Be Trans, Do Crime: By Hook Or By Crook 20 Years Later

In July of 2017, Sam Feder showed an early reel of some of the research that would eventually become Disclosure: Trans Lives On Screen. The 20-minute archival montage, preceded by Feder’s warning that the audience of Outfest Los Angeles’ Trans Summit might find some of the images difficult to stomach, was a rapid, chronological look at some of the more and less well-known images of trans representation over the past 100 years of cinema. A good two thirds of the montage contained scenes where trans or trans-coded characters were ridiculed, murdered, assaulted, or doing the murdering (and always the deception) in turn, and waves of unease and audible sighs ran through the crowd.

It was as if the audience were remembering the shock and visceral mixed emotion of watching every little act of brutality for the very first time—like in the case of Hilary Swank’s portrayal of Brandon Teena in the oft-brandished Boys Don’t Cry, or the infamous twist in The Crying Game. It was mixed catharsis and horror, in which one could see how important it was to tidily confront a history of violence, and be grateful for the chance to watch in a room full of empathetic peers, but that still didn’t make it the kind of watch from which a queer film festival audience might emerge lighthearted and effusive.

Around the final third, however, something on the screen began to change.

Rather than cisgender actors wearing wigs and dresses, or cutting their hair short and affecting a pelvis-forward walk, a handful of trans performers began to make their way into the roles imagining their tortured existence. Alexandra Billings, Candis Cayne and Laverne Cox first made their montage debuts as sex workers on crime procedurals or patients whose hormones were killing them, but within a matter of year-spanning minutes, arrived at the roles now associated with a more positive, since complicated “tipping point.” Orange Is The New Black, Transparent, Dirty Sexy Money and Doubt all crossed the screen, and although there were still setbacks in more recent years (a la The Danish Girl, or Transparent’s since disgraced lead), by the end of the reel, the room settled into a relieved, anticipatory chatter. There was more reason to hope than to fear.

Several years later, Disclosure is now on Netflix, having been released to fairly warm critical and popular reception. It’s become a starter kit of sorts for uncovering some of the psychic damage done to the legitimacy of trans existence by mass media, and is being cited as such: A reference tool that does its best to forward the opinions of trans actors. While I’m thankful to have been involved in the coordination of its Trans Filmmaker Fellowship program, and am grateful that it’s so accessible as a gender and media studies text, in the three years between that Outfest first look and now, there’s one sequence of the montage that I haven’t stopped thinking about, nor stopped wondering why it hasn’t itself become the center of revived appreciation.

The first clip to receive any type of applause and a few whoops from the Outfest audience, which preceded the more popular 2010s installments by at least fifteen years, was simple, intriguing and totally unrecognizable to me. It’s a rapid shot-reverse-shot of two young white people: One with a bloody nose, striped beanie and twisted, wispy beard; the other with short, shiny hair, a bedazzled button down and a totally bemused expression. As they breathlessly run from whatever is chasing them, they stare at each other with wonder and confusion. Who is this person? Do they know me? Are they like me?

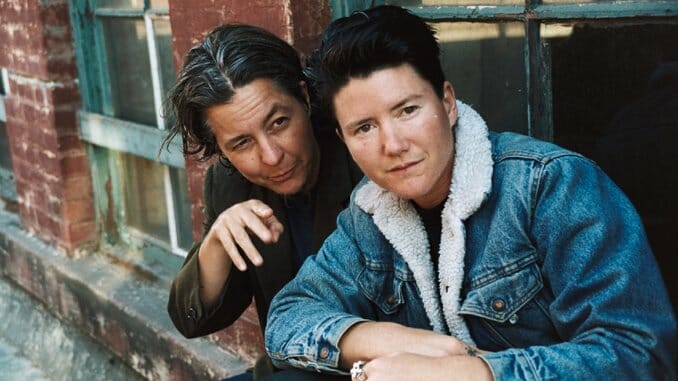

This is the first meeting of Shy (Silas Howard) and Valentine (Harry Dodge), in the nearly perfect, delightfully gender-fucking 2001 buddy comedy By Hook or By Crook. The first feature from co-stars and directors Howard and Dodge, its zany but sincere tone follows the development of their friendship, their individual romances and their greatest fears as they figure out how to survive (and maybe rob a bank) in queer San Francisco. Twenty years after its Outfest premiere, and with the conversation stirred around trans representation made by trans artists, it’s surprising that the digital video caper, available for free on Vimeo, hasn’t had its time in the retroactively deserved spotlight.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-