The 100 Best Sci-Fi Movies of All Time

Much like its close genre cousin (nephew/niece?) the superhero film, the potential of sci-fi movies exploded in the latter part of the 20th century thanks to technological advances that transformed special effects. Unlike superhero films, which were so stunted for so long that almost every new one makes it onto our updated 100 Best Superhero Films of All Time list, science fiction proved fertile ground for filmmakers before the likes of Industrial Light & Magic supercharged a director’s ability to exceed our imagination. Thus, this list, while filled with films from the ’80s onward, has its fair share of older films. Before we dive into it, though, let’s discuss a few things this list will not have (or at least, not have many of).

Superhero films are for the most part absent. Though so many superhero stories involve the stuff of science fiction—aliens, high-tech and strange worlds—there are plenty of great sci-fi movies to include on this list without bumping 20 of them off for DC and the MCU. We’ve also left off, for the most part, the traditional giant monster/kaiju movie for the same reason. If you want a nice roundup of Godzilla’s greatest hits, check out our own Jim Vorel’s ranking of Godzilla’s cinematic oeuvre. (For the real kaiju rank-o-phile, Jim has also taken the measure of every Godzilla monster.) Finally, joining superheroes and kaiju on the sidelines, are the post-apocalyptic (and a few mid-apocalyptic) films. Though, again, there are a few exceptions, for the most part you will not find Mad Max here, or Eli, or even that guy who is Legend. (I see you frowning—“But will there be dystopias,” you ask? Hell yeah, we got dystopias.)

As you’ll see below, that leaves plenty of great films. As we go about our lives with appliances more powerful than the super computers of a few decades ago, take a few hours here and there to check out some of these you haven’t seen and to revisit some you have. Chuckle at those futuristic visions that now seem all too quaint, marvel at those that still blow your mind, and perhaps squirm uncomfortably as you watch those that strike a bit too close to home.

Here are the 100 best sci-fi movies of all time:

100. A Trip to the Moon (1902)

Director: George Méliès

While A Trip to the Moon only lasts 15 minutes, it still feels epic (plus, that runtime wasn’t considered so short in 1902). In turn, this light, colorful (make sure you watch the hand-painted, restored version) collage of whimsy follows a premise that would go on to serve sci-fi adventure films for more than a century: People embark on a journey and crazy shit goes down. With its long, stagy takes and flat compositions, the primitive nature of the film is apparent, but Méliès makes up for it with charm. Modern viewers instinctively know how to spot basic camera trickery, especially when perspective and scale aren’t quite right. Méliès, however, understood his limitations, embraced the artifice and, with that moon face taking a rocket to the eye, created something iconic. —Jeremy Mathews

99. Antiviral (2012)

Director: Brandon Cronenberg

When you’re the son of David Cronenberg, you have a lot to live up to in a horror film debut, and Brandon Cronenberg does an admirable job in his cerebral and icky horror flick Antiviral. Although it can be a little slow and portentous, the setting and ideas are spectacular. The film imagines a near-future, sci-fi tinged world where obsession with celebrity lives has replaced nearly every other facet of the arts. People are so celebrity-obsessed, in fact, that a booming genetics business has developed to cater to disease hounds—people who literally want to be injected with specific strains of diseases, such as STDs, that have been harvested from various starlets. Elsewhere, people stand in line at meat markets to buy muscle tissue grown and cultivated from celebrity donors. Cronenberg may lay the social commentary on a little thick, but the results on screen are chilling. Cronenberg creates a setting that one is never really able to dismiss from the mind ever again. —Jim Vorel

98. Alphaville (1965)

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Science-fiction isn’t particularly suited to Godard’s gaze—so erratic and tongue-in-cheek, so uninterested in the exigencies and peculiarities of world-building is the legendary French director—but there is also no better visionary to attack the mind-fuck that is this weirdo Lemmy Caution adventure. Alphaville is as much an experimental noir as it is speculative fiction, steeped in the tropes of the former while blissfully tinkering with the world of the latter, never quite justifying the hybridizing of both but never quite caring, either. As such, the pulpy story of a secret agent (Eddie Constantine) who’s sent into the “galaxy” of Alphaville to assassinate, amongst a few, the creator of the artificial intelligence (Alpha 60) which runs all facets of Alphavillian society by pretty much outlawing all emotion—meanwhile falling in love with the daughter of the inventor (Godard muse Anna Karina)—is as goofy as it is compelling, fully committed to the confusing premise and aware, as most Godard films are, of the leaps required of the audience to follow the meandering plot. Saturated with anachronism and stylized to the point of parody, Alphaville isn’t interested in immersing a viewer in a not-so-distant dystopian future as it is in laying bare science fiction as a genre which demands we dramatically re-conceptualize everything about the genre we take for granted: language, humanity and a future we’ll at least kind of understand. —Dom Sinacola

97. Sleeper (1973)

Director: Woody Allen

Sleeper’s sci-fi slapstick is Woody Allen comedy at the peak of the legendary filmmaker’s powers. Miles Monroe (Allen), as a cryogenically unfrozen man out of time, is drafted into an underground resistance movement against a tyrannical, robot-enforced police state. (In today’s political climate, its prescience feels eerie, if obvious.) What follows is pinpoint physical comedy, hilariously Allen-esque one-liners and some side-splittingly funny sight gags (not to mention the incomparably talented Diane Keaton) pervading the future dystopian America of 2173. Thankfully, for Miles, the police state of the future is evidently more incompetent than him. Would that we were so lucky today. —Scott Wold

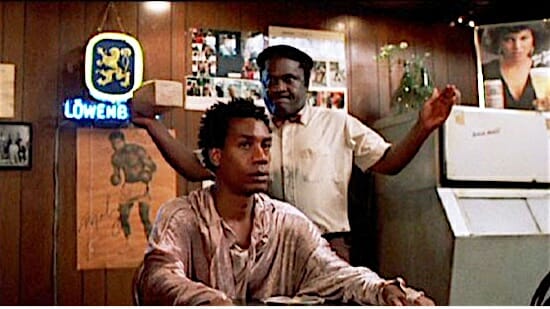

96. The Brother from Another Planet (1984)

Director: John Sayles

During the ’80s, John Sayles established himself as a smart indie writer/director with a knack for social commentary, but only one of his films embedded said commentary into a zany sci-fi plot. The result is the story of a mute alien who looks like a black man with weird feet, who crash-lands in Harlem and meets and observes the people of New York City. Joe Morton gives a stellar silent performance that, like the film itself, seamlessly moves from comic to empathetic. —Jeremy Mathews

95. Outland (1981)

Director: Peter Hyams

Two years after Alien, Peter Hyams blew up the blue-collar subtext of Ridley Scott’s grimy mining vessel politics to remake High Noon in space. In perhaps his noblest role, Sean Connery plays Federal Marshal William O’Niel, a rigorous do-gooder assigned to duty shepherding the motley crew of titanium ore miners inhabiting a station on the Jupiter moon of Io. Like any burgeoning colony on the borders of civilization, law and order automatically succumbs to whatever criminal hierarchy supplies the vices required to prevent the workers from devolving into total madness—but nobody told O’Niel. Principled to a fault and still reeling from the sudden departure of his wife and son—fed up with one too many assignments to shitty outposts far away from an Earth their son has never seen—O’Niel decides to stand alone against the confederacy of capitalist evil saturating the already dysfunctional society slowly springing up on Io, led by by smarmy corporate boss Mark Sheppard (Peter Boyle). From there, Hyams stages a tense stand-off between O’Niel and the bureaucratic assassins sent to teach him what’s what (i.e., murder him) leading to a fatal game of cat and mouse in which O’Niel’s hopelessly outnumbered, though the cramped quarters and unforgiving void of space can be worked to his advantage. Rather than relegate the exploration of the cosmos to only the elite, Hyams (with directors like Scott and John Carpenter) serves as cinematic tributary for the proletariat, knowing that what awaits us off planet isn’t an escape from the institutionalized suffering of most of us on Earth, but a continuation of that human tragedy into a much more alien, unforgiving environment. The more it seems we’ll need to find a way to outlive this world—our world—the more we’ll have to come to terms with what we won’t be able to leave behind. —Dom Sinacola

94. Dual (2022)

Director: Riley Stearns

In Dual, everyone talks like they’re a robot. Perhaps that’s because they want to better integrate new Replacements, clones made of terminally ill or otherwise on-their-way-out people, into the world. Maybe it’s because the delivery is supposed to be as dry, strange and winning as the low-key sci-fi itself. Regardless, this idiosyncratic acting choice by writer/director Riley Stearns is just one of many over the course of his third and (so far) best movie. The world of Dual is near-future, or present-adjacent but in another dimension. Its video chat is Zoom-like, but texting has more of a coding aesthetic. Its minivans still run on gas, but you can make a clone out of spit in an hour. Its people still love violent reality TV, but its shows sometimes involve government-mandated fights to the death between people who discover they’re no longer dying and their Replacements. It’s the latter situation in which Sarah (Karen Gillan) finds herself. After puking up blood, creating a clone to take over her life and receiving improbable good news from a scene-stealingly funny doctor, Sarah finds that she has a year to prepare for the fight of (and for) her life. Stearns shoots the film in grim, hands-off observations sapped of color and intimacy, but with amusing angles or choices (like a long take watching characters do slo-mo play-acting) that add visual energy to the bleakness. As we see this unfurl, we root for Sarah’s success not because we want her to get her old, sad life back, but because the training process has opened her up to life beyond those walls. It can be read as a redemptive allegory representing a life-shaking break-up or other crisis, but Stearns’ deadpan script and wry situations rarely give you enough distance to consider Dual beyond the hilarious text in front of you. Gillan goes beyond a cutesy Black Mirror performance to find tragedy, obscene humor and warmth even in her relatively stoic roles, but the shining star of the show is Aaron Paul, who gets the biggest laugh lines as her intense combat instructor. Somewhere between a living instruction manual and the “Self-Defense Against Fresh Fruit” Monty Python sketch, Paul’s character is a riot as he attempts to familiarize Sarah with weapons and desensitize her to violence. His performance is just as committed as his serious scene partner’s, but when the two are in the groove together, Dual transcends to such big-hearted, surreal silliness that I had a hard time calming my laughter down as the film reminded me that death was on the line. Stearns’ work has always been a bit of a specific flavor, a little like that of Yorgos Lanthimos where if you’re not in on the dark joke you can feel ostracized from the universe of the movie, and Dual is both his most successful and most eccentric yet. But if you’re blessed with matching taste, where you’ll put up with a bunch of over-literal, stiff-backed oddballs dealing with a clone crisis, you’ll find a rewarding and gut-busting film that’s lingering ideas are nearly as strong as its humorous, thoughtful construction.—Jacob Oller

93. The Vast of Night (2020)

Director: Andrew Patterson

The Vast of Night is the kind of sci-fi film that seeps into your deep memory and feels like something you heard on the news, observed in a dream, or were told in a bar. Director Andrew Patterson’s small-town hymn to analog and aliens is built from long, talky takes and quick-cut sequences of manipulating technology. Effectively a ‘50s two-hander between audio enthusiasts (Sierra McCormick and Jake Horowitz playing a switchboard operator and disc jockey, respectively) the film is a quilted fable of story layers, anecdotes and conversations stacking and interweaving warmth before yanking off the covers. The effectiveness of the dusty locale and its inhabitants, forged from a high school basketball game and one-sided phone conversations (the latter of which are perfect examples of McCormick’s confident performance and writers James Montague and Craig W. Sanger’s sharp script), only makes its inevitable UFO-in-the-desert destination even better. Comfort and friendship drop in with an easy swagger and a torrent of words, which makes the sensory silence (quieting down to focus on a frequency or dropping out the visuals to focus on a single, mysterious radio caller) almost holy. It’s mythology at its finest, an origin story that makes extraterrestrial obsession seem as natural and as part of our curious lives as its many social snapshots. The beautiful ode to all things that go [UNINTELLIGIBLE BUZZING] in the night is an indie inspiration to future Fox Mulders everywhere. —Jacob Oller

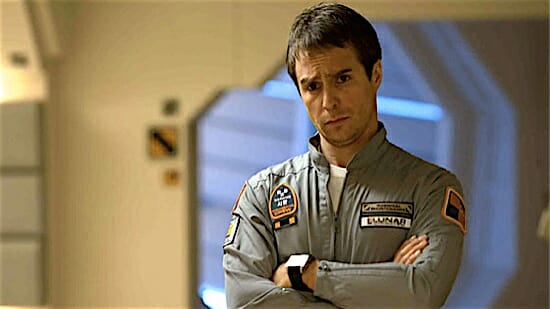

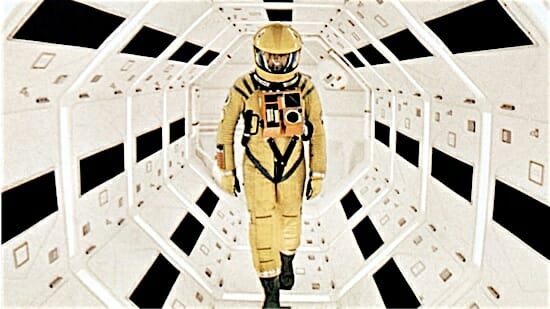

92. Moon (2009)

Director: Duncan Jones

First-time director Duncan Jones is overt about his stylistic appropriations of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, right down to the sweeping orchestral music that frames the opening shots of the titular satellite and Earth. Yet, where Kubrick tapped into existential fears about human extinction and the future of civilization, Jones hypothesizes the logical conclusion of that dark vision: a world where the need for more energy has rendered humanity a manufactured cog of multinational corporations whose reach now extends beyond the boundaries of Earth. The film’s plot centers on Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell), the only human on a lunar mining facility that harvests Helium-3, a clean fuel that can meet a near-future Earth’s ballooning energy demands. Base computer system GERTY (Kevin Spacey) is his sole companion on Sam’s three-year caretaking mission, since a supposed satellite failure means he can only send and receive pre-recorded messages. When an accident nearly kills Sam, he’s saved by a clone of himself and begins to unravel the sinister nature of the base, and his existence. Moon cribs heavily from the retro-futuristic look of ‘60s and ‘70s sci-fi for its claustrophobic and sanitized depiction of the moon base, but this high-tech eye candy is only the backdrop to a larger morality tale about humanity’s ever-shrinking position within a technologically-saturated society. When the human experience can be synthesized (and thus made disposable), does such a thing as “humanity” even exist? There’s a host of challenging philosophical threads throughout—cloning, masculinity, energy, corporate power—but those individual issues complement rather than engulf the larger narrative. Moon is a superlative example of science fiction that hearkens to the genre’s roots: social commentary on the human condition, without the easy catharsis of overblown special effects and space opera. It’s the ultimate rarity in modern cinema: a mature, engaging and thoughtful sci-fi movie, and proof that there’s life yet left in the genre. —Michael Saba

91. Galaxy Quest (1999)

Director: Dean Parisot

Galaxy Quest is a film about equilibrium between love and parody; a movie made with less of the former and too much of the latter becomes a mean-spirited dunk on sci-fi fandom, and a movie made in the reverse becomes too much about fan service than honest-to-goodness storytelling. Dean Parisot, aided and abetted by writers David Howard and Robert Gordon, finds the perfect balance of both, and Galaxy Quest gets to be a straight-up sci-fi adventure flick that embraces its genre as enthusiastically as it pokes fun at its tropes. You don’t make that kind of affectionate self-satire without caring. It’s not like sci-fi fandom couldn’t stand a little dunking, after all, but only a real sci-fi fan knows where to draw the line. So Parisot, Howard and Gordon must be real sci-fi fans. Much as Galaxy Quest picks away at the conventions of its category, and at the people who worship sci-fi with as much reverence as the average Baptist praises Jesus, it’s built on an abiding fondness for Star Trek: For phasers, for warp drives, for teleportation, for holograms, for alien races exotic and bizarre, for every other damn cliché in the sci-fi playbook that makes us groan but which we know we couldn’t quite live without. (What’s a good sci-fi movie without a brash, macho commander who makes questionable strategic calls that somehow work anyway?) This one’s for the sci-fi fans. And if you’re not a sci-fi fan, then it might be the movie to make you into one. —Andy Crump

90. The Hidden (1987)

Director: Jack Sholder

Though John Carpenter’s The Thing steeped the then-terrifyingly mysterious AIDS crisis in otherworldly horror five years before, The Hidden indulges in similar tropes and identical themes with blunter, no-less-pulpier mayhem. LA detective Thomas Beck (Michael Nouri) must reluctantly work with FBI Special Agent Gallagher (Kyle Maclachlan, pretty much playing a proto-Dale Cooper) to get to the bottom of a spate of violently incomprehensible murder sprees seducing otherwise normal, mild-mannered citizens—only to discover, when it’s much too late, that the culprit is an alien slug parasite passed orally from host to host, giving each unlucky husk superhuman vulnerability and a nihilistic mean streak. The sci-fi fare of the late ’80s too often succumbed to the cynicism of an overcommercialized zeitgeist, seeing in corporate America and the Reagan administration’s response to every social crisis the death knell of whatever good vibes speculative fiction once had to offer, but with The Hidden—violent and brutal in its own right—came, in the film’s final moments, a gesture of sacrifice and genuine compassion unusual for a genre flick of its ilk. Or, at least, that’s one way to interpret it. —Dom Sinacola

89. Westworld (1973)

Director: Michael Crichton

Long before there was Jurassic Park (or the increasingly frustrating Westworld HBO series, for that matter), Michael Crichton wrote (and directed) the story of another disastrous theme park: Delos, housing the sophisticated amusement android characters of Westworld, Medievalworld and Romanworld. After catastrophic malfunctions inevitably occur, a couple dudes enjoying Dude Time find themselves menaced for real, when the robotic “bad guy” Gunslinger’s safety measures disappear. And a decade before there was The Terminator, there was Yule Brenner’s implacable robot stalker, an unfeeling killing machine who happens to look exactly like Brenner’s heroic character from The Magnificent Seven. Don’t bother trying to melt his face, Peter (Richard Benjamin); there are plenty more where that came from. “Boy, have we got a vacation for you!” promises the ads for the park. They weren’t wrong. —Scott Wold

88. Independence Day (1996)

Director: Roland Emmerich

They pretty much don’t make action movies like Independence Day anymore, although if you ask someone who caught Independence Day: Resurgence, they’ll tell you that’s probably a good thing. Regardless, there’s a certain sheen to this particular brand of FX-driven pre-2000s disaster blockbuster, an earnestness of conviction in terms of clear-cut characters like Jeff Goldblum’s “David Levinson”—call it a willingness to believe that the audience will be 100 percent on board with a protagonist from the very beginning, rather than questioning his methods. As for the rest of the cast, we get a who’s who of ’90s delights, whether it’s an ascendant, wisecracking Will Smith—one year before Men in Black would cement him as leading man material—or Bill Pullman as the flyboy American president ready to deliver one of cinema’s greatest jingoistic addresses. Independence Day doesn’t shy away from its inspirations as pulp (it might as well be a remake of Earth vs. The Flying Saucers as far as the alien motivations are concerned) but it dresses up its Saturday morning cartoon plot with undeniably ambitious spectacle, even when viewed 20-plus years later. That exploding White House, not to mention the effortless camaraderie of Goldblum and Smith in all their scenes together, cement Independence Day among the most rewatchable sci-fi action films of the past two decades. —Jim Vorel

87. Silent Running (1971)

Director: Douglas Trumbull

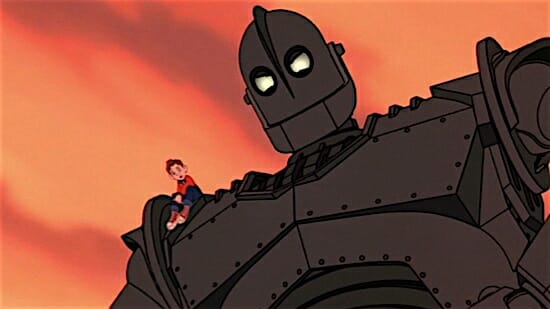

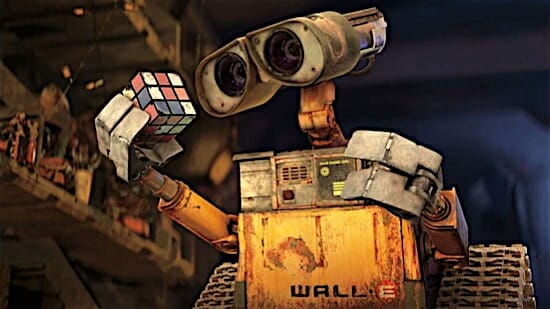

A precursor to both Wall-E and Moon, Silent Running was the first feature directed by Douglas Trumbull, the special-effects wizard best known for his work on 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and The Tree of Life. Set on a spaceship hovering around Saturn, this meditative film concerns an interstellar greenhouse custodian named Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern) who’s keeping watch over the last of Earth’s forests and wildlife. When Lowell is told to destroy his payload and return to Earth, he refuses, deciding instead to fake an accident and pilot his ship into the farthest reaches of space, where he and his living wards will be safe from human interference. Ecologically conscious, narratively simple, deeply affecting, Silent Running is one of those great lost gems of 1970s sci-fi. —Tim Grierson

86. Nine Days (2021)

Director: Edson Oda

In a small house, alone in the desert, Will (Winston Duke) watches. Nine Days, the wrenching feature debut from writer/director Edson Oda, understands that we are an existence of voyeurism. We’re only truly living to our fullest when we can see, share, feel the experiences of others. Will is a sort of hiring manager for life itself. As painful as it is for him to accept (he’s obviously grown fond of his previous picks), there is a new vacancy, and there are a few candidates. Over a nine-day process, almost like an audition for a reality show—especially fitting considering that the plane they would leave behind houses a watcher carefully and compassionately taking in a televised wall of literal life-streams—Will and his friend/co-worker Kyo (Benedict Wong) whittle down the applicants to find the best person suited for the gift of worldly existence. Oda’s compact, stirring, metaphysical sci-fi stageplay about the ends and beginnings of life—and all the wonder ripe for the sharing contained between—is as moving a debut as you’ll see all year. First, it takes some real creative brass to try to tackle such an ambitious, heady and easily trite topic. Second, it takes some major storytelling talent—both in the crafting of the script and the handling of its actors—to overcome those obstacles while keeping the dignity of all involved intact. Nine Days has quiet confidence, written in the way that some of the best sci-fi is, where it feels like a massive text that’s been erased down to the barest elements necessary for a perception imagination to piece together—a painting of overwhelming sentiment depicted with the simplest strokes possible. Oda’s script has been visualized with a similar restraint, nearly contained to Will’s home and its screens before it slowly pushes at these boundaries. But, at first at least, Will’s hopefuls—including Tony Hale, Bill Skarsgård, David Rysdahl, Arianna Ortiz and a last-minute Zazie Beetz—are roped into routine. As the would-be humans continue to prove themselves through a series of psychological tests, their growth or stagnation metered out in compellingly restrained segments overseen by Duke’s stoic yet compassionate shepherd, we become as invested as Will in their prospects. The gravity of what they’re after hits us. The ultra-sincere Charlie Kaufman/Spike Jonze-esque premise (Jonze executive produced the film) moves beyond its high concept and starts digging into its emotional implications. Scene after scene of appreciation for the magical moments of life hammer our hearts. Rarely do movies so tenderly tenderize you. It can be shatteringly bittersweet even without the soaring strings of Antonio Pinto’s score, and when they come in, it’s not even fair. Admirably ambitious and bracingly sincere, Nine Days leaves you raw and refreshed. Nine Days marks Oda as one of our most exciting new directors, a filmmaker possessing an innovative cinematic mind with a heart to match.—Jacob Oller

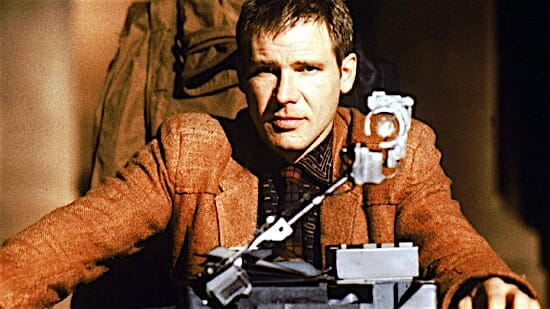

85. Strange Days (1995)

Director: Kathryn Bigelow

Before she reinvented herself as the director of award-winning docudramas, Kathryn Bigelow made her name directing crazy genre movies like Near Dark and Point Break. With all respect to Point Break, however, Strange Days remains Bigelow’s most compelling pre-War on Terror project. Written by Bigelow’s former husband James Cameron and Oscar-nominated screenwriter Jay Cocks, Strange Days is a pulpy, noir-influenced sci-fi pic in the vein of Blade Runner but with more high-octane action and a lot more nudity. Developed in the era of the videotaped Rodney King beatings and the L.A. riots, the film is set in a dystopian Los Angeles where people’s memories and experiences are recorded directly from their brains to sell on the black market. Anyone who has ever wanted to experience criminal activities or perverse sexual encounters can now do so without repercussions. The trouble begins when vice-detective-turned-black-marketer Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes) discovers a “snuff” disc depicting the brutal murder of an acquaintance. This disc leads him down a rabbit hole into the urban underground. At nearly two and a half hours, the film’s visual pyrotechnics and beautifully stylized performances provide more than enough ammunition to justify such excess. —Mark Rozeman

84. Snowpiercer (2013)

Director: Bong Joon-ho

There is a sequence midway through Snowpiercer that perfectly articulates what makes Korean writer/director Bong Joon-ho among the most dynamic filmmakers currently working. Two armies engage in a no-holds-barred, slow motion-heavy action set piece. Metal clashes against metal, and characters slash through their opponents as if their bodies were made of butter. It’s gory, imaginative, horrifying, beautiful, visceral and utterly glorious. Adapted from a French graphic novel by Jacques Lob, Benjamin Legrand and Jean-Marc Rochette, Snowpiercer is a sci-fi thriller set in a futuristic, post-apocalyptic world. Nearly two decades prior, in an ill-advised attempt to halt global warning, the government inundated the atmosphere with an experimental chemical that left our planet a barren, ice-covered wasteland. Now, the last of humanity resides on “Snowpiercer,” a vast train powered via a perpetual-motion engine. Needless to say, this scenario hasn’t exactly brought out the best of humanity. Bong’s bleak and brutal film may very well be playing a song that we’ve all heard before, but he does it with such gusto and dexterous skill you can’t help but be caught up the flurry.—Mark Rozeman

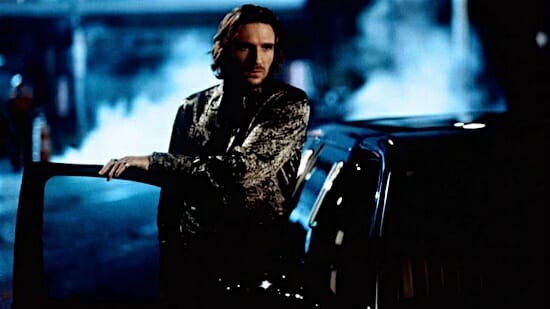

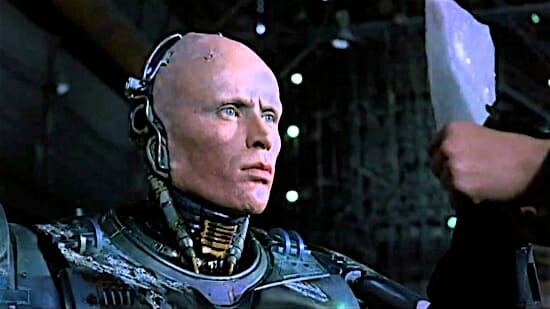

83. Dark City (1998)

Director: Alex Proyas

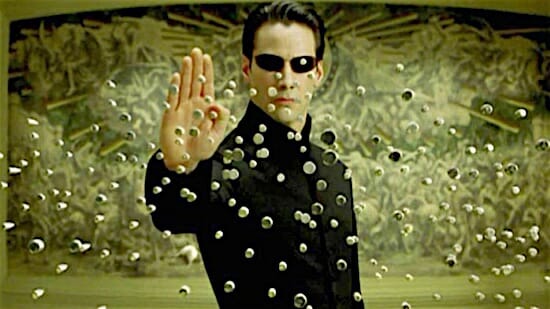

Alex Proyas’s magnum opus serves up a cerebral sci-fi extravaganza as filtered through the visual tropes of film noir and German Expressionism. A staggering achievement in imagination, Dark City, like clear predecessor Blade Runner, flopped at the box office only to be revived later as a beloved cult classic. The film casts Rufus Sewell as amnesiac John Murdoch who wakes up one night to discover that his city is (quite literally) under the manipulation of a band of mysteriously pale men in jet-black trench coats and fedoras. Along for the ride is Kiefer Sutherland as a crazed scientist and Jennifer Connelly as the femme fatale, our hero’s estranged wife.

One might also draw a straight line between this and The Matrix, released a year later. The similarities between the two films’ visual styles and themes of slavery, techno-rebellion and free will are nigh-impossible to miss, and many visual essays have been written specifically to compare the two movies. John Murdoch’s arc is only slightly less portentous than that of the prophesied One (Keanu Reeves) in The Matrix—both are seemingly normal men scooped up and thrust into a web of slowly untangling secrets while discovering that they possess special powers that will eventually allow them to defeat the puppetmasters who created their reality. The two films were even largely filmed at the same studio—Fox Studios Australia—and possess a similar green-tinged patina of unreality. Ultimately, Dark City is a bit more philosophically aloof than the popcorn-munching, easier to grasp Matrix, which is probably the reason the latter eventually became a cultural touchstone. But Dark City deserves to be seen, both on its own merits and as an exercise to see which of its sights may have lodged in the mind of the Wachowskis, waiting to be reborn in the next year’s blockbuster. —Mark Rozeman and Jim Vorel

82. A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Director: Steven Spielberg

A.I. may be Spielberg’s misunderstood masterpiece, evidenced by the many critics who’ve pointed out its supposed flaws only to come around to a new understanding of its greatness—chief among them Roger Ebert, who eventually included it as one of his Great Movies ten years after giving it a lukewarm first review. A.I. represents the perfect melding of Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick’s sensibilities—as Kubrick supposedly worked on the story with Spielberg, and Spielberg felt obliged to finish after Kubrick’s death—which allows the film to keep each of their worst instincts in check. It’s not as cold or distant as Kubrick’s films tend to be, but not as maudlin and manipulative as Spielberg’s films can become—and before the ending is brought out as proof of Spielberg’s failure, it should be noted that the film’s dark coda was actually Kubrick’s idea, adamant that the ending not be meddled with moreso than any other scene. A closer inspection of the film’s themes reveal a much bleaker conclusion—and, no, those aren’t “aliens.” —Oktay Ege Kozak

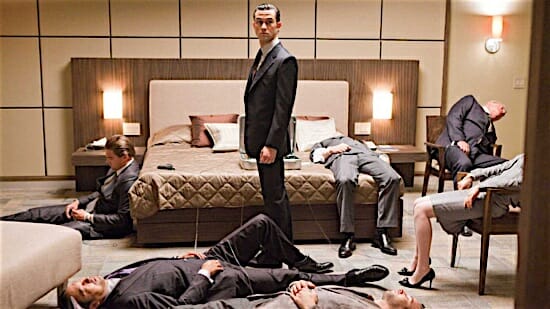

81. Inception (2010)

Director: Christopher Nolan

In the history of cinema, there is no twist more groan-inducing than the “it was all a dream” trope (notable exceptions like The Wizard of Oz aside). With Inception, director Christopher Nolan crafts a bracing and high-octane piece of sci-fi drama wherein that conceit isn’t just a plot device, but the totality of the story. The measured and ever-steady pace and precision with which the plot and visuals unfold, and Nolan mainstay wally Pfister’s gorgeous, globe-spanning on-location cinematography, implies a near-obsessive attention to detail. The film winds up and plays out like a clockwork beast, each additional bit of minutia coalescing to form a towering whole. Nolan’s filmmaking and Inception’s dream-delving work toward the same end: to offer us a simulation that toys with our notions of reality. As that, and as a piece of summer popcorn-flick fare, Inception succeeds quite admirably, leaving behind imagery and memories that tug and twist our perceptions—daring us to ask whether we’ve wrapped our heads around it, or we’re only half-remembering a waking dream.

Director Andrei Tarkovsky wrote a book about his philosophy towards filmmaking, calling it Sculpting in Time; Nolan, on the other hand, doesn’t sculpt, he deconstructs. He uses filmmaking to tear time apart so he can put it back together as he wills. A spiritual person, Tarkovsky’s films were an expression of poetic transcendence. For Nolan, a rationalist, he wants to cheat time, cheat death. His films often avoid dealing with death head-on, though they certainly depict it. What Nolan is able to convey in a more potent fashion is the weight of time and how ephemeral and weak our grasp on existence. Time is constantly running out in Nolan’s films; a ticking clock is a recurring motif for him, one that long-time collaborator Hans Zimmer aurally literalized in the scores for Interstellar and Dunkirk. Nolan revolts against temporal reality, and film is his weapon, his tool, the paradox stairs or mirror-upon-mirror of Inception. He devises and engineers filmic structures that emphasize time’s crunch while also providing a means of escape. In Inception different layers exist within the dream world, and the deeper one goes into the subconscious the more stretched out one’s mental experience of time. If one could just go deep enough, they could live a virtual eternity in their mind’s own bottomless pit. “To sleep perchance to dream”: the closest Nolan has ever gotten to touching an afterlife. —Michael Saba and Chad Betz

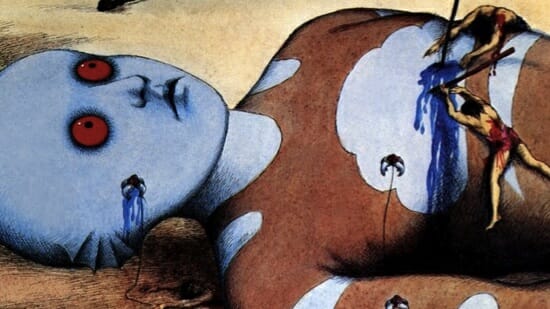

80. Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Director: Mamoru Oshii

It’s difficult to overstate how enormous of an influence Ghost in the Shell exerts over not only the cultural and aesthetic evolution of Japanese animation, but over the shape of science-fiction cinema as a whole in the 21st century. When Ghost in the Shell first premiered in Japan, it was greeted as nothing short of a tour de force that would later go on to amass an immense cult following when it was released in the states. The film garnered the praise of directors such as James Cameron and the Wachowski siblings (whose late-century cyberpunk classic The Matrix is philosophically indebted to the trail blazed by Oshii’s precedent).

Adapted from Masamune Shirow’s original 1989 manga, the film is set in the mid-21st century, a world populated by cyborgs in artificial prosthetic bodies, in the fictional Japanese metropolis of Niihama. Ghost in the Shell follows the story of Major Motoko Kusanagi, the commander of a domestic special ops task-force known as Public Security Section 9, who begins to question the nature of her own humanity surrounded by a world of artificiality. When Motoko and her team are assigned to apprehend the mysterious Puppet Master, an elusive hacker thought to be one of the most dangerous criminals on the planet, they are set chasing after a series of crimes perpetrated by the Puppet Master’s unwitting pawns before the seemingly unrelated events coalesce into a pattern that circles back to one person: the Major herself.

Everything about Ghost in the Shell shouts polish and depth, from the ramshackle markets and claustrophobic corridors inspired by the likeness of Kowloon Walled City, to the sound design, evident from Kenji Kawai’s sorrowful score, to the sheer concussive punch of every bullet firing across the screen. Oshii took Shirow’s source material and arguably surpassed it, transforming an already heady science-fiction action drama into a proto-Kurzweil-ian fable about the dawn of machine intelligence. Ghost in the Shell is more than a cornerstone of cyberpunk fiction, it’s a story about what it means to craft one’s self in the digital age, a time where the concept of truth feels as mercurial as the net is vast and infinite. —Toussaint Egan

79. District 9 (2009)

Director: Neill Blomkamp

Let’s begin with a number: 30 million. That’s how much money Neill Blomkamp spent to make District 9, a movie small in scale but great in ambition, look like it cost four times that amount. Years later, Blomkamp’s career hasn’t realized the full promise shown in District 9, but here, he looks like a guy knows what he’s doing all the same. A genre stew blended from varying measurements of Alien Nation, Watermelon Man, Independence Day, The Fly and RoboCop, District 9 treads familiar territory in an unfamiliar place, through an unfamiliar lens, splicing documentary-style filmmaking together with stomach-churning body horror and, by the end, high-end action spectacle.

Nine years ago, the end results of Blomkamp’s mad sci-fi cocktail felt revelatory. Today they feel disappointing, a remark on what he could have been and where his career might have taken him if he’d not lost himself in the morass of Elysium or turned off even his more devoted followers with Chappie. All the same, District 9 remains a major work for a first-timer, or even a third-timer, polished and yet scrappy at the same time; the film tells of an artist with something to say, and saying it with electric urgency. —Andy Crump

78. Attack the Block (2011)

Director: Joe Cornish

Written and directed by Joe Cornish, the sci-fi action comedy centers on a gang of teenage thugs—particularly their disgruntled leader, Moses, remarkably underplayed by a young John Boyega—and their housing project in South London. When the defiant juveniles take their crime to a new level and mug an innocent nurse (a delightful Jodie Whittaker), they immediately find themselves plagued by alien invaders. These hideous creatures, with their jet black fur and glowing blue fangs, want nothing more than to destroy the boys and their tower block.

In the spirit of Spielberg—even more so than J.J. Abrams’ Spielberg ode of the same year, Super 8—Cornish uses alien beings as the catalyst to bring supernatural redemption to a person and a community. He focuses specifically on London’s socioeconomic bottom half and the turmoil surrounding them, exposing the lies that society’s youth buy into that prolong cultural discontinuity. A comical scene, in which Moses tries to make sense of the aliens while giving excuses for his criminal behavior, highlights this cleverly—he doesn’t just blame the government for violence and drugs in his neighborhood, he blames the government for the whole alien invasion.

Cornish, however, doesn’t simply confront this hopeless attitude, he points toward hope—most vividly in the way Moses battles the aliens, his fight rapt with symbolic implications. Though he tries to escape the beasts through running and avoidance, he realizes he must inevitably face them, but not on his own. In Attack the Block, the alien invasion becomes one giant metaphor for the darkness that binds Moses, his friends and his block—a threat that can only be countered with the pivotal power of community. —Maryann Koopman Kelly

77. Upstream Color (2012)

Director: Shane Carruth

Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color builds a stunning mosaic of lives overwhelmed by decisions outside their control, of people who don’t understand the impulses that rule their every action. Told with stylistic bravado and minimal dialogue (none in the last 30 minutes), the film continually finds new ways to evoke unexpected feelings. The visuals—from stunning shots of underwater schist to microscopic photography—combine with extraordinary sound design and rhythmic cross-cutting to create a hypnotic portrait of the story’s intertwined narratives. The means to the interconnectivity is a small worm whose parasitic endeavors link lives together, but Carruth doesn’t bother with sci-fi exposition. The organism does what it does, and that’s all we need to know. This allows more time to explore the emotional impact the organism has on the characters. Ultimately, that’s where Upstream Color succeeds. An elaborate intellectual concept fuels the film, but a rich sense of humanity gives it power. —Jeremy Matthews

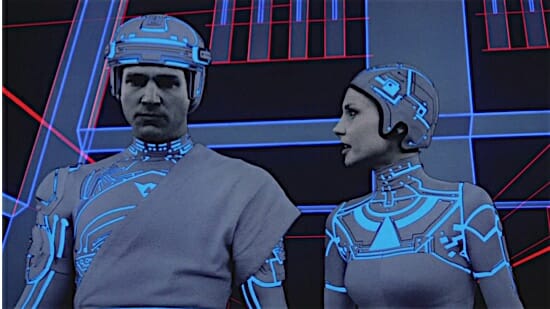

76. Tron (1982)

Director: Steven Lisberger

In a movie in which computer programmers—so-called “users”—are revered as gods, no one really programs much of anything. It’s understandable: The early ’80s presented mind-boggling technology, once reserved for academics and elites, to the masses, and it all seemed like magic. Steven Lisberger’s Tron writes that awe into its code, building a world within a computer as a theocracy (populated by “programs” who carry out their existences serving a single function) ruled on religious oppression. The godhead is power-hungry AI MCP (Master Control Program) who, presaging James Cameron’s Terminator films, intends to surpass its human progenitors, the deified users, to take over the “real” world, making sinister moves like hacking into the Pentagon and the Kremlin and then being a cocky asshole about it. Suave engineer Flynn (Jeff Bridges) just wants credit for the video game he created, which turned ENCOM—the company he helped found as a forefather of the MCP—into an international juggernaut before his partner (David Warner) plagiarised him and kicked him from the top of the corporate ladder. Infiltrating the ENCOM building to try to dig up evidence of the betrayal, Flynn, just as annoying as the MCP, is digitalized, sucked into the company’s computer network via a laser (housed in “Laser Bay 1,” according to the buttons on the elevator), wherein, disguised as a program, he discovers just how fascist coding can get. And, like Neo in The Matrix, Flynn learns he can manipulate the fabric of this reality, taking up his new quasi-mystical role with relish, later going full be-robed Jedi bathed in beatific neon light for 2010’s Tron: Legacy. “All that is visible must grow beyond itself and extend into the realm of the invisible,” says Dumont (Barnard Hughes), an oracular figure and the closest the film gets to a digital priest. Tron, and so much of sci-fi, is a sign of just how spiritually charged that growth can be. —Dom Sinacola

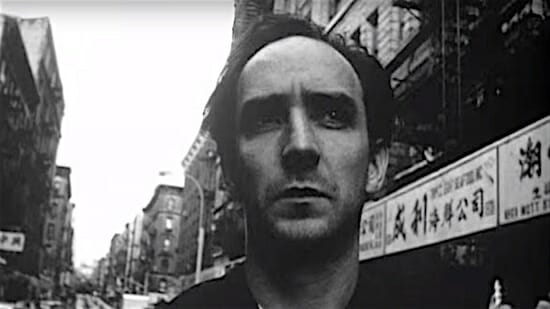

75. Pi (1998)

Director: Darren Aronofsky

Pi feels like an 85-minute migraine. That’s a good thing.

Darren Aronofsky, American master of the cinematic freakout, fittingly got his start with a film that brings us into the head of a man on the verge of a mental breakdown. For this guy, a math whiz named Max Cohen (Sean Gullette) who got his PhD at 20 and spends his days crunching numbers in a dingy New York apartment, the world is one big equation to be solved. Applying a mind quick enough to multiply 322 by 491 in a fraction of a second, Max intends on unlocking the patterns of the universe—the symmetries, recursions and ratios that will enable him to, among other things, predict the trajectory of the stock market, which he sees as an organism abiding by natural laws. For him, this quest is about pushing both technology and the human body further than they’ve ever gone before and so is, as is often the case with most sci-fi exploring the brink of understanding—of a new reality—hubristic in nature, though other parties intend to exploit his brain for different reasons. A posse of Wall Street big shots want to buy his stock market data to turn a profit, while a group of Hasidic Jews seek his help in deciphering the Torah, which they believe involves decoding the numerical basis of the Hebrew language. As outside interference and, above all, internal drive push Max to and beyond the brink of collapse, Pi seems on the verge of disintegrating with him, so closely does it hew to the man’s subjective experience.

To do this, the film shows us the things that a mentally-spent Max hallucinates: a singing subway passenger, a man with a bloodied hand and, most strikingly, a disembodied brain that literalizes the film’s own status as an externalization of its protagonist’s mind. These oneiric visions imbue the movie with a nightmarish aura evoking the surrealism of David Lynch. Appropriately, Pi’s most obvious Lynchian forebear is Eraserhead, given the Aronofsky film’s black-and-white aesthetic, otherworldly aura, slimy imagery, character of the alluring woman-next-door and grating soundtrack courtesy of Clint Mansell, whose hellish soundscape brilliantly evokes how tinnitus might sound if cranked to 11.

Three times throughout the film, Max recounts a childhood incident where his mom told him not to stare into the sun. He did anyway and impaired his vision as a result. The most obvious point of reference here is the myth of Icarus, the classic admonishment against unchecked ambition explicitly referenced elsewhere in the film, but also evoked is Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” which tells of an underground prisoner who, raised to believe that projected shadows on a wall were the original Things themselves, is freed from ignorance and allowed to step above ground into the light. In that story, the liberated man is blinded by sunlight after having spent his life in the dark, but with Max, what’s unclear is whether the sun is a transcendent truth or the fires of his own obsession obstruct the clarity that he’s been trying so hard to grasp. —Jonah Jeng

74. Looper (2012)

Director: Rian Johnson

Joseph-Gordon Levitt channels his inner badass to act as the younger version of Bruce Willis, nailing (with the help of some CGI and prosthetics) Willis’s ubiquitous action presence. The best case made on film for “If time travel is outlawed, only outlaws will have time travel!”, writer/director Rian Johnson wisely treats the tech as a given, focusing instead on the dramatic scenarios humans’ use of it would create. The result is one of the more thrilling time-travel-infused flicks of the last few decades, and one obvious reason why Johnson was trusted with a Star Wars film not long afterward. —Christian Becker

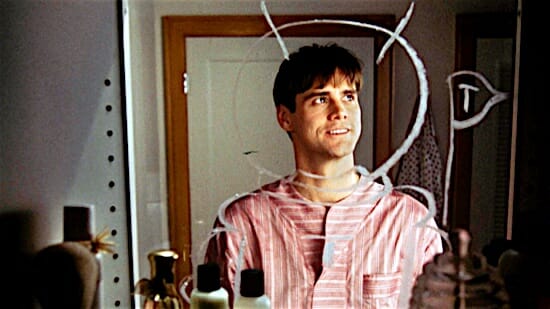

73. The Truman Show (1998)

Director: Peter Weir

Peter Weir’s delightful, hilarious The Truman Show wouldn’t get made anymore. It’s a star-studded event film centered around a simple and dystopian premise: Jim Carrey’s eponymous character has unwittingly been raised from birth as a reality TV star and only now has begun to suspect that everybody in his life is a hired actor. Carrey’s clear-eyed acting is worlds away from the zany roles that catapulted him to fame a few short years prior, though, as was typically the case with Carrey roles in the ’90s, copious amounts of special effects work go toward creating a believable simulated reality for Carrey’s endearing everyman to be trapped within. The heartfelt monologues and devastating revelations as he fights to escape his gilded cage shine all the brighter for it. The fight to break away from control, from a sanitized and curated existence dictated by a literal white father figure in the sky, rings alarmingly two decades years later, when social media has made performative brand managers of us all. Truman is an unlikely and often hapless hero in his own story, but his eventual hijacking of his own narrative—and his final defiance of his literal and figurative creator figure—form one of the most heroic cinematic arcs of the last 20 years. —Kenneth Lowe

72. The Chronicles of Riddick (2004)

Director: David Twohy

Space Opera. So easy to dismiss, yet, as with many of the pulpy confections of the imagination, so hard to get just right. Fifth Element gets it right. Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets gets it wrong (though just wrong). David Twohy and Vin Diesel’s sequel to Pitch Black, however, is cooked to perfection, with noir-tinged dialogue and distress, existential threats both personal and planet-wide, and outlandish events and crazy characters presented with earnestness. The Chronicles of Riddick avoids exposition overload, though it manages to sneak in plenty of world-building, as our titular Furian kicks antagonist ass from one scene to the next. In some ways, the series as a whole can be compared to the Alien franchise—the first film horror, the second all action, the third, well, less exciting—but the second film of the series stands out as one of the purest, most enjoyable encapsulations of space opera outside the land of Lucas. —Michael Burgin

71. Okja (2017)

Director: Bong Joon-ho

Okja takes more creative risks in its first five minutes than most films take over their entire span, and it doesn’t let up from there. What appears to be a sticking point for some critics and audiences, particularly Western ones, is the seemingly erratic tone, from sentiment to suspense to giddy action to whimsy to horror to whatever it is Jake Gyllenhaal is doing. But this is part and parcel with what makes Bong Joon-ho movies, well, Bong Joon-ho movies: They’re nuanced and complex, but they aren’t exactly subtle or restrained. They are imaginative works that craft momentum through part-counterpart alternations, and Okja is perhaps the finest example yet of the wild pendulum swing of a Bong film’s rhythmic tonality.

Okja is, in other words, the culmination of Bong’s unique rhythms into something like a syncopated symphony. The film opens with Tilda Swinton’s corporate maven Lucy Mirando leering out an expository dump of public relations about her new genetically created super-pigs, which will revolutionize the food industry. We’re also introduced to Johnny Wilcox, played by Gyllenhaal as a bundle of wretched tics, like there’s a tightly-wound anime character just waiting to rid itself of its Gyllenhaal flesh, but in the meantime barely contained. Okja is the finest of the super-pigs, raised by a Korean farmer (Byun Hee-bong) and his granddaughter Mija (Ahn Seo-hyun), an orphan. Okja is Mija’s best friend, a crucial part of her family. Bong takes his sweet time with this idyllic life Mija and Okja share. The narrative slows down to observe what feels like a Miyazaki fantasy come to life. Mija whispers in Okja’s ear, and we’re left to wonder what she could possibly be saying. The grandfather has been lying to Mija, telling her he has saved money to buy Okja from the Mirando corporation. There is no buying this pig; it is to be a promotional star for the enterprise. When Johnny Wilcox comes to claim Okja (a sharp note of dissonance in the peaceful surroundings) the grandfather makes up an excuse for Mija to come with him to her parents’ grave. It is there he tells her the truth.

Mija’s quest to rescue Okja brings her in alliance with non-violent animal rights activists ALF, which ushers the film into a high-wire act of an adventure where Bong’s penchant for artful set-piece is pushed to new heights. The director works with an ace crew frontlined by one of our greatest living cinematographers, Darius Khondji, who composes every frame of Okja with vibrant virtuosity. The very action of the film becomes action that is concerned with its own ethics. As the caricatures of certain characters loom larger, and the scope of the film stretches more and more into the borderline surreal, one realizes that the Okja is a modern, moral fable. It’s not a film about veganism, but it is a film that asks how we can find integrity and, above all, how we can act humanely towards other creatures, humans included. The answers Okja reaches are simple and vital, and without really speaking them it helps you hear those answers for yourself because it has asked all the right questions, and it has asked them in a way that is intensely engaging. —Chad Betz

70. High Life (2019)

Director: Claire Denis

High Life begins with a moment of intense vulnerability, followed immediately by a moment of immense strength. First we glimpse a garden, verdant and welcoming, before we’re ushered to a sterile room. There we realize there’s a baby alone while Monte (Robert Pattinson), her father maybe, consoles her, talking through a headset mounted within his space helmet. “Da da da,” he explains through the intercom; the baby starts to lose her shit because he’s not really there, he’s perched outside, on the surface of their basic Lego-piece of a spaceship, just barely gripped on the edge of darkness. They’re in space, one supposes, surrounded by dark, oppressive nothingness, and he can’t reach her. They’re alone. Next, Monte empties their cryogenic storage locker of all the dead bodies of his once-fellow crew members, lifting their heavy limbs and torsos into space suits, not because it matters, but maybe just because it’s something to do to pass the time, as much a sign of respect as it is an emotional test of will. Monte looks healthy and capable, like he can withstand all that loneliness, like he and his daughter might actually make it out of this OK, whatever this is. High Life lives inside that juxtaposition, displaying tenderness as graphically as violence and anger and incomprehensible fear, mining all that blackness surrounding its characters for as much terror as writer-director Claire Denis can afford without getting obvious about it. Pattinson, flattened and lithe, plays Monte remarkably, coiled within himself to the point that he finishes every word deep in his throat, his sentences sometimes total gibberish. He doesn’t allow much to escape his face, but behind his eyes beams something scary, as if he could suddenly, and probably will, crack. He says as much to Willow, his kid, whispering to her while she sleeps that he could easily kill them both, never wanting to hurt her but still polluting her dreams. He can’t help it, and neither can Denis, who, on her 14th film (first in English), can make an audience believe, like few other directors, that anything can happen. Madness erupts from silence and sleep, bodily fluids dripping all over and splattering throughout and saturating the psyches of these criminal blue collar astronauts, the overwhelming stickiness of the film emphasizing just how intimately close Denis wants us to feel to these odd, sick fleshbags hurtling toward the edge of consciousness. —Dom Sinacola / Full Review

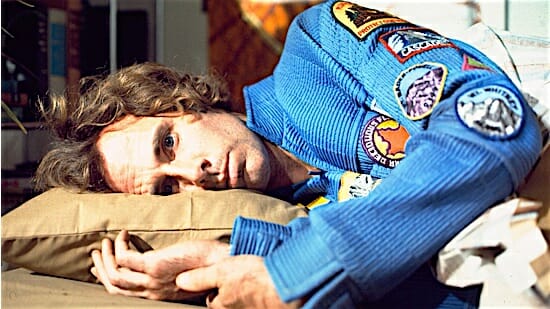

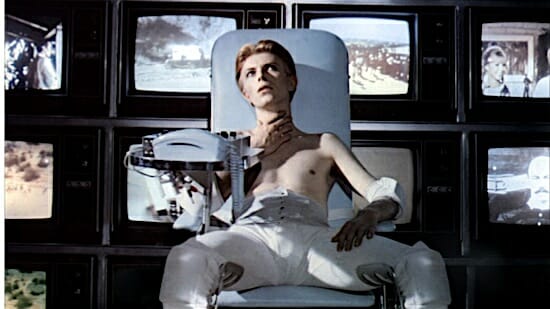

69. The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Director: Nicholas Roeg

Imbued with newfound poignancy and melancholia after the passing of its mercurial lead Starman, David Bowie, Nicholas Roeg’s impressionistic, ravenous, experiential masterpiece is one of the rare films about aliens that feels as exotic in its form as its content. Filled with Roeg’s characteristically discursive, paradoxically symmetrical but nonlinear cutting and violently sensual imagery, The Man Who Fell to Earth is as much about subverting the very nature of human experience as it is about offering an outside window into our culture. As the “secretive, but not private” Thomas Jerome Newton—a meteoric billionaire industrialist whose knowledge allows him to skip decades of scientific stranglehold at a mere moment—Bowie’s version of a universal traveler is less about a misunderstanding of the world than a semantic confusion of the pronunciation of words, or an inability to reinforce his own externalized narrative. Even as Newton leaps every known scientific hurdle, his life force is slowly being wrung out by competitors and friends alike who are so consumed with success they’re unable to see the big picture, or recognize the importance of Newton’s own interest in returning to his family. In what both represents and replicates the experience of watching a Roeg film, Newton obsesses over dozens of televisions, attempting to collectively view reality as one congealed experience. As he explains, “Television shows you everything, but it doesn’t tell you everything.” Moving decades in single frames, Newton can’t escape this misery of his own making, basking in the death of his memories over endless gins as he experiences seemingly multiple lifetimes in a single event. Referring to his eternal imprisonment, Rip Torn’s traitorous Nathan Bryce asks, “Are you mad that we did this?” On the verge of passing out, Newton responds, “We’d have probably treated you the same if you came over to our place.” Even aliens aren’t immune to our vices of apathy and despair. —Michael Snydel

68. Re-Animator (1985)

Director: Stuart Gordon

Ironically, the most entertaining take on H.P. Lovecraft is the least Lovecraftian. Stuart Gordon established himself as cinema’s leading eldritch adaptor with a juicy take on the story “Herbert West, Re-Animator,” about a student who concocts a disturbingly flawed means of reviving the dead. Re-Animator more closely resembles a zombie film than the author’s signature brand of occult sci-fi, but it boasts masterful suspense scenes, sharp jokes and Barbara Crampton as a smart, totally hot love interest. Jeffrey Combs as West establishes himself as the Anthony Perkins of his generation, a hilariously insolent and reckless genius he’d go on to play in two Re-Animator sequels. (Combs even played Lovecraft in the anthology film Necronomicon.) Re-Animator is a near-perfect crystallization of the best aspects of ’80s horror, delighting in its perversion as much as its awesomely grotesque practical effects. —Curt Holman

67. Gattaca (1997)

Director: Andrew Niccol

Less given to gadgetry and special effects than deeply felt characters, Andrew Niccol’s 1997 film envision a near-future in which almost all children are lab-created and genetically modified to prevent any mental or physical “imperfections.” Ethan Hawke stars as Vincent, a “God child” conceived naturally and therefore irrevocably flawed. In order to pursue his ambitious career dreams, Vincent seeks help from a DNA broker and assumes a new, genetically superior identity. Archetypal in construction, the film uses a beautiful orchestral score by veteran composer Michael Nyman (The Piano) to evoke an atmosphere that both melancholic and reflective, layered over impeccable production design. The film’s every visual element, from color saturation to sound design, assists in immersing viewers in an atmosphere, like those beings one semantic step from being synthetic, simultaneously familiar and completely alien. —Kara Landhuis

66. Evolution (2015)

Director: Lucile Hadžihalilovic

Hadžihalilovic’s gorgeous enigma is anything and everything: creature feature, allegory, sci-fi headfuck, Lynchian homage, feminist masterpiece, 80 minutes of unmitigated gut-sensation—it is an experience unto itself, refusing to explain whatever it is it’s doing so long as the viewer understands whatever that may be on some sort of subcutaneous level. In it, prepubescent boy Nicolas (Max Brebant) finds a corpse underwater, a starfish seemingly blooming from its bellybutton. Which would be strange were the boy not living on a fatherless island of eyebrow-less mothers who every night put their young sons to bed with a squid-ink-like mixture they call “medicine.” This is the norm, until Nicolas’s boy-like curiosity begins to reveal a world of maturity he’s incapable of grasping, discovering one night what the mothers do once their so-called “sons” have fallen asleep. From there, Evolution eviscerates notions of motherhood, masculinity and the inexplicable gray area between, simultaneously evoking anxiety and awe as it presents one unshakeable, dreadful image after another. —Dom Sinacola

65. Twelve Monkeys (1995)

Director: Terry Gilliam

Terry Gilliam takes Chris Marker’s La Jetée and makes it grimier. Beginning in post-apocalyptic Philadelphia in 2035, Twelve Monkeys glimpses Earth’s surface as contaminated by a virus that forces survivors to hide underground. Cole (Bruce Willis) must travel back to the ’90s to collect information on this deadly virus, but, of course, nothing goes as planned. While Cole questions his sanity, he must not only find a way to escape the mental institution in which he’s been placed, but he must also race against fate to undo his ultimate undoing. A cauldron of plot twists, excellent performances and environmentalism, Twelve Monkeys makes an inarguable case for inevitable human doom. —Christian Becker

64. Contact (1997)

Director: Robert Zemeckis

Contact seems almost calculated as the sort of cerebral sci-fi to frustrate multiplex audiences with its philosophical, open-ended conclusion about “first contact,” questioning whether any of what Jodie Foster’s character experienced really happened at all. Still, Contact is a beautiful film about the struggle between the tangible and the ephemeral, between faith, intellect and ambition. Ellie (Foster) is innately sympathetic, a woman with a selfless streak who nonetheless on some level seeks a very personal validation in being chosen as humanity’s representative to meet an alien race. The film challenges us to consider the depth of our inconsequential standing in the universe, and how different aspects of humanity, both beautiful and hideous, would present themselves after the revelation of a “higher power.” Add to this an impressive cast that includes Foster, John Hurt, James Woods, William Fichtner, Rob Lowe, Tom Skerritt, David Morse and Matthew McConaughey (years before his McConaissance), and you can overlook the presence of Jake Busey in one of the best examples of “hard sci-fi” in the 1990s. —Jim Vorel

63. THX 1138 (1971)

Director: George Lucas

The brilliance behind George Lucas’s choice to have his dystopic society disciplined via android cops is that there’s little difference between the machines who keep the “peace” and the people for whom they’re keeping it. Resembling a sort of campy take on highway patrolmen (think the Village People, except with way less singing) spliced with G.I. Joe’s Destro, the robot police force is governed solely on “budget,” which of course allows our hero THX (Robert Duvall) to escape the underground society, and the mysterious deity, OMM 0910, that represses him. Yet, in being left to his own devices after OMM determines that chasing after THX would put the robot police force 6% “over budget,” even THX’s humanity is further reduced to a matter of balancing numbers. It may be a point of triumph for our protagonist, but in perhaps the most subtle thematic move the director has ever made, Lucas is implying that even the organic characters in THX 1138 are mere tools for a higher power. —Dom Sinacola

62. Edge of Tomorrow (2014)

Director: Doug Liman

Major William Cage (Tom Cruise) spends his days in the film’s near-future setting spinning the armed forces’ ongoing efforts against a hostile alien race (dubbed Mimics) without ever setting foot on a battlefield. At least until a gruff general (Brendan Gleeson) sends him on a particularly dicey mission. The result is Cage’s death, but the story doesn’t end there. Instead Cage awakes at the beginning of the day he died with his memory intact, and quickly discovers the resurrections will recur every time he dies. His only hope of escaping the endless cycle lies with super-soldier Rita Vrataski (Emily Blunt), who knows from experience exactly how Cage might be able to use this new ability to help humanity win the war of the worlds. Based on the manga All You Need Is Kill by Hiroshi Sakurazaka and adapted for the screen by Christopher McQuarrie (Cruise’s current go-to director completely in sync with his physically-defying action spectacle) and Jez and John-Henry Butterworth, Edge of Tomorrow recalls other notable time loop sagas, including Groundhog Dayand Source Code in the witty and engaging way it moves its story forward piece by piece. As Cage relives the same day over and over again, he also learns how to become a true soldier, trains with (and falls for) Rita, discovers how the aliens function and ever so patiently formulates the perfect plan of attack. Like a video game hero with infinite lives, Cage has the opportunity to refine and correct every mistake he makes along the way. However long Cage is on that journey, Edge of Tomorrow is a blast, and Cruise carries the surprisingly amusing action like a pro—his skill with deadpan comedy proving even more valuable than his infamous enthusiasm for sacrificing his flesh over and over and over. —Geoff Berkshire

61. Return of the Jedi (1983)

Director: Richard Marquand

Look, I’m not here to defend Ewoks. Really, I’m not. But there’s a certain subset of Star Wars fans who go really profoundly overboard on their Ewok hang-up. Yes, the little fuzzballs probably could have been phased out of Episode VI altogether, but outside of them, the film offers the most incredible action sequences and epic conclusion of the entire series. So please, forget about the Ewoks for one moment and appraise the film on the rest of its merits. It’s all here: Incredibly varied settings, from the grime of Jabba’s palace to the overgrowth of Endor and the cold, steely sparseness of Imperial command ships. A fully matured Luke (Mark Hamill) proves that his powers have grown considerably, that he’s not simply chasing “delusions of grandeur” in the rescue of Han (Harrison Ford). And then there’s the true introduction of Palpatine as the face of ultimate evil—is there any more badass way to introduce a character for the first time than for Darth Vader, who we’ve personally witnessed choke numerous officers to death for trivial offenses, to say, “The Emperor is not as forgiving as I am”? The space battle above Endor is the greatest that the series has ever produced, and probably ever will produce (the only thing that comes close is the conclusion of Rogue One); the sheer scale and dizzying choreography that ILM managed to pull off with practical effects in 1983 is still one of the most amazing VFX feats in cinema history. And the ultimate confrontation between Luke, Vader and the Emperor is the tipping point of the entire trilogy’s arc: Luke’s final test—both of his Jedi resolve and his deep-seated belief in the spark of Anakin Skywalker left burning deep within Vader. The moment when Luke casts his lightsaber down and declares himself to be “a Jedi, like my father before me,” bringing a bitter scowl to the Emperor’s crestfallen face, is an emotional triumph. —Jim Vorel

60. Avatar (2009)

Director: James Cameron

![]()

It makes sense that Avatar is still the highest grossing movie ever made: Irony and insincerity have no place in its extended universe. Whether or not James Cameron intended to crib the world of Pandora and its futuristic inhabitants from practically every fantastical ur-text ever conceived, it hardly matters, because Avatar is modern mythmaking at its most foundational. Cameron still seems to believe that “the movies” can give audiences a transformative experience, so every sinew of his film bears the Herculean effort of truly genius worldbuilding, telling the simple story of Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) and his Dances with Wolves-like saving of the Na’vi, natives to the planet of Pandora, from the destructive forces of colonialism. Cameron wants us to care about this world as much as Jake Sully, and by extension James Cameron, does, crafting flora and fauna with borderline sociopathic obsessiveness, at the time pushing 3-D technology to its brink to bring his inhuman imagination alive. It worked; “unobtanium” is actually a real thing. Four sequels feels like a disgusting gambit for a man whose ambition may have long ago outpaced his sense of storytelling, or sense of reason, or sense of what our oversaturated, over-franchised culture can even stomach anymore. But Cameron’s proven us wrong countless times before. —Dom Sinacola

59. Interstellar (2014)

Director: Christopher Nolan

Whether he’s making superhero movies or blockbuster puzzle boxes, Christopher Nolan doesn’t usually bandy with emotion. But Interstellar is a nearly three-hour ode to the interconnecting power of love. It’s also his personal attempt at doing in 2014 what Stanley Kubrick did in 1968 with 2001: A Space Odyssey, less of an ode or homage than a challenge to Kubrick’s highly polarizing contribution to cinematic canon. Interstellar wants to uplift us with its visceral strengths, weaving a myth about the great American spirit of invention gone dormant. It’s an ambitious paean to ambition itself. The film begins in a not-too-distant future, where drought, blight and dust storms have battered the world down into a regressively agrarian society. Textbooks cite the Apollo missions as hoaxes, and children are groomed to be farmers rather than engineers. This is a world where hope is dead, where spaceships sit on shelves collecting dust, and which former NASA pilot Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) bristles against. He’s long resigned to his fate but still despondent over mankind’s failure to think beyond its galactic borders. But then Cooper falls in with a troop of underground NASA scientists, led by Professor Brand (Michael Caine), who plan on sending a small team through a wormhole to explore three potentially habitable planets and ostensibly secure the human race’s continued survival. But the film succeeds more as a visual tour of the cosmos than as an actual story. The rah-rah optimism of the film’s pro-NASA stance is stirring, and on some level that tribute to human endeavor keeps the entire yarn afloat. But no amount of scientific positivism can offset the weight of poetic repetition and platitudes about love. —Andy Crump

58. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is, quite simply, the film responsible for the creation of Studio Ghibli. It not only signaled Miyazaki’s nascent status as one of anime’s preeminent creators, but also sparked the birth of an animation studio whose creative output would dominate the medium for decades to come. Following the release of The Castle of Cagliostro, Miyazaki’s odd Lupin III adventure, the director was commissioned by his producer and future long-time collaborator Toshio Suzuki to create a manga in order to better pitch a potential film to his employers at Animage. What resulted was Nausicaä, a fantasy-sci-fi epic inspired by the works of Ursula K. Le Guin and Jean “Moebius” Giraud, starring a courageous warrior princess trying to mend a rift between humans and the forces of nature while soaring across a post-apocalyptic wilderness. Nausicaä was the film that introduced the world to the motifs and themes for which Miyazaki would become universally known: a courageous female protagonist unconscious of and undeterred by gender norms, the surmounting power of compassion, environmental advocacy and an unwavering love and fascination with the phenomenon of flight. It spawned an entire generation of animators, among them Hideaki Anno, whose lauded work on the film’s climactic finale would later inspire him to go on to create Neon Genesis Evangelion. The essentialness of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind’s placement within the greater canon of animated film, Japanese or otherwise, cannot be overstated. —Toussaint Egan

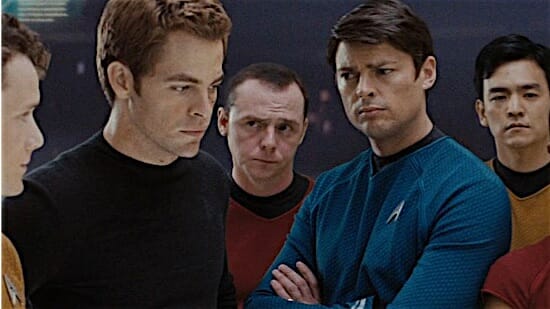

57. Star Trek (2009)

Director: J.J. Abrams

J.J. Abrams’ slick movie reboot of the Star Trek franchise is essentially a louder, flashier and sexed-up take on the ’60s television show. While it eschews the series’ usual M.O. of sci-fi-as-social-commentary, it’s largely faithful to the source material and features a top-shelf ensemble cast. Star Trek resurrects the idealistic flights of fancy of pre-’70s sci-fi, and offers us a compelling glimpse at what a multicultural (not to mention multicivilizational) utopian future might look like. Perhaps more importantly, this movie takes a franchise that’s seemingly indelibly stamped with the scarlet letter of geekdom and gives it mass appeal. —Michael Saba

56. Logan’s Run (1976)

Director: Michael Anderson

In the far-flung future of 2274, 30 is the new 80. Unfortunately for those who think they’re entitled to a second act in life, like Logan 5 (Michael York), escaping can get you sentenced to “Deep Sleep” by the Gestapo-like Sandmen. And even if you make it past the human assassins, you could still wind up face-to-chrome grill with Box, the magnificently melodramatic robot who ran out of fish! And plankton! And sea greens! And protein from the sea!, and so decided it might as well flash-freeze some fresh Runners instead. I can’t prove it, but I have a sneaking suspicion Billy West modeled his performance of thespian robot Calculon from Futurama after Roscoe Lee Browne’s positively Shakespearean Box. “My birds! My birds! My birds!! —Scott Wold

55. Men in Black (1997)

Director: Barry Sonnenfeld

Tommy Lee Jones and Will Smith have tremendous chemistry in what’s essentially a buddy cop movie. But if the cocky, young cop starts out sure of himself, Jones’s Agent K quickly brings him down to an alien-infested Earth. Delightful in tone, director Barry Sonnenfeld plays into all our wildest conspiracy dreams, turning our everyday world into a secret refuge for an imaginative variety of creatures from planets beyond. The plot might be a little slim, but the alien vignettes along the way are clever enough to carry the weight. —Josh Jackson

54. Minority Report (2002)

Director: Steven Spielberg

The more we become connected, the more any sense of personal privacy completely evaporates. So goes Steven Spielberg’s vision for our near future, couched in the signifiers of a neo-noir, mostly because the veil of safety and security has been—today, in 2002 and for decades to come—irrevocably ripped from our eyes. What we see (and everything we don’t) becomes the stuff of life and death in this shadowed thriller, based on a Philip K. Dick story, about a pre-crime cop John Anderton (Tom Cruise) whose loyalty and dedication to his job can’t save him from meaner bureaucratic forces. Screenwriters Scott Frank and Jon Cohen’s plot clicks faultlessly into place, buoyed by breathtaking action setpieces—metallic tracking spiders ticking and swarming across a decrepit apartment floor to find Anderton, the man submerged in an ice-cold bathtub with his eyes recently switched out via black market surgery, immediately lurches to mind—but most impressive is Spielberg’s sophistication, unafraid of the bleak tidings his film prophecies even as it feigns a storybook ending. —Dom Sinacola

53. Videodrome (1985)

Director: David Cronenberg

Videodrome wears many skins: It’s a near-future thriller about the lines between man and machine blurring, a sadomasochistic fantasy, a chronicle of one man’s tragic descent into madness and even a screed against society’s abusive relationship with theatrical violence. Yet, more than any dermis it claims as its own, Videodrome is horror down to its bones, a shard of phantasmagorical mania wielded by the genre’s most cerebral master. The mind is where Cronenberg creeps, taking his imagination’s darkest wanderings—steeped in symbolism and subconscious detritus—to visceral extremes. The same could be said for smut peddler Max Renn (the always sweaty James Woods), manager of a cable TV channel devoted to finding new boundary-breaking entertainment, who stumbles upon a pirated broadcast signal carrying “Videodrome,” a seemingly unsimulated series filled with graphic torture and death. As Cronenberg’s dark dreams tend to do, “Videodrome” begins to warp Renn’s reality—our mind’s eye, as one episode explains to him, is the television screen—and the malevolent forces behind “Videodrome” convince him to go on a killing spree, armed with his newly grown mutant cyborg hand (which might be a hallucination but probably isn’t). Throughout, Cronenberg literalizes Renn’s grossest thoughts, opening up a vaginal orifice in his stomach (into which he salaciously sticks his handgun) or transforming his television set into a pulsating, veined organ, manifesting each apocalyptic vision with immediate, tactile reality. In Videodrome, maybe more saliently than in any of his other films, Cronenberg squeezes the ordeals of the slumbering mind like toothpaste from the tube into the disgusting light of day, unable to push them back in. Long live the new flesh—because the old can no longer hold us together. —Dom Sinacola

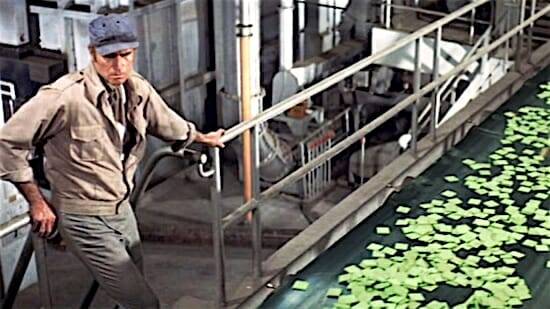

52. Soylent Green (1973)

Director: Richard Fleischer

Cannibalism is usually such an intimate affair. Not so in Soylent Green, a loose adaptation of Harry Harrison’s 1966 novel, Make Room! Make Room!, in which “Soylent Green is people!” Along with his famous call for cleaner, less groping ape hands, Charlton Heston’s delivery of Soylent Green’s signature line has proven one of his most lasting contributions to pop culture, as well as one of the great spoilers of film history. —Michael Burgin

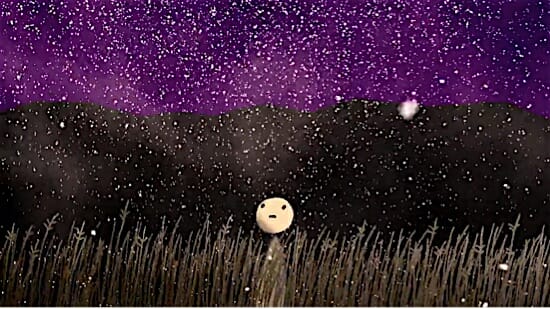

51. World of Tomorrow and World of Tomorrow – Episode Two: The Burden of Other People’s Thoughts (2015; 2017)

Director: Don Hertzfeldt

In the first part, in 16 minutes, Don Hertzfeldt lays out humanity’s destiny: a vastly interconnected age of barely functional connections. In stick figures, impressionistic smatterings of vibrant color, geometric arrays, a snippet of a Strauss opera and the perspective of one little girl, Emily (Winona Mae), World of Tomorrow makes all science fiction to come before feel limited, not far-reaching enough—not enough. In 16 minutes. In any of the subjects that keep us up at night, that define us through our calamities—mental degradation, the loss of memory, nostalgia, cloning, AI, robotics, time travel, immortality, death, the incomparable loneliness of the universe—in Hertzfeldt’s deceptively simple animation, all is boiled down to an essence, a “yes” or “no” question: Why does simply being human push us farther and farther away from each other? Further and further away from ourselves? In the case of Future Emily falling in love with a mining robot, Hertzfeldt doesn’t want us to take it seriously so much as feel the pain, any pain, of Emily inevitably abandoning the robot to its long, blank eternity without her. In the case of hundreds of thousands of botched time travel missions killing time travelers by stranding them in an unknown time, or, worse, depositing them into the thinnest outer reaches of our atmosphere so their bodies fall back to earth, a beautiful nighttime show of falling stars, Hertzfeldt expects you to find this all pretty funny, because he knows you are using laughter to bury the urge to scream hopelessly into the indifferent void about just how meaningless your existence truly is. In 16 minutes: All of this—including a moment that will make your heart skip a beat because, in 15 minutes, you’ve become irrevocably attached to this little girl, Emily Prime, and you can’t bear the thought of leaving her, this little stick person cartoon, to face the universe alone.

Episode 2, a headier, longer (22 minutes) and altogether more ambitious continuation of the first film’s story of the endlessly replicating entity beginning with Emily Prime, revolves around a realization, uttered by Emily-6, a clone of the clone Emily Prime met in the first film: “If there is a soul, it is equal in all living things.” Emily-6 is more vessel, more of a vestigial being, than individual human, created as a backup for Emily’s memories, and so serving no functional purpose. She once again travels to the past to walk with Emily Prime, this time through Emily-6’s own psyche, hoping Emily Prime will be able to offer some context, some meaning, for everything she’s storing. At once, Hertzfeldt captures that disorienting distance between our memories and our sensation of inhabiting them, a distance that only grows wider and weirder with time, to the point that we may even doubt their veracity. And yet, these memories are the key to our immortality. Are our memories what make us human? What make our souls? Revisiting a moment in Emily’s life in which she kills a bug, realizing that bug is dead, no clones to replace it, just gone forever, Emily-6 grasps the futility of her own design. If there is a soul, she has one different from Emily Prime, different from the version of Emily upon which she’s based. The empathy of this moment, as is the case with so much of what Hertzfeldt’s accomplished in barely half an hour, is heart wrenching. —Dom Sinacola

50. Paprika (2006)

Director: Satoshi Kon