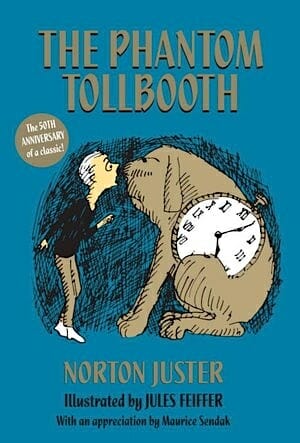

The Phantom Tollbooth 50th Anniversary Edition by Norton Juster

For whom the booth tolls

In literature, entryways into fantastic other worlds come in all shapes and sizes.

In The Chronicles of Narnia, the kids escape dreary old England through the back of a magical wardrobe. In H.G. Well’s classic, The Time Machine, the transporting device actually turns out to be … well, a time machine, a contraption put together, one guesses, with wheezing steampunk springs and gaskets. In Harry Potter books, a port key to a distant location might be some old pair of socks or a lost comb or Ron Weasley’s underwear—anything, really, that might be enchanted to allow fantastic passage from one place to another.

In 1961, a strange book came out telling of a normal, bored kid named Milo who gets home from school one day to find a box in his room. In a few paragraphs, Milo assembles from that box, like the world’s biggest origami, a cardboard tollbooth, complete with a fine little electric car—a preVolting development.

Milo drops a coin into the toll booth and drives through. He’s immediately in a place that many reviewers for many years have compared to Alice’s Wonderland—a world where logic is logical but nonsensical, and where what you actually know in your head and heart matters more than spells and wands.

The architect of all this fun and foolishness actually worked as … an architect. Norton Juster came home to Brooklyn from the U.S. Navy and immersed himself in the grown-up workaday world, designing buildings and dwellings. Bored to the bones by it all, he wrote a children’s book.

It happens, as good stories do, that in his Brooklyn apartment house, an upstairs neighbor named Jules Feiffer had just gotten papers from the Navy. Feiffer got a look at Juster’s story in progress and spontaneously produced a few illustrations for the book, and they nicely fit the fanciful text. The book found a publisher. When The Phantom Tollbooth came out, it drew children like a magnet—surely one of the most curious books to ever captivate the juvenile mind.

The Phantom Tollbooth, like John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and like L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, gives us the story of a naïf, this boy Milo, and his quest of discovery and self-reliance. The world beyond the toll booth has no wizards and dragons, at least in the traditional sense. Milo’s car takes him into a completely metaphorical land called The Kingdom of Wisdom, a place in turmoil because two beautiful princesses of the kingdom, called Rhyme and Reason, have been taken away, leaving discombobulation and bumfuzzlement.

In the Kingdom, rival potentates—King Azaz the Unabridged and The Mathemagician—preside over Dictionopolis and Digitopolis, respectively. In Dictionopolis, letters spell power and are believed to be the most important things on earth. In Digitopolis, numbers, of course, add up to influence. Without the sisters, Rhyme and Reason, the two kingdoms have no harmony, the center cannot hold, the falcon cannot hear the falconer, etc. Milo, as good quests will have it, finds himself tasked with bringing these princesses back from the Land of Ignorance to restore peace, love, understanding, and other nicklowian virtues to the world.

Milo’s companions, introduced in clever chapters, turn out to be Tock, a watchdog—literally, a sober, voice-of-reason canine with a clock for a belly—and a Humbug, a wheedling, blustering, all-too-human gasbag … or gasbug. These three heroes set off to rescue princesses, and readers settle back for a good old-fashioned morality play … not about religion, but the great good that learning can bring.

The hero’s quest leads to adventures Thick and Fast. Milo and his retinue meet memorably imaginative characters, such as a maestro named Chroma the Great who conducts all the colors of the world instead of musical notes. They meet a boy named Alex Bing, or most of a boy, anyway—he’s .58 of a boy, to be precise, because the average household has 2.58 kids and Alex’s family already had two kids when he came along, so he’s a .58 child. The travelers encounter a perfectly ordinary-looking chap who introduces himself as the thinnest fat man in the world AND the fattest thin man in the world. Things, as Alice says in her own book, get curiouser and curiouser.

In time, Milo, Tock and Humbug reach the Land of Ignorance, their party happily made wiser through lessons learned en route. But as you might expect, Ignorance presents some real problems—a faceless man, for instance, who announces himself thus: “I am the Terrible Trivium, demon of petty tasks and worthless jobs, ogre of wasted effort, and monster of habit.” Our trio meets the Senses Taker, who distracts them from their quest with inane and trivial questions. As Odyssey found with the narcotic lethargy of the Lotus Eaters, apathetic distraction can cost lives. Almost, anyway.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-