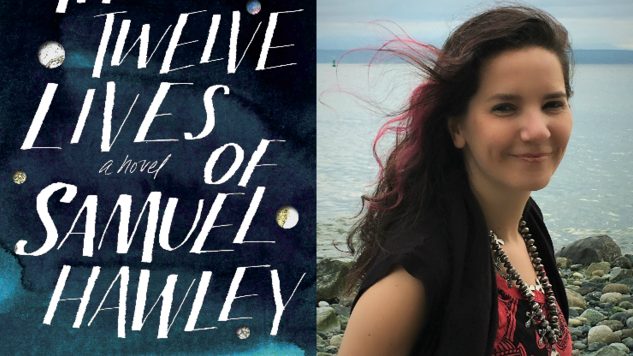

Hannah Tinti Tells a Story Through 12 Bullet Wounds in The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley

Author photo by Dani Shapiro

The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley, Hannah Tinti’s captivating second novel, weaves the saga of a father-daughter relationship through two narrative timelines. The first follows a young girl named Loo as she comes of age in a small Massachusetts town. The second reveals her father’s past through 12 stories explaining the events that led to the 12 bullet wounds on his body. A fascinating literary thriller, Twelve Lives gradually builds tension as both timelines count down to the final gunshot.

Paste caught up with Tinti to chat about the insane physical contest that inspired the novel, shooting guns for research, and Hercules’ influence on Samuel Hawley.

(This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.)

![]()

Paste: What sparked your idea for Twelve Lives?

Hannah Tinti: I was writing about the greasy pole; it’s a real contest that takes place every year in Gloucester, Massachusetts, which is near where I grew up. I was writing a scene about it, and I focused in on one of the men getting onto the pole. And as he took off his shirt in the scene—because a lot of the guys strip down to do this crazy, greasy pole run—I realized that his body had scars.

It got me thinking how our physical bodies are almost like maps of our lives and our pasts. When you’re with a new lover, for example, you’ll ask, “Where’d you get that scar?” And they’ll say, “This is when this happened to me.” Once I struck on this idea of skipping through time and telling a man’s life through his scars, I realized that each of those scars were bullet holes and the guy was a criminal. This ratcheted up the suspense-thriller element of the story and connected him to his daughter, who I came up with then I was deciding why the guy entered the [greasy pole] contest in the first place.

Paste: How long did it take you to write this novel?

Paste: How long did it take you to write this novel?

Tinti: From start to finish, including the editing time with my publishing, it was seven years. [My first novel] The Good Thief came out in 2008, and then I actually wrote about 200 pages of another novel, but it just wasn’t coming together. So I put it in a drawer before I struck upon this new idea. It took me about five years to write a draft of [Twelve Lives], and then I sold it. Then it took another two years to publish it.

Paste: Will you ever go back to the unfinished one?

Tinti: Who knows? Someday I’ll go back and look at those pages, but it was one of those things were I was writing because I felt like I should be writing. There was an anxiety built into it…There were other things going on in my life at the time. The book wasn’t going well; several members of my family got diagnosed with cancer. They’re okay now, and they’ve gone into remission. But there was the grind of being in the hospital all the time—dealing with medical care and the stress of possibly losing people you love. I went through a bad break up, and then I got in this car accident. I was okay, but it was one of those weird situations where you think, “What the fuck is going on in my life?”

That accident made me decide to drop the other novel. The thing I started pretty much right after the accident was Twelve Lives. It’s a powerful place to be writing from when you have nothing to lose.

So I started writing about what I knew. I’d just been to the greasy pole, so I wrote about the greasy pole. I’d been to Alaska, so I wrote about Alaska. I’ve been caught in a sandstorm in the middle of the Four Corners, so I wrote about that. I just started using things from my own life to build the story.

Paste: Guns play a large role in the novel. And when Hawley teaches Loo how to shoot, it felt real. Was that something you knew from your own life?

Tinti: I had absolutely no experience with guns before this book. I did do a lot of research, and I have friends who are in the military. This one amazing writer, Matthew Cheney, had inherited a gun shop. So he read an early draft of the manuscript to make sure I hadn’t made any glaring mistakes.

Paste: Have you still never shot a gun?

Tinti: I’ve shot tons of guns now, but I hadn’t before I started the book. There’s a shooting range in New York City in Chelsea—that’s the first place that I went. And then I had a friend who had an uncle that belonged to a gun range outside the city. I took the train out, and he brought all of his weapons and let me shoot every one of them—from sniper rifles to handguns to shotguns—so I could feel the difference between them. It was interesting for me to get to know those people, because that totally wasn’t my world. I was not raised around guns.

I think that sometimes in this country, there can be this real division between people who have guns and people who are against guns. Not that I think people should be carrying guns; frankly, I think if you have a gun, it ends up getting used. But it was interesting to get to know some very nice people with their own codes for weapons. I came to really respect them.

Paste: Something else that felt real was Loo’s nomadic existence as a child living on the run with Hawley. How do you get into the mind of someone trying to raise a child in those circumstances?

Tinti: That part wasn’t too hard. Kids can be raised in very strange circumstances, and they just think that’s the way it is. Did you ever have one of those moments where you’d go over to a friend’s house as a kid and think, “They’re weird too, but in a different way?” [Laughs] Every family has its secrets, and kids will accept anything.

For me, the main thing that [Twelve Lives] is about is the relationship between the two of them. And how our parents, when we’re growing up, are heroes and also strangers. As we get older and begin to find out new information about them, it starts explaining why they are the way they are. Our parents had lives before we showed up.

For us to find our own identities, we really have to understand our parents and where they’re coming from. That’s dialed up to 11 for Loo, because her father is a criminal. His secrets are bigger and his story is more mythic.

Paste: What were some of your favorite scenes to write in the novel?

Tinti: There were a lot of fun moments. I really enjoyed writing about the glacier calving in Alaska; I probably spent a week watching videos of glaciers calving. I had actually seen it in person, but if you ever want to go into a YouTube hole and not come out for a while, search “glacier calving.” These whole shelves of ice walls fall and—granted it’s terrible, because of global warming—it’s incredible with the giant waves of water.

Paste: Is there anything you’d like to add about the book?

Tinti: Hercules was actually one of the elements that helped me come up with the structure of the book. Once I knew that I was going to be writing about heroes and [Hawley’s] mythic energy, I reread the Greek myths. That’s how I came up with the number 12, because of the 12 Labors of Hercules. There are secret Easter eggs in the book that are nods to all 12 labors.