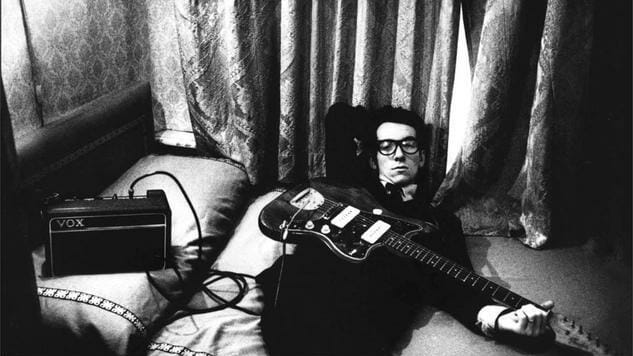

Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink by Elvis Costello

Across the nearly 700 pages of Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink, Elvis Costello delivers an impeccably detailed autobiography. He’s often as brilliant at turning a phrase in prose as he is in his lyrics.

The book opens with Costello’s boyhood memories of Saturday afternoons hanging around London’s Hammersmith Palais, where his father performed as a singer in the Joe Loss Orchestra. Costello and The Attractions played in the same venue, an overcrowded and overheated rock club years later, and area cabbies told Costello his father “was a better bloody singer than you’ll ever be.”

Costello explains that his passion centered entirely on music as a late teen, hardly a surprise for an only child whose parents met across the counter at a record shop. “Suddenly everything but music seemed like a waste of precious time,” he writes. But the knowledge of his father’s career—and the off-stage temptations that ultimately ruined his parents’ marriage—stood as more of a deterrent than anything: “For all that music meant to me, it still didn’t seem a likely or inviting occupation.”

Costello explains that his passion centered entirely on music as a late teen, hardly a surprise for an only child whose parents met across the counter at a record shop. “Suddenly everything but music seemed like a waste of precious time,” he writes. But the knowledge of his father’s career—and the off-stage temptations that ultimately ruined his parents’ marriage—stood as more of a deterrent than anything: “For all that music meant to me, it still didn’t seem a likely or inviting occupation.”

However unlikely or uninviting, Costello’s career in music took an ascendant arc that he neatly describes: his debut record My Aim Is True was cut in a total of 24 hours; its follow-up, This Year’s Model, took 11 days; his seventh album Imperial Bedroom was booked for 12 weeks of studio time, with famed Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick producing.

Costello first heard the Beatles when his father learned to sing “Please Please Me” by playing the single over and over. Soon, his father would share a bill on the Royal Command Performance with the Beatles, bringing their autographs back to his son. Unfaithful Music then jumps to 1999, when Costello is singing harmony with Paul McCartney at the tribute concert for his late wife, Linda McCartney.

That jump perfectly encapsulates the amazement and gratitude that shadow Costello’s recollections, sensations that never diminish despite his Hall of Fame credentials. “I know I never expected to meet half the people who I’ve encountered down these years and across these pages,” he writes in the final chapter. “I thought they were just names on record jackets, reputations spelled out in the light bulbs of a marquee, or consoling voices in the dark, but that’s not the way it has turned out.”

Costello’s reflective final passages aside, the book sparkles most during the pre-fame portion of his life. He looks fondly on his childhood, remembering family car trips to Spain and France and saving cereal box lids to get a Zorro sword. His first band was an imagined one, The Meteors, at seven years old, playing with cardboard guitars and wooden spoon drumsticks. Later, he’d spend hours at the “magnificent cave” of his local Liverpool record store, where he bought his first acoustic guitar on installment at age 14.

The writing that covers those years is full of wonder, and as his artistic identity begins to emerge, the reader is witness to the epiphanies that built upon each other to mold the Elvis Costello we now know.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-