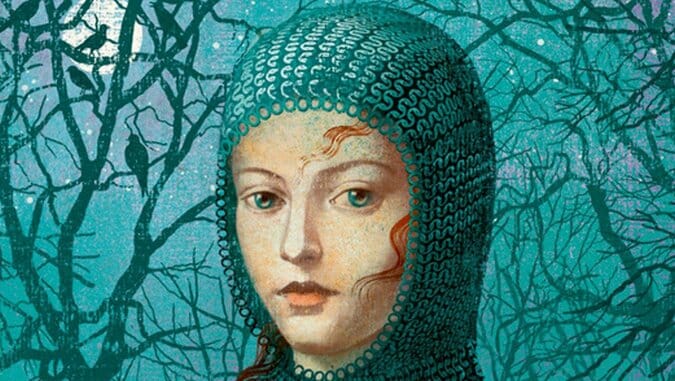

Hild by Nicola Griffith

Looking Forward to the Past

A little girl carries a heavy gold cup filled with mead through a hall packed with eager guests. Normally it’s a grown woman’s job. Today a precocious child bears the ceremonial chalice.

Enormous fire pits blaze at the center of the room, and the ceilings vault high above the crowd. Men fill lines of benches. Tapestries hang from stone walls. A king waits, bedecked with heavy gold and jewels. Rich cloth glitters in the firelight. The music of a lyre amplifies the dramatic moment.

The king drinks from the giant cup, then to his honored guests.

A man leans down, tells the girl she’s strange. “I am the light of the world,” she says. She repeats what her mother dreamt before the girl’s birth: You are Hild, the light that will shine on all the world. The king’s niece. His shrewd new prophetess.

Don’t let the cover of Nicola Griffith’s newest novel fool you. You won’t find the typical medieval girl-in-a-dress novel. You’ll read something completely different, otherworldly in its scope and beauty.

Set in seventh-century England and based loosely on what little knowledge exists about the early life of Saint Hilda of Whitby, Hild earns a place on the shelf beside masterful historical-fiction works such as Hillary Mantel’s Man Booker Prize-winning novels of Thomas Cromwell, Wolf Hall and Bringing Up the Bodies (set some 900 years after Hild). All these novels boast finely spun characters and accomplish what is most fascinating in historical fiction: They display a common thread of humanity before an intricately detailed backdrop of times long past.

In Hild, Roman roads crisscross the countryside. Fearsome sprites lurk in woods and water, and strange priests of the new god Christ, wearing long black skirts, roam the damp English countryside. Like salesmen, they promise regional kings victory in battle and many healthy sons if they simply renounce their pagan gods and accept baptism.

We meet Hild as a toddler. Her father rules over a portion of England, until a rival poisons him. Hild’s maternal uncle, also a king, takes in the family, initiating the course of Hild’s uncommon life.

Her frequently unscrupulous and always cunning mother teaches Hild to watch people keenly. (“Always know what they want to hear—not just what everyone knew they wanted to hear but what they didn’t even dare name to themselves. Show them the pattern. Give them permission to do what they wanted all along.”) Her mother also shows her how to deliver observations to the king with a prophetic flair, then this ultimate stage mom convinces the king of Hild’s visionary power.

Hild has little choice in the path her life takes. She quickly becomes indispensable to the king, traveling with him around the country, predicting the weather days in advance, warning him of distant cousins scheming to overthrow him. Her prophecies always come true.

The people around her assume a supernatural source for Hild’s many visions, but in truth the predictions spring from keen and persistent scrutiny of every tiny piece of the world she inhabits, from the behavior of birds and insects to the maneuvering of political adversaries: “Hild looked deeper, letting her mind sink into the glimmer and shadow, as she might in the wood, looking at the leaves, or lying on her back watching the clouds, letting the thoughts come, letting the things she already knew arrange themselves in a pattern, a story that others might call a prophecy.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-