This Is the Water and This Is the Well: Notes on Twin Peaks: The Return at the Halfway Mark

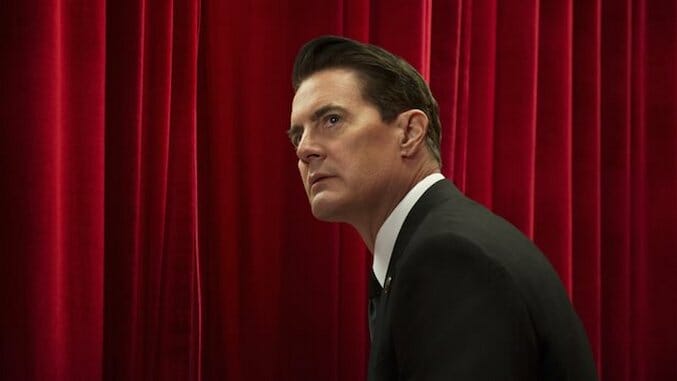

Photo: Suzanne Tenner/SHOWTIME

Twin Peaks is midway through its third season, and how lucky we are to be alive. Behold, I show you a mystery: In 1991, a television show sets a bar. Twenty-five years pass, its imitators rise, the world moves on. And then the show returns, comes out of retirement. And it beats the old record. Twin Peaks in the summer of 2017 is just as astonishing and groundbreaking as it was when it detonated in the American mindscape back in April 1990. It has lost none of its power to move, mold and disturb in the quarter century since. We are nine episodes deep into those dark forests. May we be lost in them forever.

The show seems to have a long-lasting, unbreakable accord with the television medium. Twin Peaks does what it wants, like a leviathan whale churning up the bottomless ocean: It moves as it wills, and every other program swims in its wake.

The reviewer owes two duties to the reader: critical faculty and a readable account. I dislike reviews that incorporate the writer’s biography. Larding a review with too much of your own story is a capital crime of the critical business. But with this show, the personal element interferes. This story vibrates the bones, and to make an honest assessment of the show requires an amount of personal confession. I thought it was boring, and the way was lost. I have never been so happy to be wrong. Lynch and Frost have done it again.

A Place Both Wonderful and Strange

Where to start with Twin Peaks? If we were walking down the street, here’s what I’d tell you: David Lynch is a visual artist who became an immensely popular avant-garde director back in the 1980s. His films were unapologetically surrealist and popular. He makes a series of world-beating films: Eraserhead and Blue Velvet are merely the most famous. Then Lynch teams up with veteran showrunner Mark Frost and crafts Twin Peaks, which is the first professionally strange serial-mystery event TV, ever. A homecoming queen is mysteriously killed in a small logging town near the Canadian border. A young FBI agent is sent to investigate. There are paranormal elements. Those are the bare boundaries: Everything and nothing happens within them. Twin Peaks is a detective story the same way Hamlet is a comedy about stepfathers.

Seeing Twin Peaks when it first came out was like watching the early episodes of Seinfeld. The reigning emotion was not amazement, but confusion: What the fine hell is this? The show was so good, in every single way, that Lynch made the cover of TIME on October 1, 1990. Meanwhile, everybody in America watched this show. Like penicillin or The Simpsons in their heyday, Peaks was loved by everyone: soap opera buffs and starlets, intellectuals and indie kids. That was the first season.

During the second year, Lynch left to go film Wild at Heart. The suits interfered. The show declined in ratings. Cancellation followed. A movie came out, called Fire Walk With Me. It’s great, but nobody thought so at the time. The gang behind the series went their separate ways. Every TV producer and writer in America took notes, and all the children of Lynch-Frost follow: The X-Files and Lost, Northern Exposure and Picket Fences, The Sopranos and Riverdale.

Twin Peaks became immortal: the show everybody knows. Untouchable. The standard for thinking, artistic television. Like new philosophy or old industrial chemicals, its influence is broad but not obvious. You can see its tracks everywhere. Stylistically, Twin Peaks seeped into the ground, changed the world. It’s a kind of entertainment Copernicus: We stand on a shifted earth. Dave Chappelle said on Inside the Actors Studio that “the mark of greatness is when everything before you is obsolete, and everything after you bears your mark.”

And then, one fine day in October 2014, Lynch and Frost announced that the show was coming back. A universal freak-out followed. Including yours truly. It was the appropriate response.

When You See Me Again, It Won’t Be Me

Three years passed. May 21, 2017 arrived, and The Return was on. The first four episodes moved with warm-lizard speed, which was to say, not at all. There was little music and the shots went long. Dale Cooper, our hero, was locked in the extra-dimensional Lodge. The scene shifted to a mysterious warehouse in New York where a lonely man watched a glass box, before getting assaulted. Strange happenings abounded in South Dakota, where Cooper’s doppelgänger—Bad Dale, or Doop, to use the Internet’s phrase—had been running around murdering and criming up America for the last quarter-century. The Log Lady made an appearance. A headless body was found, and the narrative crept on.

None of this description, by the way, provides a full accounting of the slow sureness of the story. I cannot give a whole representation of the series, any more than I could gift you Niagara by pouring a stream of clear water into a cold glass. Nor can I paint for you the emotional tenor of the moments I spent at my friend Ann’s house, leaning forward on her futon to stare into a laptop screen: When do we get Dale, my hero, back? The next several episodes kept up with the glacial steps: Doop murders some more, James Hurley shows up at the Roadhouse. Dale Cooper flees the Lodge and spills out into space. Eventually Cooper makes it back to our world in the identity of Dougie Jones, a hapless insurance executive who barely talks. And so while Doop kept plotting and causing mayhem, and the FBI got wind of the events in the Midwest, Dale Cooper was trapped as a shambling, barely-speaking protagonist.

It stabbed at the soul. Where was my beloved small town? Had I waited a quarter century to see my protagonist rendered into silence? Keep in mind, my generation had its heart broken by the Star Wars prequels. Lucas once considered hiring Lynch to direct Return of the Jedi, and it seemed like Lynch and Lucas had met in a single point. This relaunch of Twin Peaks was another cruel joke: He was going to make us all like Dougie Jones, confused, hapless, trapped in a monotonous hell while watching the hollow promise of the show we had waited for wilt. Lynch spent minutes of each episode having a band play a musical interlude. It seems like a high note on the auteur “Fuck you” scale. It agonized. I quit watching. I had a text thread with friends and Twin Peaks superfans Todd Gray (who was once arrested for copying one of Cooper’s monologues to his answering machine) and Rob Bass (who took part of his honeymoon in locations where the series was shot).

I told them I decided to back off from The Return. They disagreed with me. Twin Peaks is still the weird little town we all loved, Todd argued, but “it’s now the most normal fucking place in America with Bad Dale having spent 25 years on a rampage across the U.S.” The world was now full of prestige TV, Rob wrote, but “this new business that’s already aired, for me, just as effectively smashes all of that other shit to pieces every bit as much as the original absolutely laid waste to the surrounding landscape at the time.”

I missed the human interaction of it. I wanted to love the show. Was this our reward for waiting a quarter of a century? Ben and Jerry, Lucy, Hawk, and Andy seemed diminished to the point of irrelevance. Where, really, was the pompadoured maestro leading us? What dark hills did he expect us to journey to? What did South Dakota mean? What about that mystery box in New York? And what of the Black Lodge raw madness, and the grim spectacle of Doppelgänger Dale monstering up and down the dark backwoods of America? Not to mentioned Our Favorite Agent in a stuporific fugue state. I wanted nothing to do with it. But my friends kept the faith. “Come back,” they would tell me. “This is Lynch. This is Peaks. You remember how you loved it so.” They got me to return for Episode Seven.

And then. And then. The color poured back into the show.

It all came back together for me; the music came back, and by the time Dougie wrestled the gun away from the mystery assassin, I felt like I was watching Twin Peaks. Is there a single moment when I came back? Maybe when they read Laura’s diary again—Laura, always saving everyone in her town, and us the audience, too. Maybe it was the face of Andy, surrounded by synthesizer music and tall trees. Or maybe it was my friends, who believed all the way.

Give Yourself a Present

Rob wrote:

You go back to that friend’s house. You maintain that relationship. At the expense of all others… The Good Dale is waking up. The Bad Dale is on the highway. Garmonbozia is all around us, humming through the overtone of the high A you get when you lick your index finger and start doing laps around the top of a glass of red wine. Music is returning to the air, slowly but surely.

It all clicked for me. By the time “Part VIII” crossed my screen, I was back in. I stayed during the half hour of flashback. Your reviewer was rapt when our narrative shifted to New Mexico in 1945, and Lynch gifted us with the world-breaking thunderhead of the Trinity Bomb Test, with its sonic halo of radioactive atmosphere bursting through the speakers and mutant fish crawling on the ground and into rooms. I watched when the Fusco Brothers, detectives all, took down the Spike and Johnny Horne ran his head into a wall. And when the final destiny of the Family Briggs was revealed, everything I’d wanted came true.

Lynch was worth waiting for. This show was worth waiting for.

After two seasons, a movie, a book, and nine new episodes of Twin Peaks, here is what I have learned: Almost every professional commenter gets Twin Peaks wrong. They misjudge it as dour, they think Lynch is ironic, they use potted phrases to miscategorize the show. But the fans are right, and always have been.

I think Lynch’s version of the world is carnivalesque: He is beguiled by the world’s strangeness. The critics think Lynch’s lesson is “Everything is superficially beautiful with evil underneath.” No. Lynch is a prophet of a different faith. Lynch’s teaching is that the Earth is complicated. The world is good, but is filled with the inexplicable: Heroes can have strange desires and complicated histories. Twin Peaks is the rock that breaks camp: It proves that great works of art can float free of category. Not everything we love must be divided into simple spheres of “serious” and “comic.” Life is strange, and the art that represents it ought to share in its oddity. That is why I love this show: it seems a truer accounting of the world than anything I ever saw on Nightline or The Wire or Mad Men.

This is the value of David Lynch, and Mark Frost, and the series they have created. Mystifying, exasperating, patience-whittling Twin Peaks: my anchor, my candle. Your sprawl pine-needle saga paid off. I thought Lynch was Ahab, but he was Treebeard: longwinded and trying to help. Sticking with an artist is an emotional business. The British Prime Minister Disraeli wrote: “When one is young [one] chooses one’s poet and abides by him.” Lynch is a strange landlord, but has never cheated on a lease; he has inspired by his making, and will, I trust, never give a marring. Even two and half decades later. I am eager to see what follows: Twin Peaks has me for as long as it runs. The gum I liked is coming back in style, but it never went out. It is happening again—but then again, it always was.

Twin Peaks: The Return airs Sundays at 9 p.m. on Showtime.