The Good, the Bad and the Ugly at 50

Half a century later, cinema is still awestruck by Leone’s “fairy tale for grown-ups”

“This is what the Western does—it releases you… And more important—it releases the characters. They can be more primitive; they can be more Greek, like Oedipus Rex or Antigone, you see, because you are dealing again in a sweeping legend.”

—Anthony Mann

“The desert settings appear to stretch at least as far as the orbit of the planet Neptune. And the barrel of each gun looks to be roughly as large as the Holland Tunnel. … What I wanted even more than the setting was that feeling of epic size.”

—Stephen King, on viewing The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

The beginning of Man of Steel (2013) opens on the alien planet Krypton as Russell Crowe races to be with his pregnant wife. He flies on the back of some kind of creature, I think. (It’s been three years.) Things explode all around him. Some pursuing jet fighter (or something) shoots at him. All hell is breaking loose. The world is literally coming to an end. Really, though, he’s trying to get to his pregnant wife. There is so much stuff happening, but not a whole lot going on. If there’s a reason so many cinephiles still laud Italian director Sergio Leone’s “Spaghetti” Western films, we might start there in explaining it.

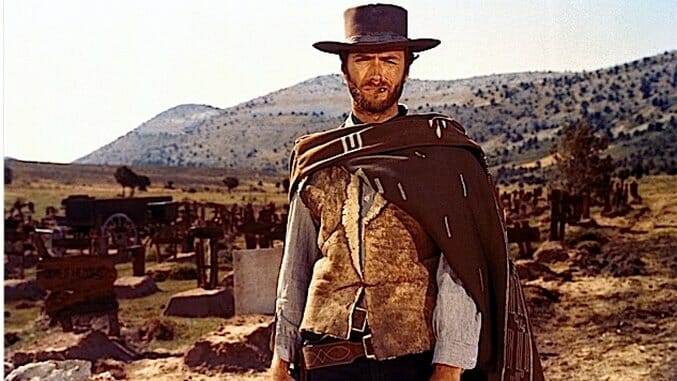

Because despite a lack of exploding cities or armies of computer-generated robots or stunning reveals of parentage, without a post-credit teaser tying it to the same “cinematic universe” as the Lone Ranger, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly feels grander and more mythic than contemporary movies about actual mythic characters. It’s redundant at this point to say that it’s the platonic ideal of the Spaghetti Western. It would appear to be entirely composed of silly Western tropes (ridiculously exact marksmanship, the jangly music cues that insinuate themselves into the scene, the hero in a battered poncho) if not for the fact that it fathered them.

I submit that it isn’t a film audiences today would respond well to: The pace is meandering, the plot contains a few holes that require the sort of mental fill-ins that are completely forbidden by today’s scriptwriters, and there are long stretches of seething, brooding silence where not a lot happens (but a great deal is going on). The violence seems quaint.

Yet, like the fatalistic samurai epics and acidic noir that gave birth to it, director Sergio Leone’s closing entry in the unofficial Man With No Name Trilogy remade the badass cinema landscape.

“John Wayne once wrote me a letter telling me he didn’t like High Plains Drifter. He said it wasn’t about the people who really pioneered the West. I realized that there’s two different generations, and he wouldn’t understand what I was doing. High Plains Drifter was meant to be a fable.” —Clint Eastwood

The Western had fallen on hard times when Sergio Leone and other directors like Fred Zinnemann (High Noon), Budd Boetticher (Seven Men From Now), and Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch) came along in the ’50s and ’60s to turn it into a drier, crueler genre. The cowboy B-movies of the ’30s and ’40s had become too expensive to make and yielded too little returns in an age when television was rising and cinema attendance falling.

The term “Spaghetti” Western was slapped on Leone’s three landmark films (For a Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and finally, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) as something of an insult because of how obviously they had been produced in Europe with Italian actors. For his own part, Leone argued that it was perfectly reasonable a foreign filmmaker chose to make his mark on such an American genre.

“Several great directors of Westerns came from Europe: Ford is Irish, Zinnemann Austrian, Wyler is from Alsace; Tourneur, French. I don’t see why an Italian should not be added to the bunch,” Christopher Frayling quotes him as saying in Once Upon A Time In Italy.

Leone, the son of a film director and an actress who spent his childhood in Rome under Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship, took some of his inspiration from John Ford’s films, which ranged from bygone classics like 1939’s Stagecoach to John Wayne vehicles like The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. which used the actor’s aging eminence solely to add a layer of tarnish to it (much as Clint Eastwood would do in Unforgiven and Gran Torino).

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-