Tom Bissell: Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter

Celebrated journalist does some videogame soul-searching

In April, legendary film critic Roger Ebert doubled-down on an assertion he first leveled in 2005: “Video games can never be art.” His unflinching blog-post dismissal stung gamers the world over, eliciting countless rejoinders. A friend of mine summarized the ensuing fallout quite nicely: “Never have so many gamers expended so many words insisting they don’t care what a film critic thinks of them.”

Tom Bissell’s newest book Extra Lives goes out of its way to avoid such taxonomical hair-splitting. The author is less concerned with defining games than with weighing their emotional impact and capabilities as a vehicle for storytelling. “Anyone who can tell you what a game is, or must be,” he warns early on, “has seen advocacy outstrip patience.”

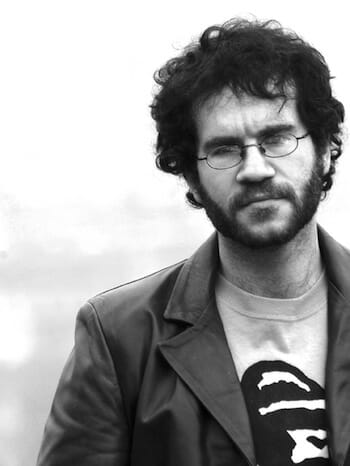

Bissell’s writing portfolio encompasses everything from literary criticism to fiction to history to memoir, but he’s a travel writer at heart. His debut book Chasing The Sea recounts journeys through Uzbekistan, to which he returned several years after his initial visit in 1996 as a Peace Corps volunteer.

There’s a theme of compulsive, Kerouacian movement running through Bissell’s entire oeuvre, and Extra Lives is no different. Only now, the author’s explorations find him not only moving around the globe—Talinn, Las Vegas, Rome—but also through richly imagined digital worlds as far-flung as postapocalyptic Washington, D.C. (Fallout 3), war-ravaged African savanna (Far Cry 2), and human-colonized outposts in the starry cosmos (Mass Effect).

The beauty of travel is that it not only illuminates the world we move through, but the interior world we’re forced to consider as we encounter people, places and customs that chafe our sense of what’s proper. Bissell stresses that this sort of catalytic bewilderment occurs also in videogames.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-