more odious. They’re referred to as a “menagerie of freaks, mental defectives [and] slatternly rednecks,” “miserable pint-size humans,” “a charter member of White Trash Nation,” “a tubby buck-toothed cheerleader,” “fat retarded daughter,” etc. While these very same critics derided the film for being exploitative, cruel and terribly offensive, they employed virtually no empathy for the real people that Korine effectively captured in their honest essence.

Addressing these allegations of exploitation when it came to his casting of a girl with Down’s Syndrome, specifically, Korine said in 2000 that: “Her beauty is obvious and transcendent to me. And the idea of exploitation means absolutely nothing to me, because I show what I want to see and I don’t exploit people, I don’t make people do things that they don’t want to [do].” This quote, coupled with Korine shooting the film in his hometown of Nashville, Tennessee, reveals that he is acting less as a voyeur and more as a renegade conduit for underground, underrepresented and undervalued voices.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-