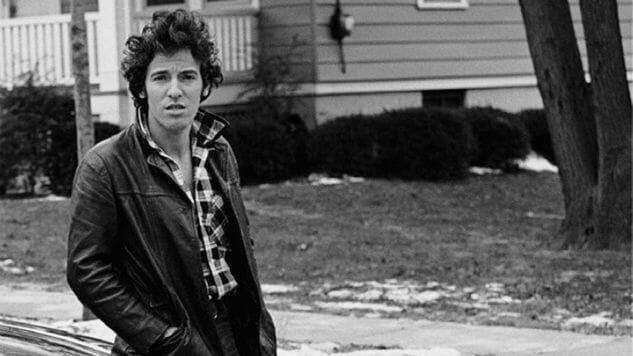

Bruce Springsteen Delivers a Rough Memoir in Born to Run

Born To Run, rock legend Bruce Springsteen’s new memoir, reveals its beating heart at the book’s midpoint. It’s there that we find our hero, flush with the success of his 1980 album The River and subsequent world tour, feeling lower than ever.

Springsteen embarks on a cross-country road trip with a friend, moving from New Jersey to California. At a stop in Texas, the precarious balance of his life comes crashing down as he watches people enjoying the delights of a small fair:

“From nowhere, a despair overcomes me. I feel an envy of these men and women and their late-summer ritual, the small pleasures that bind them and this town together… It’s here, in this little river town, that my life as an observer, an actor staying cautiously and safely out of the emotional fray…reveals its cost to me.”

Some version of this moment has likely played out in every platinum-selling, pop idol’s life. The nature of the music business is to suck talent dry without concern for an artist’s emotional and psychological wellbeing. But as Springsteen reveals throughout his messy and poignant book, his cultural prosperity weighs heavy on him.

Some version of this moment has likely played out in every platinum-selling, pop idol’s life. The nature of the music business is to suck talent dry without concern for an artist’s emotional and psychological wellbeing. But as Springsteen reveals throughout his messy and poignant book, his cultural prosperity weighs heavy on him.

He comes from hardscrabble roots, a working class family that barely scraped by led by an emotionally distant, hard-drinking father. Springsteen’s guilt over his artistic triumphs paired with the lack of love he received from his dad combined to produce some of the most explosive songs of the 20th century. But they are also elements of Springsteen’s life that he took great pains to avoid facing head on.

When he finally pulls back the curtain in Born To Run, it’s an electrifying read. What surrounds its molten core is layer upon layer of anecdotes tracking Springsteen’s journey to the mountaintop, relaying the inspiration and intention behind his most famous recordings—and occasionally diving too deeply into the murky waters of the music business. For fans, this is the perfect companion piece to the hundreds of books written about Springsteen’s life and work, adding extra shades of detail and illuminating moments that help further flesh out this iconic figure.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-