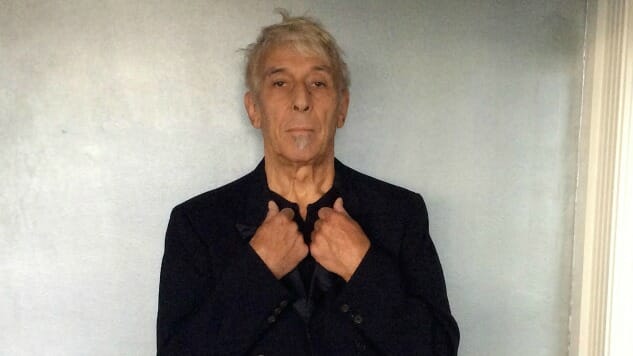

John Cale on “Hallelujah”: “There’s Something About Everybody in a Leonard Cohen Song”

Photo by Abby Portner

It’s hard to know where to start when considering John Cale. Practiced in a whole spectrum of genres, the 74-year-old Welsh composer, singer, songwriter and producer began his long, storied career in New York in the ‘60s alongside Lou Reed in art-rock pioneers The Velvet Underground. He likewise helped produce iconic works like Patti Smith’s Horses (1975), The Stooges’ self-titled debut (1969) and Nico’s The Marble Index (1969). Cale has also led an incomparable solo career, the highlights of which are captured on his 1992 live album, Fragments of a Rainy Season, which he reissued via Double Six/Domino Records earlier this month.

Among the live record’s many gems is Cale’s piano-only rendition of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” which he famously included on the 1991 tribute album I’m Your Fan and reformatted to only comprise its cheeky verses (i.e., no biblical references). There’s also his booming 1973 anthem “Paris 1919,” the 1975 ballad “I Keep a Close Watch” and his and Reed’s 1992 homage to Andy Warhol, “Style it Takes.”

Cale hopped on the phone with Paste to delve further into his latest reissue and its revered track list, plus expound on why he’s glad he rearranged Cohen’s “Hallelujah” the way he did.

Paste: What led you to reissue this particular live record?

John Cale: I [reissued] Music For a New Society, and that was because it hadn’t been available for a while and people were asking at gigs and all that. I knew there were a lot of tapes I hadn’t listened to. And a lot of performances.

For Fragments, I set out to make a live recording, and I made sure that every concert we did in Europe (I think there were eight of them), we organized the recording every day. We’d drive around in the truck and set up and make sure that we could grab everything and make everything accessible. We made the setlist the same every night, so you knew where it was on the tape. But then there were all these other things that happened: There were solo performances all over the place, in Melbourne and in Wales. I haven’t listened to any of that.

What we had was this small Steinway that we travelled with—this funny little crane that France had made for the space program. We took the piano off the truck, rolled it onto the crane and wheeled it into the gig and put it up on the stage and then assembled it. It was a Steinway, but it was sharp. So everywhere else we went, in the other tapes when I went to them, there were these nine-foot grands, and they sounded tremendous.

Paste: So Fragments’ minimalist arrangement wasn’t intentional from the start?

Cale: No, the idea was about the songs. It was a focus on how you present the songs. I have some solo guitar stuff there. But the piano, what I wanted to do was to focus on the perfect thing in the song and who the character was this time with the song. It changed every night. Some nights he would be angry, sometimes singing—he’d be funny about it. It really was about mood and how do you change the mood of the song. So I was doing it just to see what kind of situations came up. Different emotions and moods.

Paste: Right, it does place so much more of a focus on the singer’s voice and its nuances.

Cale: Yeah, it gives you more control, too. I mean, you can push the performance in several different directions.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-