Designing The French Dispatch: An Interview with Production Designer Adam Stockhausen

Photos Courtesy of Adam Stockhausen

Adam Stockhausen has placed a large and perhaps indelible stamp on the films of Wes Anderson. For many years, cleverness, quirkiness, personality, insight, humor and emotional nakedness were their cornerstones, and strong ones: Trademarks, components of a brand, points of auteurism in its purest sense. When Stockhausen came along, starting with Moonrise Kingdom, it was as if those elements found an adhesive medium that blended them into an entirely different product—still recognizable as an Anderson film but also radiating something just south of what Walter Benjamin would have called an “aura.” A presence that leapt beyond the facts of the story, shaping your experience of the film and haunting you afterwards; the consciousness of deliberation, the presence of a fervent visual mind with energy carefully applied.

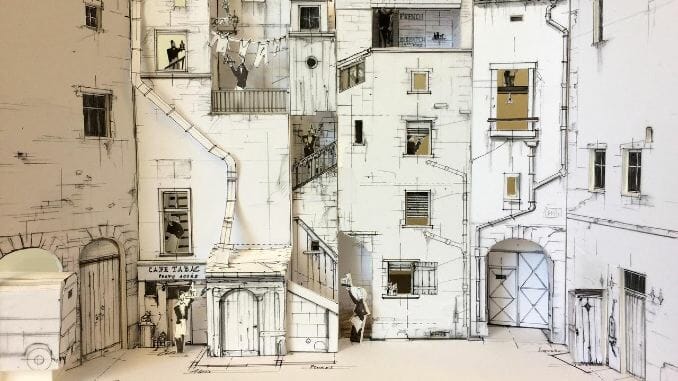

So it is with The French Dispatch, Anderson’s latest, a story about the Paris bureau of a Midwestern newspaper that looks and feels a lot like The New Yorker. The very structure of the film—interrelated news stories, all with a touch of redactive how-would-THAT-ever-happen absurdity—lends itself to the kind of detailed and productively obsessive work that is Stockhausen’s m.o. Paste talked to Stockhausen about the impossibilities, hurdles and joys of designing The French Dispatch.

Paste: I’m curious about the importance of repetition in your work, what it grew out of, and what feeling you’re trying to create with it, specifically?

Adam Stockhausen: Well, it’s a very interesting question. And I hate to be disappointing but it’s kind of something that we don’t, or I don’t, think about so actively. I think it’s just second nature, as well as the fact that what Wes likes, I gravitate to automatically. Something starts to crop up when we’ll be scouting, and we’ll go to wherever we go. In Grand Budapest we’d be scouting and you would see these coal-burning heaters in the corners of all these rooms. And you just start to see it over and over and over, and then you start to say, “Well, that’s a good idea. That really is part of the feeling of this place, right?” And so then you start to use that over and over again, because that’s what you saw when you were scouting. In Moonrise Kingdom, raccoons kept finding their way in. On The French Dispatch, this kind of yellow color kept finding its way in. And so, it happens gradually.

Do you ever discuss the effect on the viewer of the repetition? In The French Dispatch the effect of seeing all these doors and identical elements gives a feeling of complexity or of a certain amount of unpredictability. What’s behind all these doors?

Stockhausen: Well, when you’re describing that, I’m thinking about the police station and how the confusing nature of the police station is part of what it is. We were putting doors everywhere to try to make the place as confusing as possible, because it is a maze that he walks through trying to find his way to the dinner. I mean, even when we made the big corridor where Jeffrey’s walking and trying to find the place, we were using mirror tricks, putting a mirror at the end of the corridor to try to make it look like it went on forever and definitely making it as confusing as possible, because that’s what he’s going through as a character.

I have a really technical question. It may seem like a naïve question, but it’s something that occurred to me while I was watching the film. A lot of it is in grayscale. Does that affect your choices as a production designer in terms of the props you use or the colors you use before the film is actually put in the process? And does that change the way that you view what you’re choosing to film or what you’re choosing to place in the production design?

Stockhausen: On this one, Wes was making those decisions about which parts were going to be in black-and-white and which parts were going to be in color as we were developing, as we were in prep and as we were getting close to filming, and he was on the fence about a couple of different areas in the film. So we went at it in a few different ways.

In “The Concrete Masterpiece,” for instance, we knew that we were going to see those spaces in color and in black-and-white. So that in a way that was the trickiest, because we had to evaluate: How will this read in a grayscale? But it also had to be pleasing visually in color. And so that involved a lot of having your iPhone on the black-and-white setting: Looking at it with our eyes, but also looking at it through this handy little filter we all carried around in our pockets. Some colors do different things, of course, in black-and-white and so it was tricky to get the right balance and the right effect to happen simultaneously in color and in black-and-white: The tones of the wood and the floor in the hobby room, the exact level of the distressing of the walls in the hobby room, the way the sunlight and shadow were working in the prison itself. We were looking at all of that simultaneously. Other sections, like the police station, we knew that was going to be in black-and-white. We occasionally even did sets entirely in black-and-white with paint. We didn’t actually use color because we wanted to reinforce what the ultimate look was going to be for the actors on the set.

I read that you had 130 different sets for this film. Based on the fact that things were changing so much, and there’s so much complexity in the storytelling, how did you keep track of all those sets?

Stockhausen: It was kind of nuts. The way we shot it helped, shooting the stories as stories. In a normal movie, scenes will be all jumbled up and you’ll be shooting the bits from the middle, bits from the end, and bits of the beginning. In this one, each of the stories was shot as a contained piece. We did those pieces sprinkled throughout interstitially. In between the stories we would do three of the Sazerac pieces or four of the Sazerac pieces, and then we would launch into another one of the main stories.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-