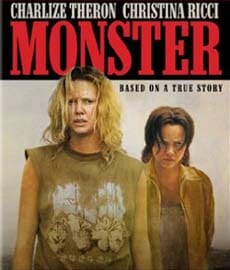

Monster

Serial killers in the movies surely outnumber serial killers in real life. But our films gaze at these characters with a unique fascination, like they hold the secret truths of the universe, like they embody our shortcomings as a people, full of sadness and rage, cast out of our midst for failing to meet the rigid requirements of our society.

American movies seem just as fascinated by the working class insularity of America’s middle and Southern states, and it’s not unusual for a film to meld the two fascinations, audience transfixed before attractive young actors who don the accents, the clothing, and the killin’/lovin’/runnin’ ways of the Southern outlaw—whether it’s Brad Pitt in Kalifornia, Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis in Natural Born Killers or Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek in Badlands. Despite the high-minded implication of movies about serial killers—that we need to understand the deviant among us to better understand ourselves—these stories are usually more like freak shows than social commentary. Fritz Lang’s classic M set the bar in 1931 by examining the workings of a society and the ironies of a culture that wants to rid itself of a cancer it may have created, but M is the rare exception.

To its credit, Monster, the feature-film debut of writer/director Patty Jenkins, aspires to that ideal. It’s based on the true story of Aileen Wuornos, but it’s no freak show. It truly wants us to empathize with its main character and not rush to judgment against her, and it undermines a basic assumption of the genre—that killing is a male tendency left unchecked—since the killer here is a woman, played by an unrecognizable Charlize Theron. Aileen’s violent tendencies seem more like the survival instinct of a cornered animal than an innate thirst for blood.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-