Longlegs Immerses You in Evil and an Unforgettable Nicolas Cage

The first thing I wanted to do after seeing Longlegs is take a shower. Some horror movies have you looking over your shoulder on the way out of the theater, jumping at shadows in the parking lot. These are the horror movies that follow you. Longlegs doesn’t follow you. You’re drenched in Longlegs. It’s all over you—in your hair, on your clothes—by the time the credits roll. Its fear is less tangible than a slasher or a monster, even less than a demon. It’s just something in the air, in the back of your mind, like the buzz of a fluorescent lamp. Oz Perkins’ Satanic serial killer hunt is his most accessible movie yet, putting the filmmaker’s lingering, atmospheric power towards a logline The Silence of the Lambs made conventional. Precisely crafted and just odd enough to disarm you, allowing its evil to fully seep in, Longlegs is a riveting tale of influence and immersion.

We’re the first to fall under its spell, as Perkins drowns us in unyielding walls of color (bright red titles, snow-white landscapes) and confines us to the past’s boxy aspect ratio. A playfully scary vignette plays out, a stiff apéritif for us to roll around on our tongue as the screen expands into the rectangular present of the film’s ‘90s. There, FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) is next to succumb.

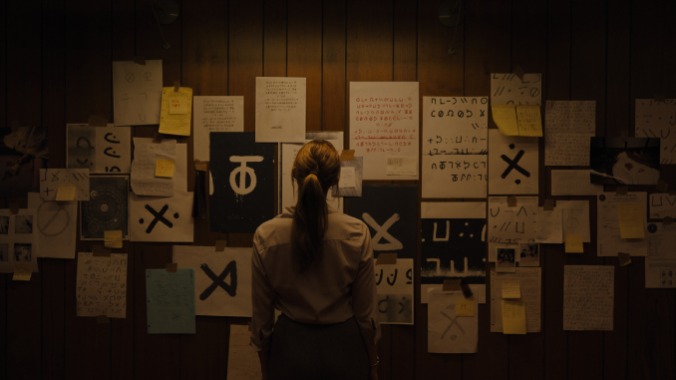

After Lee successfully, and mysteriously, locates a killer on little more than a hunch, her charming boss, Agent Carter (Blair Underwood), assigns the quiet savant to a long-dormant investigation into a suspect known only by how he signs the coded letters found at the crime scenes: Longlegs (Nicolas Cage). Someone has been killing nice families with nice daughters in nice white houses—or somehow making them kill each other—for decades. Cutting through the numerology, inverted crosses and other occult ephemera that have been deteriorating since the Manson ‘60s might save the next targets.

Only, the mystery to be solved isn’t Clue. You’re not filling in weapon, location, suspect. The question crawling under Longlegs’ skin is how grounded this case actually is, whether it’s a truly by-the-book procedural or whether that book is bound in skin and filled with spells.

Though this feels like familiar territory for Monroe, who’s made a name for herself in genre films ranging from It Follows to Watcher, the relationship between hunted and hunter blurs beyond that of Final Girl and Slasher, and her performance adapts in kind. Lee is tight-lipped and uneasy in her own skin, a child’s soft voice wrapped in a blue FBI windbreaker. But she doesn’t balk at corpses, or head for the hills once she realizes she’s on Longlegs’ radar. Something’s tugging her forward, just like something tugged her towards that killer she found, blindly, like pulling an ace from a deck of cards. Monroe conveys all this by keeping her physicality subdued and her personality repressed, which locks in perfectly with the world around her—particularly her criminal foil.

Longlegs could also feel like familiar territory for Cage, at first glance. And that’s all we get at first, glances. Like any good monster movie, we’re denied a close look at Longlegs for a decent chunk of the movie’s three segments, but once we see him, that’s all you can think about. Longlegs, with his stringy hair and all-white wardrobe, looks like Dickens’ ghost of glam. Channeling the other side of Mandy’s psychedelic hellscape, Cage moves like an aged rocker, once lithe and fluid, his strange gestures flitting between choreography and ritual. Swollen and makeup-caked like a KISS member’s corpse, Cage mugs and clowns with his Bogdanoff face, tearing at your psyche before finally relenting with some more traditionally vicious evil. Perkins allows Cage to max the volume out, clawing at the limits of the human voice until it tears free into the screeches of Zilgi’s score. Cage may have famously been cast as Superman, but he’s given the Joker performance of a lifetime. It’s big, and it’s a nightmare.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-