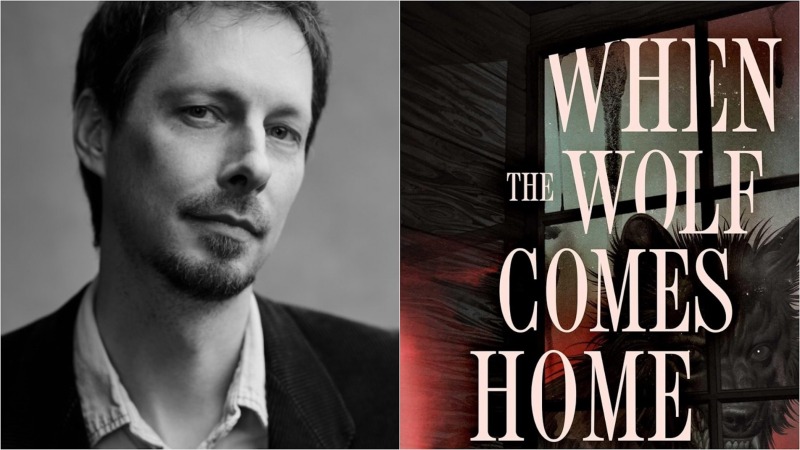

Nat Cassidy on Exploring the Monster of Fatherhood in When The Wolf Comes Home

(Photo: Kent Meister)

Over the last three years, Nat Cassidy has carved out a place as one of the most important new voices in horror, taking familiar concepts and hooks and weaving them into original, often devastating new stories like Mary: An Awakening of Terror and Nestlings.

Now, Cassidy returns with When The Wolf Comes Home, a horror novel that’s part werewolf story, part dark fantasy, part book-length chase, that again allows Cassidy to explore deep emotional connections while playing with familiar subgenres and structures.

Paste sat down with the author to discuss how When The Wolf Comes Home took shape, how fathers and fatherhood became crucial to the story, and what Cassidy found out about himself through writing this novel.

Paste Magazine: I want to start with the origins of When the Wolf Comes Home. Did it start out as, “I want to write a werewolf novel,” or did it start as, “I’m writing a novel about people with difficult relationships with their parents”?

Nat Cassidy: It started more on the latter, which is funny because that sounds like such a more mature story, and that was actually the story that I was drawn to write when I was like 13 and had the initial spark for this book. Readers of my first book, Mary, know that I also first attempted writing that book when I was 13, which sounds more impressive than it is because it was an unreadable little attempt at long-form storytelling that I was not ready to attempt quite yet.

But the book that I started writing after that, after I wrote that putative version of Mary, was this book that bears no resemblance to what this ultimate final version of it is, but it was about a little boy running away from an abusive father and the boy winds up under the care of this slacker, and then the two of them wind up on the run with the father pursuing them and cutting carnage through that slacker’s life trying to figure out where they’re going to go. That was the proto-version of me trying to wrap my mind around this story.

It really wasn’t until I started writing this version, this proper version a couple of years ago where I was like, “I wanted to tell a story about fathers and I wanted to tell a story about the complicated role that fathers tend to have in their children’s lives,” at least in my experience, and the kind of complicated role of fatherhood in general. And that got me thinking about, as it often does, monsters and manifestations and allegories and things like that and I just kept coming back to this idea of the archetypal disciplinarian, “Wait until your father gets home,” sort of authoritarian figure and the fear that figure can engender and how it kept just evoking the idea of shape-shifting to me, of a werewolf, of a huge hulking primal beast that strikes terror in something small and vulnerable.

It just became a story that was ripe for exploring not only the genre delights of that monster and the sort of story promises that having that monster in the fore can deliver, but the thematic ideas behind it, the resonances that we can explore, stripping that monster down to its bare essentials and seeing the humans underneath.

Paste: In the afterword to this book, you talk a lot about your own relationship with your father and how that inspired this story. Where did your adult protagonist, Jess, come from?

Cassidy: Jess comes a lot from me and a lot from my wife as well, from my wife’s relationship with father figures in her life.

I purposefully also wanted to have Jess represent not only a complicated father-child relationship, but this is a story specifically about fear and the different ways in which adults and children process fear and experience fear. And I wanted Jess to be the adult POV in that formula as well. So the little boy that she winds up taking care of, his fears are so much more external. They’re so much more garish and monstrous, like there’s a werewolf after him. They’re just very much the monster in the closet, the monster under your bed.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-