Luther Burbank, The Maker of Modern Agriculture

A lot of people, even self-proclaimed foodies, do not know who Luther Burbank was. I find this odd not only because of his legacy, an almost supernaturally prolific career in plant breeding that gave us many of the foods we eat today, but because in his lifetime the man was the horticultural equivalent of a rock star, and counted among his admirers Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, John Muir, and Helen Keller. Burbank was charismatic, brilliant, tireless, and despite an elementary school education, possessed of an almost mystical ability to conjure plant life. Everyone knew who he was.

Burbank was born in Lancaster, Mass., in 1849. He was the 13th of 18 children. After the death of his father he used his inheritance to purchase a few farm acres and went to work on developing a potato that would have a natural resistance to the blight that sparked the catastrophic crop failures in mind-19th century Ireland. The result was the Idaho or Burbank Russet, which is now one of our dominant agricultural crops and the source of practically every French fry you have ever eaten. He moved to northern California, where the growing season was longer, with the money he made selling the rights to the Burbank Russet.

It sold for $150. If that sounds wild to you, don’t worry—it did to him, as well. As it turns out, there are serious difficulties with making money as an inventor when your inventions are living, reproducing plants. More on that in a minute.

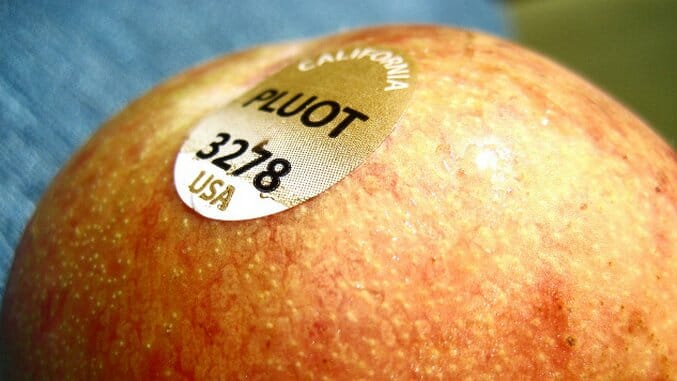

A lot of scientists will tell you that horticulturalist Luther Burbank was not one. In a way, I think that’s probably right—and he might not have minded the exclusion, though it bothered him when people called him a “wizard.” (He felt it smacked of “hocus-pocus,” which he’d have hastened to note was not his thing either.) A devoted acolyte of Darwin, he happened to be a non-scientist who developed over 800 varieties of plants in a 50-year career. Many of them never went to market, some became unfashionable and faded away, some—like the white blackberry and the spineless prickly pear—were flops. But he’s the man you can thank not only for Idaho potatoes, but also for the pluot, most of the plums you’ve ever eaten (including the ubiquitous Japanese hybrid Santa Rosa), rainbow Swiss chard, red sorrel, and a huge number of apples, pears, peaches and nuts.

Luther Burbank at his home, Santa Rosa, California, circa 1910. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

If we look at the evolution of Western natural history, we see a pretty clear division that probably begins somewhere around first century Rome and definitely hits full acceleration in the Renaissance. Two paradigms emerge where the study of natural philosophy is concerned (in fact the term “scientist” wasn’t even coined until the 19th century). On the one hand, there are the descendants of Bacon and Descartes, Empiricism, the sons and daughters of statistics and the double-blind study—in other words, the brand of scientific inquiry that holds sway over most of the sciences in the modern United States.

That wasn’t Burbank by a long mile.

Burbank belonged to the school of the oddball mavericks I will call “Orphics” as opposed to Cartesians or Baconians. Not coincidentally, Orpheus was not a real person, but a powerful figure in Greek mythology—a superbard whose singing and lyre playing could charm gods, move mountains and rivers, and cause trees and flowers to spring from the ground. “Orphic” thinkers are (and were) not scientists in the Baconian sense. They were intuitives, embracers of metaphor. Some of them kept better notes than others; some were better funded than others. Some were burned at the stake by the Spanish Inquisition. But these people made many of the quantum leaps in our understanding of how the natural world works. Giordano Bruno and Carolus Linnaeus, Paracelsus and Swedenborg, Darwin and Rudolph Steiner—and certainly, whatever you want to put on his business card, Luther Burbank.

For whatever reason, Burbank had an affinity for plants, for understanding both what they were and what they could be. He was keenly aware of the subtle contracts trees and grains and flowers made with birds, insects, and other animals, including humans—how they tended to “advertise” for pollenizers by enticing them with sugar or perfume or bright colors in order to keep their genes alive. He was a preternaturally diligent laborer. He was also a notoriously crappy note-taker, which earned him the disdain of much of the scientific community as well as the revoking of a grant from the Carnegie Foundation. Not everyone was seduced by his “wizardry.”

It is worth noting that the prolific career of this one man gave rise not only to the Wickson plum, the Shasta daisy, freestone peaches and blight-proof chestnuts and potatoes, but also to the legislation that has made possible companies like Monsanto and ADM.

He used cross-breeding, grafting, June-budding, hybridizing and selection techniques to create everything from quinces and chestnuts to a scented calla lily to a walnut that grew furniture-grade hardwood twice as fast as its ancestors. He bred artichokes and cardoons, sorghum and quinoa, pineapple guavas and cane berries. He was interested in fruit trees and animal fodder, tropical plants and temperate ones, ornamentals and edibles. He was interested in beauty and abundance for their own sakes and he was interested in plant inventions that stood to improve the quality of life for humans; promoting access and diversity, and solutions to food supply and hunger crises. He was, by all accounts, interested in just about everything. Hundreds of species and cultivars owe their existence to Luther Burbank, and there are uncountable numbers that might have briefly existed and been lost.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-