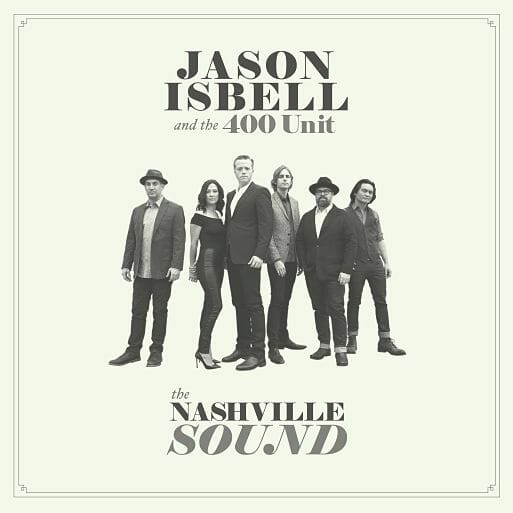

Jason Isbell & the 400 Unit: The Nashville Sound

Jason Isbell is often cited as being one of the best songwriters in the world. That sort of expectation can be a challenge to live up to, but for some reason Isbell continues to sally forth, upping the ante in all aspects of his craft. His new record The Nashville Sound, his first with the 400 Unit since 2011’s Here We Rest, is triumphant in its topical resonance, but draws influence from the timelessness of lyrical curiosity. Whether delivering heart-wrenching lines on the crumbling of the American Dream, or the crumbling of a relationship, each is given an equal shake, and that makes his songs unreasonably powerful.

“Last of My Kind” recalls the melodic cadence of the Dead’s “Friend of the Devil,” though Isbell’s demons arrive in the form of big city isolation, the reminiscence of bygone years and cognizance of the galloping hooves of mortality. The sparse acoustic number is an interesting choice as album intro, given that The Nashville Sound is Isbell’s first non-solo record in a while. Its doubling as an indictment of metropolitan homelessness, and the futility of looking back, gives its starkness more gravity, as Isbell mournfully notes, “Daddy said the river would always lead me home/but the river can’t take me back in time/and Daddy’s dead and gone.”

The vestiges of Isbell’s solo ambiance on the opening track is pounded back on the “Keep On Rockin’ in the Free World” abandon of “Cumberland Gap,” the first song to showcase the 400 Unit’s riotous rock ‘n’ roll combustion. The tune paints a despondent tale of being caught in an alcoholic tailspin in the shadow of the Appalachian Mountains, where the coal mines have dried up, and “there’s nothing here but churches, bars, and grocery stores.” It’s vivid commentary on the overlooked populace of boom towns in decline, and an animal of a rock song on par with the best of Ryan Adams’ more churning efforts.

Read our in-depth interview with Jason Isbell here.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-