The 20 Best True Crime Documentaries on Netflix

More than 50 years after the publishing of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, a pioneering work of the true crime genre, we’re experiencing a boom in the popularity of true crime, especially in film and television. From Making a Murderer to O.J.: Made in America to The Jinx, the last few years could be considered a Golden Age for telling real-life stories of misery. There’s even been a rise in parodies of the genre, like American Vandal or Steve Martin’s Only Murders in the Building. Netflix in particular has made a name for itself in this niche, acquiring a strong slate of indie docs and producing some of their own, higher-profile works. True crime documentaries on Netflix are a subgenre unto themselves. Still, this is always a tricky genre to navigate: for every noble award-winner like The Thin Blue Line, a lurid alternative is likely to pop up in your recommendations. (Please, Netflix, don’t make us watch Josef Fritzl: Story of a Monster.)

Below, we help separate the truly compelling offerings from their trashier counterparts with our list—including movies, TV shows, and miniseries—of the best true crime documentaries available on Netflix.

1. Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez

1. Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez

Director Geno McDermott’s three-part 2020 Netflix documentary is as much a story of fame and power as it is what happens when mental illness, abuse, and repeated head injuries like the ones inflicted upon football players go unchecked. Flashing between depictions of New England Patriots’ Aaron Hernandez as a rising football star with an abusive, alcoholic dad to the one we know from recent headlines—his murderous rage and his killing of his friend, Odin Lloyd, and others—audiences see how many lost lives could have been avoided if authorities had only paid attention. This includes Hernandez’s own. He hung himself in his jail cell. An autopsy report found a “severe” case of CTE.—Whitney Friedlander

2. The Two Killings of Sam Cooke

2. The Two Killings of Sam Cooke

The Two Killings of Sam Cooke is another installment of Netflix’s original music documentary series ReMastered, attempting to create a holistic portrait of American soul legend Sam Cooke—one that doesn’t carelessly whitewash his story just because his crooner soul also appealed to white audiences. In an effort to save his “murdered legacy,” the film examines his early roots in black churches, the evolution of his music, his impressive business acumen, and his political activism later in life, which is believed to have led to his eventual murder. As Cooke became an increasingly influential cultural figure, his associations with other politically active black figures like Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, and Jim Brown posed a threat to the racial status quo. Cooke’s murder arises as an integral point of discussion in the film, and the details to this day are still muddy. Just as Cooke began writing politically-minded music—the sequence where “A Change is Gonna Come” plays in the background is breathtaking—his life was tragically cut short, and the film is a reminder of his unbelievable talent, and his embrace of blackness, that history largely forgot. —Lizzie Manno

3. Wild Wild Country

3. Wild Wild Country

Some documentaries are more dedicated than others to telling a story from multiple and opposing viewpoints. Wild Wild Country’s primary interviewees—some members of the cult, some residents and law enforcement agents in the Oregon county where the Rajneeshpuram commune was located—seem to have inhabited two separate realities: If you made a Venn diagram, there would be virtually no overlap. In fact, nearly four decades later, the devotees of guru Bhagawan Sri Rajneesh still appear to inhabit a separate reality. Even the ones who fled the cult. Even the ones who were indicted for everything from biological warfare and voter fraud to attempted murder.

In the early 1980s, a guru with an ashram in Poona, India relocated to an 80,000-acre ranch outside the minuscule town of Antelope, Oregon, and then proceeded to be in the news constantly for one crazy thing or another. By the mid-’80s they had disbanded, after a series of legal scandals that ranged from the weird to the outright horrible. Wild Wild Country tells their story in lavish detail, and since they were such a media curiosity at the time there is an incredible wealth of archival footage with which to work. It’s a rambling, if generally thorough, document of a strange historical event, largely recounted by the people who were there, which rarely takes sides and certainly leaves open to interpretation which truth holds more water. Wild Wild Country’s takeaway questions are certainly timely enough: How do we, as a nation, handle immigration and integration? More importantly, why do we make the choices we make in that space? What happens to the hard-and-fast constitutional argument for separation of church and state when a religion is allowed to form its own government and arm its own military? Is it religious persecution when you’re investigated for an attempted murder you actually did attempt? Do the complaints of one side invalidate the grievances of the other? What emerges clearly is that lies are often as serious as salmonella, or the bacteria-vectoring beavers the cult allegedly tried to put into the Antelope reservoir. Once there’s literal and figurative poison in the well, it becomes difficult to cast yourself as either persecuted or enlightened. —Amy Glynn

4. Casting JonBenet

4. Casting JonBenet

An unlikely cross-section of humanity also populates Casting JonBenet, which boasts a provocative idea that yields enormous emotional rewards. Filmmaker Kitty Green invited members of the Boulder, Colorado community where JonBenet Ramsey lived to “audition” for a film about her. But in the tradition of Kate Plays Christine or The Machine Which Makes Everything Disappear, that’s actually a feint: Green uses the on-camera interviews with these people to talk about Ramsey’s murder and the still-lingering questions about who committed the crime. She’s not interested in their acting abilities—she’s trying to pinpoint the ways that a 21-year-old incident still resonates. It’s a premise that could seem cruel or exploitative, but Casting JonBenet is actually incredibly compassionate. Green wizardly finds connective tissue between all these actors, who have internalized the little girl’s killing, finding parallels in their own lives to this tragedy. High-profile murders like Ramsey’s often provoke gawking, callous media treatment, turning us all into rubberneckers, but Casting JonBenet vigorously works against that tendency, fascinated by our psychological need to judge other people’s lives, but also deeply mournful, even respectful, of the very human reasons why we do so. —Tim Grierson

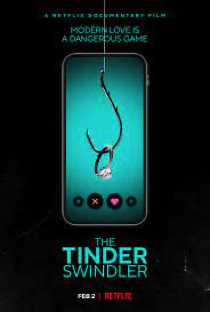

In 2019, Norwegian newspaper VG published an article titled “The Tinder Swindler,” which sent shockwaves through the general public on par with The Atlantic’s “The Truth About Dentistry,” or the New York Times’ “Who is the Bad Art Friend?” The article follows a man named Shimon Hayut who spent years of his life posing as Simon Leviev, the heir to a behemoth Israeli diamond fortune. He adopted this persona to court women on Tinder and, once he has earned their trust, to trick them into loaning him hundreds of thousands of dollars—money he would then use to woo his next victim. As is the case with most popular IP, “The Tinder Swindler” was picked up for adaptation at lightning speed, and developed into a documentary by the masterminds behind Netflix’s Don’t Fuck with Cats, the deep-dive miniseries into the stranger-than-fiction story of the rise-and-fall of a porn-star-turned-cat-torturer-and-maybe-cannibal. Directed by Felicity Morris, The Tinder Swindler is not dissimilar to Don’t Fuck with Cats in that it is delightfully high-concept, bringing with it a similar frenetic energy and playful teasing out of twists. More than anything The Tinder Swindler has its finger on the pulse of what viewers want in a true crime documentary. At just under two hours, it doesn’t drag on longer than it needs to. It is short, snappy and succinct. It also effortlessly fits in everything we look for in a doc like this: A retelling of the crime and the investigation (the latter being, in this case, even more interesting than the former), non-distracting reenactments and an engaging tone, which Swindler accomplishes by whipping around the globe to exotic locations—all paired with a lively soundtrack. —Aurora Amidon

6. The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson

6. The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson

Director David France’s documentary portrait of “the Rosa Parks of the LGBT movement” has come under fire from trans filmmaker Reina Gossett, who accuses France of purloining the idea for the film from a grant application she submitted to secure funding for her own film about the pioneering trans activist. Still, in bringing wider attention to Johnson’s life and work, the film is a worthwhile reminder that trans women of color were and remain queer revolutionaries—and that they were and remain disproportionately likely to be murdered, often in cases that are never solved. Following trans activist Victoria Cruz as she tries to find the truth behind Johnson’s 1992 death—which the police swiftly ruled a suicide despite indications of foul play—France blends true crime and the biopic into an illuminating treatment of a true American heroine. —Matt Brennan

7. This Is a Robbery: The World’s Biggest Art Heist

7. This Is a Robbery: The World’s Biggest Art Heist

Oftentimes true crime series have such heavy, soul-crushing topics. Though fascinating, they can be difficult to watch all in one sitting. A select few true crime series can have both an enticing storyline and not be incredibly sad or traumatizing; thankfully, Netflix’s new This Is a Robbery: The World’s Biggest Art Heist fits the bill. Similar to Sandi Tan’s documentary Shirkers about missing strips of film, or perhaps even the recent McMillions on HBO, This Is a Robbery is a lost and (sort of) found caper that’s actually quite fun to watch. Instead of the McDonald’s Monopoly game prize or a student film, the missing items here are paintings. Huge museum paintings, to be exact.

This Is a Robbery explores the mystery of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, a gorgeous spot that’s well-known to most Boston locals but fairly off-the-map for those new to the city. Right away, the first episode does exactly what it’s meant to do: pique your interest. A museum robbery sounds like something straight out of a James Bond film, and This Is a Robbery treats the topic as such. The music growls as talking heads recreate the night of the crime from memory; the dramatization throws us into the museum to witness the paintings being torn from the walls. Was the security guard in on the job? Maybe the ghost of Isabella Stewart Gardner herself? Or perhaps a Boston mob was involved? The mystery of the museum is enough to hook one’s interest, and the mystery starts strong. —Fletcher Peters

8. FYRE: The Greatest Party That Never Happened

8. FYRE: The Greatest Party That Never Happened

The disastrous and fraudulent Fyre Festival has been a meme ever since it imploded in epic proportions in 2017 on the Bahamian island of Great Exuma. The festival was marketed to well-to-do millennials and influencers as the most premium and luxurious music festival getaway, and folks bought into it in droves. When festival-goers showed up, it was apparent there wasn’t enough food, water, or housing. Big-name artists began to pull out, resulting in its cancellation and the eventual stranding of attendees. The festival’s purported “mastermind” and yuppie narcissist Billy McFarland fraudulently acquired funds for the festival and has since been sentenced to six years in prison. FYRE: The Greatest Party That Never Happened pulls back the curtain on how A-listers like Kendall Jenner, Bella Hadid, Pusha T, Blink-182 and marketing giant FuckJerry were duped into associating themselves with and legitimizing this high-level scheme. In the documentary, Fyre employees and outside agencies hired to work on the festival share how a charismatic McFarland could charm investors and top-of-the-line industry professionals into buying his vision, despite a lack of detail on what the festival would actually look like. This film has everything from humor and ego to glamor and gross human negligence. It’s a case study on how bold ambitions can quickly overshadow logistics and completely mask reality. —Lizzie Manno

9. The Keepers

9. The Keepers

Who would want to kill a nun? Director Ryan White tries to find out in Netflix’s seven-episode 2017 docuseries surrounding the murder of Catherine Cesnik. The Baltimore-based nun, who was also a beloved English and drama teacher at an all-girls high school, went missing in November 1969; her body eventually discovered the following January. A cold case with the Baltimore PD, White and his team interviewed “Sister Cathy’s” former students and friends as well as investigators and detectives to come up with the theory that the 26-year-old learned a priest was sexually abusing students—and that authorities were covering it up. Fans of The Wire will also appreciate the strong Baltimore accents. —Whitney Friedlander

10. Long Shot

10. Long Shot

Among all true crime documentaries, Long Shot holds the impressive and bizarre honor of being the only one in which Curb Your Enthusiasm plays a key role and in which Larry David is a talking head. If that doesn’t hook you into watching the strange case of Juan Catalan’s arrest, not much else will. Director Jacob LaMendola’s film isn’t the most stylish or intricate—in fact, it’s a workmanlike 39 minutes with just enough stage-setting to get to the big twisty payoff. The biggest moment of emotion comes from a production assistant grappling with the impact he, the low man on the totem pole, had at the time. But it’s not a bad thing. The substance is there. It makes for a great cocktail party anecdote. And honestly, between the lengthier, headier films and drag-your-feet series flooding this subgenre’s market, it’s quite a feat to get in and out with a well-told story in such an elegantly clipped runtime. There are no unsolved questions as to Catalan’s innocence. He didn’t kill anyone. But proving that is where the secondhand fun, the Sherlock-esque mystery of it all, comes into play. And if Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s nitpicking self somehow time-traveled his way into the 21st century, this is a criminal investigation with the exact kind of oddball detail that he’d love to bury for his fictional investigator to dig right back up again. —Jacob Oller

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

5.

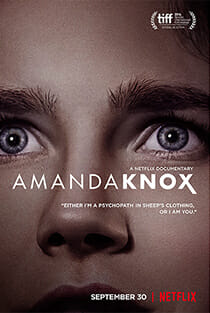

5.  11. Amanda Knox

11. Amanda Knox 12. Surviving R. Kelly

12. Surviving R. Kelly 13. Abducted in Plain Sight

13. Abducted in Plain Sight 14. Team Foxcatcher

14. Team Foxcatcher 15. The Staircase

15. The Staircase 16. Evil Genius

16. Evil Genius 17. Don’t F**k With Cats

17. Don’t F**k With Cats 18. Making a Murderer

18. Making a Murderer 19. Wormwood

19. Wormwood 20. Strong Island

20. Strong Island