What Is Truth? Two Books Explore the Deadly Silence and Lies of the Emmett Till Trial

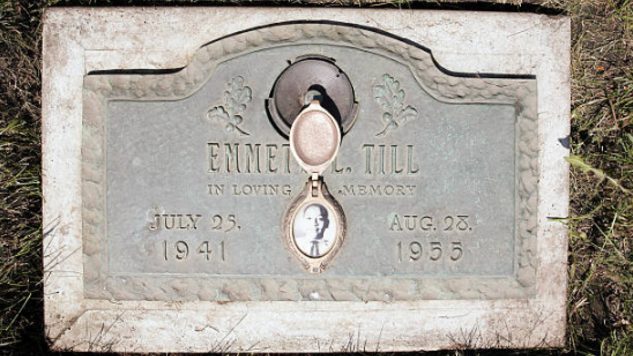

Photo by Scott Olson / Getty Images

Over six decades have passed since Emmett Till, a black 14-year old from Chicago, was kidnapped and killed in a gruesome lynching in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi. Yet his death, his killers’ acquittal and the subsequent wave of protests—marking the beginning of what we now call the Civil Rights Movement—continue to impact American culture.

In recent years, the deaths of Trayvon Martin (2012) and Michael Brown (2014) have led to the nationwide mobilizations of Black Lives Matter and a renewed focus on racism in America. Thousands of protesters have invoked Emmett Till’s name and legacy as they marched in cities across the nation, showing that the past’s ugly truths are never far from sight.

Two recently released books examine the Till trial in light of what we now know. The Blood of Emmett Till by Timothy Tyson and Writing to Save a Life by John Edgar Wideman highlight slavery’s crooked legacy by plumbing the perspectives of two seemingly marginal figures who weighed on the course of justice in 1955. Silence is the key binding these two characters together, but their fates reveal as much about America’s history of racist violence—and a lack of justice—as the trial itself.

![]()

Days after Emmett Till* was roused from bed in the dead of night and bundled into a car by two white men, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, his body turned up in the Tallahatchie River, badly mutilated and with a heavy cotton gin fan tied around his neck. The ensuing trial set off a media firestorm thanks to the efforts of Emmett’s mother, Mamie. Her brave decision to have an open casket funeral in Chicago—”Let the people see what they did to my boy”—and to attend the trial drew swarms of reporters to Sumner, Mississippi that fall.

But an unusual thing happened at the trial. After the prosecution, having provided eyewitnesses not only to the abduction but also to Emmett’s torture, rested its case, the defense called Carolyn Bryant* to the witness stand. Carolyn, Roy’s wife, had been working in her family’s store when Emmett, accompanied by a cousin, had done or said something to provoke her. Witnesses for the prosecution testified that J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant had later set off in a car looking for the “one that done the talking.” But the defense spent most of the trial claiming that their clients had done no such thing; they even questioned whether the body found in the Tallahatchie was Emmett’s.

Carolyn’s decision to testify on behalf of the defense was a bizarre twist, as the defense appeared to be offering a motive for a crime they were claiming had not been committed. Making matters even stranger, writes Tyson in The Blood of Emmett Till, was that “the prosecution wanted to stop the defense from explaining why their clients were guilty.”

But for those attuned to the Jim Crow South’s perverse logic and criminal justice system, both requests made perfect sense. The defense was claiming that the murder victim had tried to sexually assault a white woman, the wife of one of his killers. And the prosecution was trying to prevent the jury from hearing this justification. As long as Carolyn sat on the witness stand, it was Emmett who would be on trial—for having violated Mississippi’s racial codes, for having provoked his own death.

The judge sent the jury out of the room during Carolyn’s testimony, but it didn’t matter. When she told the courtroom that Emmett had grabbed her arms and waist and had spoken lasciviously to her before fleeing, she provided those present with the racist excuse needed to condone a racist murder. And so they did—the all-white jury voted to acquit after just an hour of deliberation.

As the fallout from the killers’ acquittal spread around the country and the world, a narrative emerged that Emmett had, as Tyson explains the thinking, “been at the wrong place at the wrong time [making] the wrong choices.” Even Emmett’s own mother said in countless interviews that her son, Chicago born and raised, was unaware of the South’s racist customs, which dictated the “proper” conduct between a young black boy and a white woman. Emmett was portrayed as a victim of his own ignorance, not the malice of others.

Embarrassment and outrage over the acquittal—which led to nationwide protests and worldwide condemnation—led Mississippi to assemble a grand jury to indict the killers on kidnapping charges. But justice would be perverted again. Emmett’s father, Louis,* was “conjured like an evil black rabbit from an evil white hat,” writes Wideman in Writing to Save a Life, his book that blends memoir, history and fictional speculation to probe the details of Louis’ life.

Information from Louis Till’s confidential army service file was leaked to the press: [he] was not the brave soldier portrayed in Northern newspapers during the Sumner [Mississippi] trial who had sacrificed his life in defense of his country. Private Louis Till’s file revealed he had been hanged July 2, 1945, by the U.S. Army for committing rape and murder in Italy.

The Mississippi grand jury declined to indict the killers on kidnapping charges. Louis’ execution, Wideman writes, “erased the possibility that [Emmett’s] killers would be punished for any crime, whatsoever.”

![]()

Timothy Tyson, a white southern-born historian, was invited to interview Carolyn Bryant after her daughter read his 2004 book Blood Done Sign My Name, a memoir of a 1970 North Carolina lynching and its aftermath. As the two sat in her living room in 2008, drinking coffee and eating pound cake, Carolyn revealed something appalling to Tyson: “About her testimony that Till had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities, she now told me, ‘That part’s not true.’” This remarkable admission, offered up decades after the trial and its aftermath shook the nation and galvanized the Civil Rights Movement, chilled Tyson.

Timothy Tyson, a white southern-born historian, was invited to interview Carolyn Bryant after her daughter read his 2004 book Blood Done Sign My Name, a memoir of a 1970 North Carolina lynching and its aftermath. As the two sat in her living room in 2008, drinking coffee and eating pound cake, Carolyn revealed something appalling to Tyson: “About her testimony that Till had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities, she now told me, ‘That part’s not true.’” This remarkable admission, offered up decades after the trial and its aftermath shook the nation and galvanized the Civil Rights Movement, chilled Tyson.

If that part was not true, I asked, what did happen that evening decades earlier? “I want to tell you,” she said. “Honestly, I just don’t remember. It was fifty years ago. You tell these stories for so long that they seem true, but that part is not true.”

This revelation—buttressed by what Carolyn told her own lawyer in the days after the murder—is what drove Tyson to write The Blood of Emmett Till. The book provides a painstaking recreation of the murder and the trial while also foregrounding the social context. The book’s best moments come when Tyson dissects the ways in which white supremacy was reinforced at every level of the state and society, puncturing the pieties of those white people—Carolyn Bryant and Tyson’s own family included—who believe they, and their ancestors, were free of racial bias. His attention to detail also resurrects the largely invisible roots of black resistance and consciousness to the World War I era, while also pointing out ways in which slavery and its legacy still casts an ugly shadow today.

![]()

John Edgar Wideman, a black MacArthur Fellowship-winning novelist and essayist, has produced something more experimental in Writing to Save a Life. The text combines speculative passages with diaristic asides and archival research, a collage that seeks to understand Louis Till, a man barely present in the historical record yet whose absence speaks volumes. In recalling a man who was prevented from speaking—who was executed and later dredged up to block justice for his murdered son—Wideman asks hard questions of the often-invisible power of white supremacy.

John Edgar Wideman, a black MacArthur Fellowship-winning novelist and essayist, has produced something more experimental in Writing to Save a Life. The text combines speculative passages with diaristic asides and archival research, a collage that seeks to understand Louis Till, a man barely present in the historical record yet whose absence speaks volumes. In recalling a man who was prevented from speaking—who was executed and later dredged up to block justice for his murdered son—Wideman asks hard questions of the often-invisible power of white supremacy.

Louis was, by every indication, a violent man given to angry outbursts. “According to Mrs. Till, Louis was often brutal with her. Put his hands on her. Then absent. Then dead,” Wideman writes. But Wideman, using the liberties afforded novelists within a book categorized as “nonfiction,” goes beyond the archive, imagining what Louis might have been like during his short life. Wideman never justifies Louis’ violence, but pairing it with Wideman’s own memories of growing up under a despotic father in the ‘40s results in a dazzling—and devastating—display.

Without straying far from Emmett’s murder and trial, Writing to Save a Life’s narrative revolves around another racially charged trial, the one that convicted and executed Louis. In 1945, Louis and two fellow black soldiers had been accused of entering the home of an Italian family in the town where they were stationed, raping two women and then killing a third in the house next door. But the court martial record of the trial, the same one leaked to the press in 1955 during the trial for Emmett’s kidnapping, is full of “conflicting, ambiguous hearsay evidence that for some reason defense lawyers…allowed to stand.” The case against Louis, Wideman concludes, was powered by the same ineluctable logic that would kill his son 10 years later.

Colored soldiers whom the army considered second-class citizens were suspects who possessed no rights investigators need respect. The logic of southern lynch law prevailed. All colored males are guilty of desiring to rape white women, so any colored soldier the agents hanged could not be innocent.

During the investigation into the crimes, an investigator, posing as a fellow prisoner, tried to ease a confession out of Louis. Though his co-conspirators were “busy accusing one another,” Louis remained silent, until finally remarking, “There’s no use in me telling you one lie and then getting up in court and telling another one.” For Wideman, this quip—Louis’ only direct quote in the historical record—constitutes Louis’ “resignation, his Old World, ironic sense of humor about truth’s status in a universe where all truths are equal until power chooses one truth to serve its needs.”

![]()

There is a clear resonance between Louis’ assertion on the nature of truth and Carolyn’s recognition that a story told enough times “seems true.” In the context of a courtroom, where participants are asked to swear to tell “nothing but the whole truth,” Louis (who said nothing in his defense) and Carolyn (who lied) both appeared to acquiesce to the same truth: murder as an appropriate response to black sexuality.

Wideman refuses to plumb Louis’ motives, explain away what happened or offer up some form of forgiveness to the man. Nor does Tyson speculate as to what Carolyn did or didn’t know, leaving the question of her culpability for Emmett’s death and his killers’ acquittal in another’s hands. (Both offer compelling theories, but they refrain from ultimate judgment.) What’s left is a discomfiting revelation of how often memories crumble along the fault line of race—and how often those distorted messages pass into the historical record. Instead of taking stories we think we know at face value, both books illuminate the moral urgency of asking difficult questions of the past—even when what we fear most is the answer that might come back.

*For clarity, Emmett Till is referred to as “Emmett,” Louis Till is referred to as “Louis” and Carolyn Bryant is referred to as “Carolyn” in this article.