Mars 2020: Take a Peek at the New Martian Rover

We’ve sent quite few rovers to Mars. From Pathfinder (which had a second life in pop culture thanks to the book/movie The Martian) to Opportunity to Curiosity, the United States has sent a grand total of nine landers to the red planet. And now, we’re prepping another rover: Mars 2020, scheduled to launch in (you guessed it) the year 2020.

Why do we need another rover, though? It’s a fair question. We’ve already sent so many unmanned landers to the red planet; why send another instead of going ourselves?

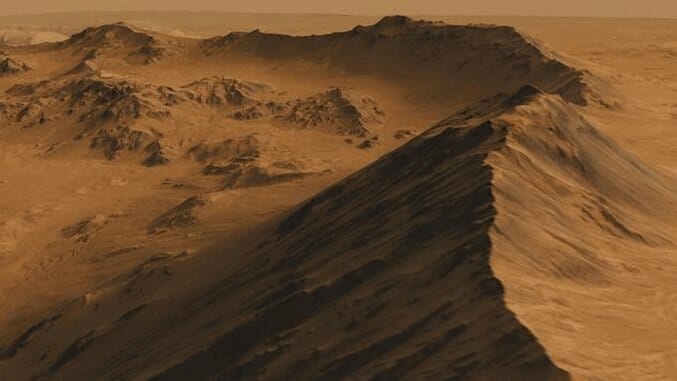

Sunset on Mars (Image credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona)

Sunset on Mars (Image credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona)

![]()

The answer is precisely because we’re going to go ourselves. Mars is not close to Earth; it’s not like going to the Moon, where if something goes wrong, it’s a mere three-day journey home. Mars is nine months away, at its closest (and that only happens once every 26 months or so). We need to know what’s in store for our astronauts. If they’ll eventually live and work on the red planet, what can they expect? Where are good landing sites? What areas should they avoid? What is the soil made of; can we find fuel or water underneath Mars’ surface? The only way to prepare for a human visit to Mars is to gather as much data as possible, which means sending another lander.

As of right now, Mars 2020 has three different possible landing sites: the Jezero Crater, which is a dry lakebed that may have once harbored life, NE Syrtis Major, which used to be warmed by underground volcanic activity and, perhaps the most interesting for those of us interested in a manned mission to Mars, Gusev Crater. This was also the landing site for the Spirit rover. While it may seem like a waste to send a rover somewhere we’ve already been, there’s some logic behind it. First, Mars 2020’s instruments are going to be much more advanced than Spirit’s, so there will absolutely be the opportunity to build on what we’ve previously learned and ask new questions based on data we already have. Second (and this is especially interesting for those of us invested in humans going to Mars), because we’ve mapped part of the Gusev Crater, this would provide a second look at the site as a possible landing destination for astronauts.

Mars 2020 artist’s concept (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Mars 2020 artist’s concept (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Curiosity takes a self-portrait on Mars (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

Curiosity takes a self-portrait on Mars (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)