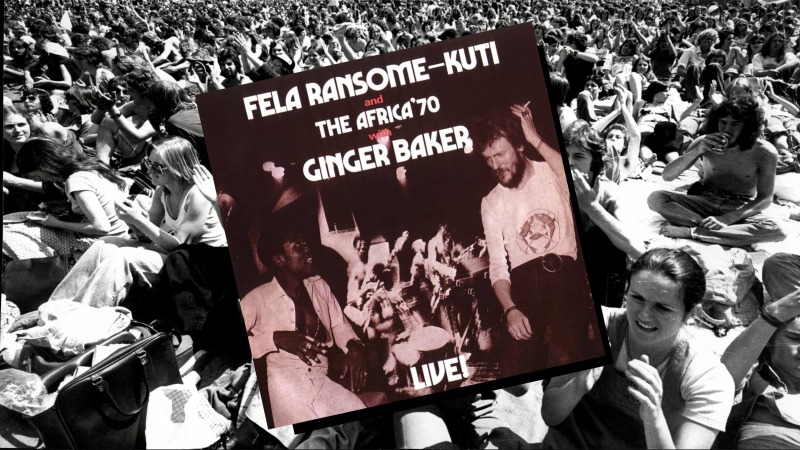

Time Capsule: Fela Kuti and The Africa ‘70 with Ginger Baker, Live!

While the album helped launch Fela Kuti’s career in Europe and elsewhere, assisted, in part, by the crossover attention given to Baker and Kuti’s collaboration by the English press, the real star of this recording session is the Africa ‘70.

In late July 1971, on an unseasonably cold London day, a 12-piece band from Lagos, Nigeria arrived at Abbey Road Studios for two recording sessions. The band was called the Africa ‘70, and they were helmed by their bandleader, legendary musician and political activist, Fela Kuti. Even in 1971, Kuti was a giant figure in Nigerian culture and music. He and the Africa ‘70 had plans to record two albums in these two days. The first album, tracked on July 24, became Afrodisiac The second recording was to be a live album, recorded before an audience. It would feature Cream’s drummer and longtime friend of Kuti, Ginger Baker. Known as “rock’s first superstar of drumming,” he befriended Kuti several years earlier, around the time that Cream broke up, in 1968. Just four months after this July recording session, Baker would journey to Africa to set up a recording studio with Kuti in Lagos, as documented in the 1971 film, Ginger Baker in Africa. This second album became Live! and was released just one month later, in August. It would become one of the most acclaimed live albums of all time.

The recording sessions were a big deal for both Kuti and EMI, the label that owned Abbey Road Studios. Kuti was the first signing to EMI’s Africa imprint, and Live! would be the first major international release of Afrobeat—a genre Kuti had created that combined elements of jazz, funk, salsa, calypso, and Yoruba, the indigenous music of Nigeria. He and his band had tried to break into the Anglophonic market before. They recorded the ‘69 Los Angeles Sessions a couple of years prior, while they were playing six nights a week at actor Bernie Hamilton’s nightclub, Citadel de Haiti, on Sunset Boulevard.

But that album, recorded in haste, after the American authorities realized Kuti and his band had overstayed their visas, and it wouldn’t see proper international distribution until a reissue in 2010. And EMI didn’t release either of his 1970 albums internationally, just through their Nigerian imprint. So, in other words, Live! was the first real taste that European and American audiences had of Kuti’s music (likely thanks, in part, to Baker’s appeal to pop and rock-leaning crowds). It therefore could be considered the first Afrobeat album released outside of Nigeria, one that found second lifetimes in the hands of DJs generations later, recontextualizing Kuti’s material as afro-pop and groove’s rightful precursor.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-