Maile Meloy Weaves Family Drama with Terror in Do Not Become Alarmed

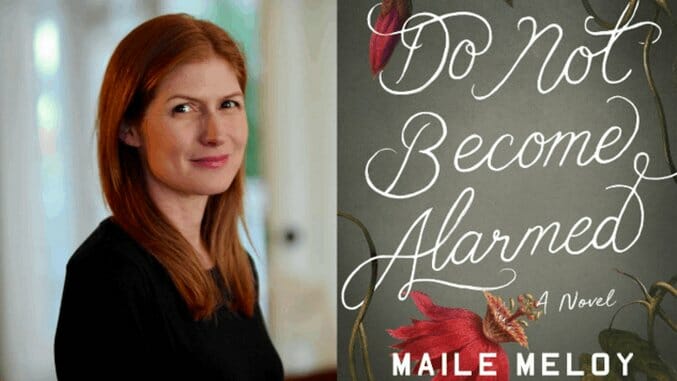

Author photo courtesy Maile Meloy

Editor’s Note: This piece is the Books Essential in Paste Quarterly #2, which you can preorder here, along with its accompanying vinyl Paste sampler.

Maile Meloy’s relentless new thriller, Do Not Become Alarmed, rushes through violence, self-loathing and recrimination as three couples contend with their children’s abduction during a cruise-ship vacation gone awry.

Meloy is best-known in literary circles for her taut New Yorker short fiction and as the author of two disarmingly incisive and funny family dramas: Liars and Saints, her debut novel, and A Family Daughter, the mind-bending sequel that recast Liars and Saints as fiction-within-fiction. She’s written the occasional spine-chilling short story, such as “The Girlfriend” (which prefigures the bereft-parents-blaming-themselves theme of Do Not Become Alarmed), but her latest novel raises the fear factor from anything she’s delivered to date in her fiction for adults.

However, Meloy’s three books prior to Do Not Become Alarmed, the middle-grade Apothecary series, were masterful slices of mystery, plausible Cold War espionage and narrowly averted nuclear catastrophe. The trilogy propelled Meloy to the forefront of middle-grade fiction, alongside her brother and sister-in-law, Colin Meloy and Carson Ellis, authors of the Wildwood series. The Apothecary books may prove little more than a busman’s holiday in the youth fiction realm for Meloy, but they demonstrate beyond question her talent for crafting high-tension fiction that compels readers to turn the page.

Do Not Become Alarmed begins not as a story of abduction but as a portrayal of the enduring yet nettlesome family ties that make Liars and Saints and A Family Daughter such unsettling reads. First cousins Liv and Nora, who grew up almost like sisters and continue to nurture their closeness and petty resentments as adults, agree to take their families on a cruise to Panama. On the third day of the cruise, both families (joined by a third family from Brazil) leave the ship for the first time. The husbands set off to play golf, and the wives, with six children in tow, choose a zip-lining excursion. After a series of mishaps, the mothers lose sight of the children, who are taken hostage by local drug traffickers.

Following the abduction, the narrative catapults back and forth between the children’s efforts to escape and their parents’ mounting anger at themselves and each other. The best elements of Meloy’s earlier novels—both youth and adult—emerge in these pages, between the imperiled children’s resourcefulness and their parents’ stored-up rancor that bubbles up throughout the crisis.

But the undercurrent of genuine terror that flows through Do Not Become Alarmed—the ever-looming fear that the kids won’t survive—is impossible to ignore in a way that isn’t present even in the Apothecary trilogy’s darkest moments. One never escapes the sense that these parents, whose perspectives dominate the book, will pay a steep price for their narcissism and that no timely deus ex machine will save their children. Unwritten rules of youth fiction, by contrast, would seem to preclude such dire outcomes. Kids in kids’ books can’t die (however close they might come), and the parents’ suffering is never portrayed with such the ugly human dimensions.

One of the most provocative passages in Do Not Become Alarmed suggests that Meloy has reflected on these different sets of rules, measuring the proximity of adult fiction to the harsh vulnerabilities of real life against the safer environs of middle-grade fiction. After years of project development for a Hollywood studio, Liv knows narrative conventions inside and out, and she has little tolerance for formulaic children’s stories. At one particularly bleak moment in the search for her kids, “woozy and confused, on a cocktail of adrenaline, Xanax, regret, leftover Ambien, and coffee,” Liv recalls the last book she read to her eight-year-old son Sebastian at bedtime:

They had started one of those wish-fulfillment kids’ adventure books, where the boy hero has exactly the qualities he needs to triumph, at every moment… She’d been bored and annoyed, and at one point she tried to explain to Sebastian why it wasn’t her favor-ite of his books. But Sebastian had loved the book unreservedly. Why hadn’t she just read the fucking thing with gusto and relished every moment with her son? Why had she brought her adult judgment and professional story opinions to a book her kid loved? Of course the child hero should always triumph! Who wanted a kids’ book to feel like real life? Real life was fucking intolerable.

After three middle-grade books that were easy to relish with gusto, it’s satisfying to find Meloy returning to long-form adult fiction as no less of a risk-taker than the Meloy of the Liars and Saints-upending A Family Daughter. But in Do Not Become Alarmed, she ventures into more frightening terrain in her most transfixing work yet. Real life is rarely so intolerable (one can hope) for most of Meloy’s readers as it becomes for Liv and Nora, but nearly all will find their real fears staring back at them from every post-abduction page.

Steve Nathans-Kelly is a writer and editor based in Ithaca, New York.