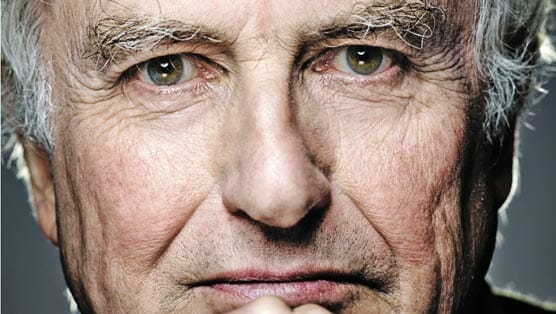

Brief Candle In The Dark: My Life In Science by Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins has a signature style, or as Neil DeGrasse Tyson put it, “a method.”

The Director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York called Dawkins out for this method, as is documented in one of the more particularly interesting portions of the newest memoir covering the British evolutionary biologist’s “Life In Science,” titled Brief Candle in the Dark. Dawkins had just delivered a talk criticizing a “religiously-inclined ecologist” when, afterward, Tyson gave some constructive criticism. He implored Dawkins to consider that “there’s got to be an act of persuasion” where education’s concerned, and it needs to be more nuanced than the professorial punch of “here’s the facts, you are either an idiot or you’re not.”

The Director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York called Dawkins out for this method, as is documented in one of the more particularly interesting portions of the newest memoir covering the British evolutionary biologist’s “Life In Science,” titled Brief Candle in the Dark. Dawkins had just delivered a talk criticizing a “religiously-inclined ecologist” when, afterward, Tyson gave some constructive criticism. He implored Dawkins to consider that “there’s got to be an act of persuasion” where education’s concerned, and it needs to be more nuanced than the professorial punch of “here’s the facts, you are either an idiot or you’re not.”

“The facts plus the sensitivity,” Tyson said, is what “creates impact.”

Dawkins, who served as professor of public understanding at the University of Oxford, is famous for his campaign as an “evangelical atheist” advocating for a “non-theist” or “secularist” intellectuality—or, rather, a naturalistic view of the world. Many of you likely read his famous books on evolution like The Selfish Gene (in which he introduced the word “meme” into our vernacular) or The Blind Watchmaker (an award-winning work from 1986 that argued against a divine creator). He would hammer non-theist points home in 2006 with The God Delusion. Since then, he has been considered as the ostensible figurehead for the advocacy of a “secularist” way of thinking and way of life. In other words, he often pisses off religious folks. But this book is more concerned with the development of a scientist, a diligent and thoughtful devotee of Darwinism, not an overt renegade divider of public opinion.

Tyson appraises Dawkins’ style as “articulately barbed.” Now, that would be all too apparent and a fair assessment to anyone who does a Youtube search on Dawkins after reading this review. But those more fiery sermons can be left to the enrage-able re-tweeters, because Brief Candle is a breath of fresh air in comparison. The book presents a much cooler, calmer recounting of his experiences in the field of scientific study, from his earlier days in academia inspired by the works of Darwin, to his days as a zoologist lecturing in animal behavior, later, as a published author and as the first professor to hold the Charles Simonyi Chair (as professor for public understanding). He even admits that he dislikes “the adversarial style of debating.” There are, of course, subtle barbs sutured throughout the pages of the book, as he may specifically be pricking any readers who hold an inkling of support in the notions of creationism. “…every time a scientist agrees to such a debate (with creationists) it creates an illusion of equal standing.”

In Candle, Dawkins admits a hope that the themes of his 12 books can be taken together as encompassing a biologist’s worldview. But, while dispelling religion has been a more expressed goal, a quieter (and more integral) goal of his, as he discusses in the chapter titled “Unweaving the Threads From a Scientist’s Loom” has been to present (or promote) this naturalistic view, informed by the studies of evolution and biology, with coherence. It’s the coherent presentation that is vital. Hence, “public understanding.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-