Escape The Summer Heat In Bryce Canyon Country

Photos from Unsplash

It was August in Texas, and fatigue had set in from seeing triple-digit numbers taunt me from the weather forecast every day for the last few months. A notification arrived in my inbox with an invite to Bryce Canyon Country in Utah. I quickly looked up the temperature forecast and was pleased to see two numbers where there had previously been three. Even better, the first number was a five. Sold.

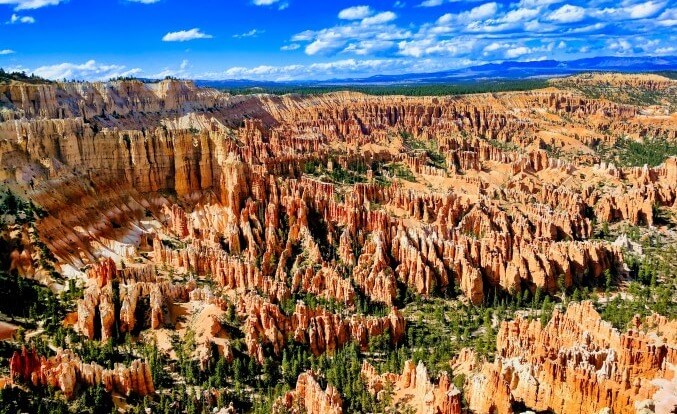

Of course, escapes from the annual summer inferno are hardly the only reason to visit Bryce Canyon Country. Alien-looking rock formations, honky tonks, live country music, slot canyons, rock climbing, astonishing sunsets, secluded hikes, and incredible silence are also yours to discover in this spectacular stretch of the desert. Bryce Canyon Country occupies a stretch of southern Utah that is so isolated and sparsely populated that until the mid-19th century, local maps of the area were essentially a giant question mark. The Henry Mountains, the last mountain range in the United States to receive a name, are located here, and the explorers who did ultimately map the terrain deemed the countryside so rugged that “no animal without wings should ever cross.” If you’re looking for a place to truly immerse yourself in the wonder of the wilderness without worrying about crowds or lines, then you can’t do better than Bryce Canyon Country.

Given the isolation, it should come as no surprise that there is no simple way to get here. I arrived in Salt Lake City, and after meeting my group at the airport, we all piled into a shuttle provided by Southwest Adventure Tours and commenced the four-hour drive south down I-15 toward the park. I found myself getting pulled into the mystique of this slice of Utah as hints of the city began to fade into endless trees and wild peaks while we learned some backstory behind the name “Grand Staircase.”

The Grand Staircase is a series of cliffs that span vast stretches of Utah and Arizona, beginning with the Grand Canyon, the first of the “steps.” Many of these steps form part of famous parks—from the top of the Grand Canyon, the staircase ascends and leads to the bottom of Zion National Park. The upper tier of Zion then leads to the beginnings of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and from here, the climb continues to the bottom of Bryce Canyon National Park, whose cliffs then form the top of the staircase.

We arrived in the sleepy town of Escalante at sunset, grabbing a tasty burger in the inviting, casual atmosphere of the 4th West Pub. Afterward, we headed to the Canyon Country Lodge, a cozy little hotel that also doubles as a great place to base in-depth trips of the region. The night would pass quickly—we awoke at 6 a.m. the next day for our first canyoneering adventure.

We met Rick at the offices of Excursions of Escalante, a gregarious and endlessly quotable local whose love for the Grand Staircase had transformed itself into a tour company over the last quarter-century. Rick was the very best kind of guide one could ask for on a trip like this; his knowledge of the area was unmatched, and some of the group’s reticence towards canyoneering was quickly put at ease with his warmth, humor, and emphasis on safety. His passion for the Grand Staircase was infectious to the point of setting the tone of inspiring teamwork and the very best of everyone on the trip, regardless of experience level. “I have canyons for everyone,” he said as we received our backpacks and walked out back for the safety demo.

We found a small table filled with esoteric gadgets, varying in complexity from electronic handheld radios to long pieces of rope. After picking up the walkie-talkie and giving us some phone numbers for emergency services, he turned into what he claimed was the most important gadget of the trip—the satellite G.P.S. radio. He showed us how, with one flick of a button, anywhere in the world, stranded travelers could summon help. It didn’t take much to motivate us—the next words spoken were, “You’re the most important person in the world to somebody out there, and this can save your life.”

Ultimately, we learned that the most essential and versatile tool would be ourselves. Everyone would have a role according to height and size—tall, short, heavy, light—everyone had a part to play, whether scouting, rappelling work, or rope setup. As the tallest member of the group, I learned that I was the “dipstick,” and my role would be measuring water depth if need be or using myself as a baseline for fitting into the various nooks we’d be encountering. The “meat”—typically the lightest person in the group—would act as a human anchor for jobs requiring tethering and rappelling. As Rick explained these roles, he approached me, foot extended, with the instructions to “please step on my foot.” I reluctantly obliged, and he repeated the exercise with the rest of the group, demonstrating how to use ourselves to create makeshift holds and balance points for each other. “The best canyoneers aren’t the ones with the most, best, or fanciest equipment; they’re the ones always pushing, pulling, and using one another as leverage,” Rick noted. After we all took turns flattening Rick’s poor foot, we piled into the vehicles that would take us to our loadout point.

We went down a few county routes, passing Grand Sheffield Road, an excellent camping spot for adventures into the canyon. We arrived at a clearing where we hopped out of the trucks and into the silence and awe-inspiring sights of the Grand Staircase. We grabbed our backpacks, and before beginning our descent, we did a quick “circle of trust,” touching knuckles in the middle before breaking with a “Let’s go to work!”

The walls came with various holds, mainly taking the form of cracks, roots, or trees. As we used these and others to begin our initial descent, the utility of the foot flattening tutorial became apparent as we pressed and pulled on one another to maneuver safely down the rocks with minimal holds. Each level we accomplished seemed to reveal new depths to be explored, and we learned that using the body as leverage was just the bare surface of the techniques needed to traverse the walls. Each canyon was less of a physical challenge than a mental puzzle to be analyzed and solved using these tools at our disposal; it was simply a matter of working out the best path, using our assigned roles and strengths to our advantage, and then working together to conquer obstacles. Among other tricks, I learned the “foot bridge”—using my feet as a literal bridge to straddle small openings in the rocks, or the “body bridge”—literally bracing myself with hands and feet across two surfaces and then moving across gaps one limb at a time like Spider-Man. At times, we were invited to “donate some fabric”—coming to a seat and sliding down butt-first in our hiking pants down steeper rock faces where applicable.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-