Just A Quick Reminder That SNL Is Paying Its Audience To be There

Screen caps from YouTube

This article was originally published on Humorism, a newsletter about labor, inequality, and extremism in comedy. Subscribe here to get posts like this in your inbox.

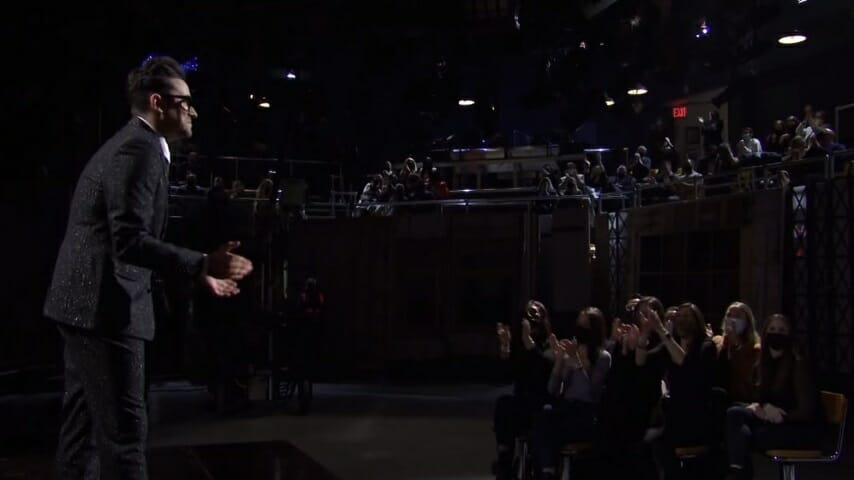

Tonight in New York City, one hundred or so people will file into Rockefeller Center in groups of up to nine. There they will receive staggered Covid-19 rapid tests and slowly make their way into Studio 8H, each group seated in its own section, separated from other sections by at least six feet. When the show begins, they’ll laugh and cheer and applaud through their masks. Given this episode’s host and musical guest, Nick Jonas, they’ll likely even let out a few screams. When the show ends, they’ll slowly file out of the studio. As they leave, each person will receive a check for $150.

Saturday Night Live’s peculiar adaptation to New York’s reopening guidelines has mostly faded into the background since it was first announced. As so often happens when SNL makes headlines, they quickly revert to the same old conversations: who’s hosting, who’s doing which impression, what a funny digital short that was, how pitch-perfect was that musical sketch, blah blah blah. The simple fact of the show’s production, in studio, with a live audience, during a pandemic, has become an unremarkable part of life instead of what it should be: some bonkers dystopian bullshit happening every Saturday night for the whole world to see.

This is very lucky for SNL, because the whole scheme withers under a little sunlight.

As variousoutlets reported in October, SNL is paying audience members in an effort to comply with the state’s guidance for media production. That guidance reads as follows: “Responsible Parties must prohibit live audiences unless they consist only of paid employees, cast, and crew. Employees, cast and crew may make up a live audience of no more than 100 individuals, or 25% the audience capacity, whichever is lower. Live audiences must maintain social distance of at least six feet in all directions.” The logic here is that by paying audiences, SNL converts them into employees, and indeed an audience member I spoke to after the premiere said her (unexpected) paycheck included a vendor number. This suggests SNL is taking an expansive view of the word employee, whose definition isn’t quite spelled out in the state’s guidance: under employment law (as opposed to agency regulation), a vendor is more likely to be considered a contractor than an employee. Still, Chicago-based labor attorney Will Bloom told me that while SNL may be playing fast and loose with the spirit of the rules, if push came to shove, NBC could likely persuade a court that live audiences are integral to its operations and are therefore its employees.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-