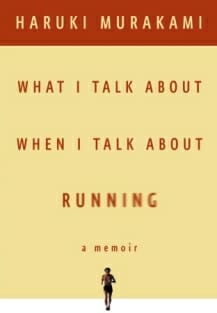

Haruki Murakami

Japanese fiction master gets personal

“What do you jot down about jogging?” late comedian Bill Hicks sneered about deceased health writer Jim Fixx. “Right foot, left foot—faster, faster, umm, go home, shower.” As if in direct response (or, more likely, in tribute to Raymond Carver), Haruki Murakami has written the new memoir What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. As it turns out, there’s quite a lot to say.

Murakami’s first explicitly autobiographical work, Running demonstrates the kind of willful economy necessary for a marathon. Nearing 60, the Japanese novelist has much to mine from his life—jazz, food, American culture, even childhood—so there’s no need to blow it all out at once, as the long-distance writer would be the first to tell you. Like many of his novels’ narrators, Murakami is diminutive and quick to point out his normality. But, also like his narrators, he is utterly unique. Writing about himself through the filter of other topics suits him well.

In Running, Murakami uses a right-foot/left-foot pace to access the same peace his previous fictional characters found between trips down mysterious wells and interactions with sheepmen. “What exactly do I think about when I’m running? I don’t have a clue,” Murakami insists. But that’s not true. His writing is effortless, open.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-