Leaving Neverland Isn’t Michael Jackson’s Story, and That’s As It Should Be

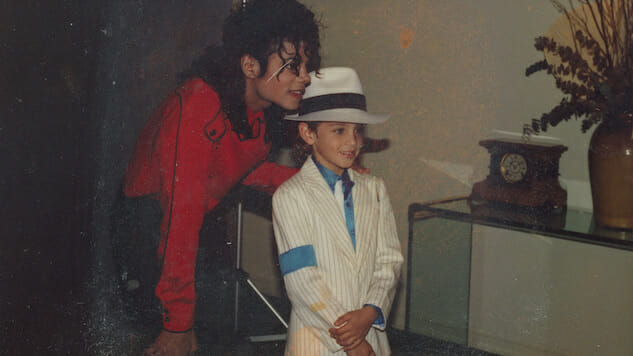

Photo: HBO

It’s all heartbreaking. The damage to the psyches of children, certainly, but everything else is sad as hell, too: the endless voracious need for approval at any cost, the radioactive half-life of a lie, the emptiness at the center of fame, the way child abuse is a perpetual motion machine that infects one generation after another. In an oblique way, HBO’s Leaving Neverland is a reminder that the monstrous people who sexually abuse children do not simply drop out of the skies. They are forged. Created. Usually by abusers of their own. You look at Michael Jackson—his collapsing, bleaching face; his skinny little body; his soft, mealy speaking voice—and you can see a victimizer who was also a victim. If we could hold that perception and really understand it, would it change anything? The desire to withhold forgiveness from such people is deep and tenacious, and it’s more than understandable why that’s the case. No one tests the limits of forgiveness quite like someone who has molested children.

Wade Robson met Michael Jackson at age five, after winning concert tickets in a Michael Jackson dance competition in Brisbane, Australia. James Safechuck was a Simi Valley kid whose folks had gotten him into commercial acting¬—he was cast as the boy who brings a Pepsi to Jackson’s dressing room and becomes seduced by the glittery jackets and dark shades. Both men still clearly recall the intoxicating sense of unreality associated with being in Jackson’s orbit. The words “overwhelming,” “otherworldly” and “impossible” come up a lot. So does the word “God.” As they tell their chillingly similar stories, the urge to dwell on what had happened to Jackson, what had made him whatever he was, is methodically stripped away. He goes from being a charismatic weirdo who was obviously in a world of pain and seemingly did some awful things to being an alarmingly canny Pied Piper who knowingly put everyone around him into a nasty, nasty little trance to conceal something bordering on inhuman. He used his fame and money and influence to seduce young boys, and indeed their entire families.

The four hours of Leaving Neverland are characterized by a cavernous sense of aural and visual space. The sound editing is almost uncomfortably intimate; I squirmed at the audible swallowing and breathing sounds in the interview segments. There’s also the way archival photo images are centered deeply in the frames—small, surrounded by black space, static. It’s elliptical, allusive. And effective. The testimony of the two alleged victims (and their mothers and their wives) is uncontested, and they do not affirmatively prove anything, but their stories strike so many of the same chords that you’d have to be awfully spaced out not to notice. The seduction of the boys’ star-struck and ambitious mothers. (Wade Robson’s mom relocated him from Australia to Hollywood, splitting up her family on the promise of Jackson’s mentorship and help.) The extended, extensive grooming process. Manipulative generosity. (A passage where James Safechuck describes Michael taking him to a jeweler to buy him a ring is especially creepy; apparently, Jackson had an elaborate story that James was helping him select something for a woman friend, and the kid’s delicate little fingers were the right size.) Creating a shared secret. (“No one can find out about us or we’ll both go to jail!”) Escalating physical contact, and escalating de-emphasis of the boys’ families. (Both men report Jackson having insinuated early and often that women, including mothers, were not trustworthy.) Replacing them with new boys and suddenly not being that interested in paying for their apartment or bringing them to Neverland for the week. On and on. Tellingly, both men—especially Safechuck—not only acknowledge their earlier denials of the molestation, but still use descriptors like “in love” and “we were like a married couple.” They describe jealousy and hurt, not relief, when Jackson began to favor, say, Macaulay Culkin. Mercifully, it is beyond my purview to determine whether these men’s stories are “true,” but I will say they definitely don’t come across as vengeful, or venal.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-