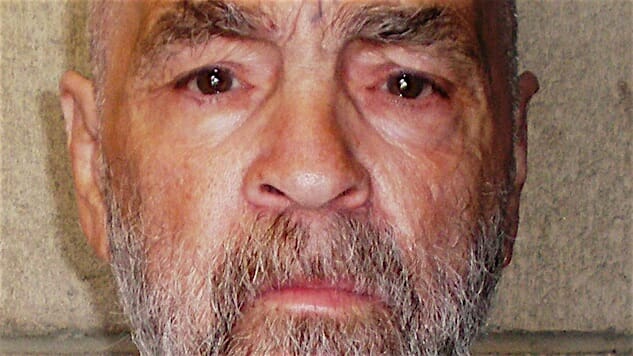

Charles Manson Is Gone, but Movies Won’t Let Him Stay Dead

A 48-year obsession in film

There’s an argument to be made that you can’t really understand the 1960s and the hippie movement without grappling with Charles Manson—the dark reflection of the free love and mind-expanding drug wave that radiated out from Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco.

There’s another, better argument to be made that this gives Manson way too much credit. Reading about his life paints a picture of a man who was hurt by all those close to him and abandoned by a system that, by 1969, had kept him behind bars for longer than he’d ever been outside them. In light of that, why wouldn’t he grow to be a manipulator of people?

Every detail seems to belie the fanciful idea that he was some magical snake charmer. His cult’s twisted ideology supposedly spreads a message of evil to this day, but if you actually read accounts of his sermonizing, you find it was inconsistent nonsense in which he claimed to be Jesus and/or Satan, in which a race war was coming, in which the Beatles were talking directly to him through song. He was supposedly a criminal genius, but went ahead and had people murdered in places easily traceable to him, leaving evidence about willy-nilly so that only the well-documented incompetence of the Los Angeles police kept him from being apprehended sooner. He is renowned as a mass murderer yet didn’t actually kill any of the people with whose deaths he was charged and convicted. He was a criminal mastermind, yet he was caught almost immediately. He was a figure of fascination because he hobnobbed with famous people like the Beach Boys for a bit, but the impression I always get of the ’60s was that you could Almost Famous your way into that scene pretty easily if you had the right drugs and talked the talk. And most risibly, he’s regarded as this living martyr to Satanism and anarchy, but he remains alive only because the State of California commuted his death sentence to life imprisonment—otherwise we’d have been spared his occasional insane outbursts.

All that aside, Manson and the odd and damaged people who carried out his murders made an indelible impression on a terrified public, and the proximity of those murders to Hollywood high society preyed on the minds of the people who turn the cranks and pull the levers of the dream factory.

Those two nights in 1969, during which members of Manson’s “Family” Leslie Van Houten, Steve Grogan, Susan Atkins, Linda Kasabian and Patricia Krenwinkel killed seven people in their homes and decorated the crime scenes with bloody epithets they intended to start a race war known as “Helter Skelter,” remain infamous 48 years later.

Though the following list isn’t by any means comprehensive—that would be impossible—it’s a look at the breadth of the Manson obsession over the last half-century.

Tripping (1999)

It’s not a film that has anything to do with Manson where subject matter is concerned, but to understand the world through which he slithered, this documentary about proto-hippies The Merry Pranksters—the entourage of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest author Ken Kesey—includes archival footage of their mythologized 1964 bus trip. It might not tell you much about the day-to-day life of the 1960s, but it does its best to put you into the acid-induced mindset that was the counter-culture at the time, through the eyes of those who carried the banner for it.

Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969)

It’s possible the only reason Bobby Beausoleil wasn’t a participant in the Tate and LaBianca murders that made the cult infamous is that a few days earlier he had been arrested for the murder of another man. A regular on the Spahn Ranch compound where Manson and his devotees lived and performed orgies, Beausoleil was also an aspiring actor and artist, much like Manson himself. And, also like Manson, his ambitions would never come to fruition. This odd curio, another film which likewise doesn’t feature Manson and was shot before the evil acts that made him infamous, is still so tied in with the circumstances surrounding him that it must be mentioned.

An 11-minute film composed of whatever footage director Kenneth Anger could salvage, features a soundtrack by none other than Mick Jagger and Beausoleil playing Lucifer. The raw film was intended to be entitled Lucifer Rising, but a dispute between Beausoleil and Anger ended in Beausoleil absconding with the footage and allegedly burying it somewhere in Death Valley out of spite. It’s a weird, dark artifact that, like everything about the Manson phenomenon, drags famous artists into the realm of incoherent mystical weirdness.

The Other Side of Madness (1971)

Combining documentary footage with carefully staged reenactments—some of them in the same homes where the murders took place, for God’s sake—this black-and-white bit of sensationalism is most notable for having been made while the horror of the incident was still fresh. While the circumstances of it suggest crassness, the film itself is actually straightforward and dry about the proceedings themselves. It’s too bad the actors are kind of terrible.

Manson (1973)

For perhaps the most unnerving look at the cult of the Manson Family itself, this documentary features on-camera interviews with several family members before and during the trial for the Tate and LaBianca murders, and with prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi.

Every documentary or dramatic retelling of the murders, every portrayal of the cult in fiction, pales in comparison to actually watching Family member and (future would-be assassin of President Gerald Ford) Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme calmly and evenly say, on camera with rifles and knives, that the Family will just go ahead and kill anybody who threatens them.

House of 1,000 Corpses (2003)

And for a callback to that very same on-camera interview, and for literally no other reason, you can sample Rob Zombie’s strange gore-fest. It’s a mess of a movie, but one of the things that jumped out at me—and actually made me angry—was the inclusion of a random little vignette, one of many peppered throughout the movie as bizarre non-sequiturs, in which one of the secondary characters spouts off a ridiculously specific line of dialogue lifted straight from the aforementioned documentary. The only reason I recognized it was that I had taken a class entirely about the Manson murders and ’60s counter-culture and had mere weeks before seen that documentary.

It’s an example of the most deeply vexing pet peeve I have about Manson and everything surrounding him, which is the emblematizing of his cult’s brand of incoherent nonsense and its use as some sort of banner to rally the anarchists in life. It makes no deeper statement, no more interesting connection, no compelling parallel. It is in a movie about dumb teens getting killed by weird hicks. It is a microcosm of every ham-handed Manson reference ever.

Helter Skelter (1976)

This two-part TV movie is an extended dramatization of Bugliosi’s tell-all accounting of his investigation and prosecution of Manson and the members of the Family. It does add some dramatic flourishes, including Bugliosi telling off Steve Railsback’s Charles Manson in one hilariously incorrect-in-retrospect exchange in which Bugliosi tells Manson he’s already been forgotten.

For the real rundown on the investigation and the prosecution, Bugliosi’s book of the same name, on which this movie is based, is your best source, detailing every stage of the murders’ aftermath. This film’s first part plays out like a procedural of the investigation, its second a procedural about the trial. For a closer look at the twists and turns that landed Manson in prison for the rest of his life, this is an important watch.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-