The Best Movies of 1980

Having just climbed out of the 1970s and with the Star Wars machine still powering up, the year 1980 is still mostly calm compared to the rest of the decade that would follow. But for whatever it might have lacked in spectacle, 1980 makes up for in classic, genre-defining classics whose directors would mostly go on (or continue) to make meaningful movies that would help define the decade as a whole. For this list, we’ve tried to include some films beyond the usual suspects. (What fun would it be, otherwise?)

Here are the best movies of 1980:

15. Personal Problems (Bill Gunn)

Bill Gunn’s Personal Problems, a “meta soap opera” that intimately follows the interpersonal relationships of a Black New York family, can be considered a 1980 film in the sense that it was completed that year, yet it only received a few one-off screenings in its own time, remaining largely unseen in full until Kino Lorber’s essential 2018 restoration. The brainchild of writer Ishmael Reed, Personal Problems plays in two episodes, a structural remnant of its origins as a PBS-declined television pilot. Before that, it aired as a six-part radio show. These pre-existing roots of collaboration laid the groundwork for a film that would thrive on improvisation, both in front of and behind the camera.

We first meet Harlem ER nurse Johnnie Mae Brown (Vertamae Grosvenor), originally from the Gullah island Daufuskie off the South Carolina coast, seated against a plain white wall fielding questions from Gunn off-camera. She talks about work, moving North as a child and her poetry. The film is alive with such concerns—quotidian struggles both universal and specific to African Americans, Black migration, art, naturethough these thankfully need not be explained. They exist deeply in the characters, who, lensed on video using 3/4” U-Matic tape, are given space to express and emote in ways at once melodramatic and authentic. Part one mostly covers Johnnie Mae’s affair with a musician, while part two tracks the aftermath of her father-in-law’s death. Her husband and the men of the family head to a bar to tie one on in honor of the departed, and as they stumble around the industrial riverside of early morning, Gunn, as he does throughout, cuts to the elemental (the motion of water, birds flying), suggesting one in tune with the other. The world abounds with simultaneous serenity and sorrow: the drunken camaraderie of male mourning, the movements of people away from and back to cultural roots, the tearful notes from an adulterous paramour’s piano. Personal Problems is a bracingly original film propelled by life’s inertia, its frustrations and respites imprinted on the images via early video ghosting. —Daniel Christian

14. Breaker Morant (Bruce Beresford)

What pushes men to go against their better character and commit atrocities? Bruce Beresford, one of Australia’s most accomplished veteran directors, sets this question at the center of his historical courtroom drama, which reenacts the arrest, court-martial and execution of three Australian soldiers—Harry “Breaker” Morant (Edward Woodward), Peter Handcock (Bryan Brown) and George Witton (Lewis Fitz-Gerald)—during the dwindling bloodshed of the Second Boer War. The trio stands accused of murdering prisoners of war and thus breaking the “rules” of combat, and though Beresford never suggests their innocence, he does question profusely the farcical hypocrisy of their trial and punishment. This is a big, brawny film shot with an eye for Beresford’s South Australian locations, convincingly staged as South Africa, and attention to crisp composition. —Andy Crump

13. Coal Miner’s Daughter (Michael Apted)

Sissy Spacek ages from 14 to 45 in her career-defining role as Loretta Webb Lynn, the dirt-poor kid from Butcher Holler, Kentucky, who would become the First Lady of Country Music. This unapologetic film is almost a drama, almost a biography and almost a musical. Highlights are vocals by Spacek as Lynn and Beverly d’Angelo as Patsy Cline. Rock legend Levon Helm and folk music icon Phyllis Boyens (in her first and only credited film role) simply become Loretta’s parents Tom and Clary Webb. Coal Miner’s Daughter is all about perfection of performance, and set an incredibly high bar for musical biopics to come. —Joan Radell

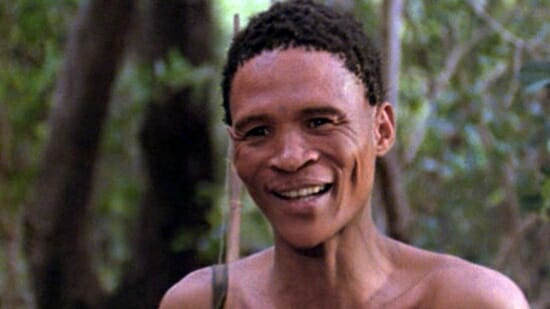

12. The Gods Must Be Crazy (Jamie Uys)

Skipping through genres with as much ease as a lack of purpose, The Gods Must Be Crazy has energy and creativity to spare, but isn’t up to the task of interrogating the continent it dreams of encapsulating. Which is fine! Because Jamie Uys’s hybridized documentary/fish-out-of-water romp/rom-com/cheap-o military action film covers a lot of ground and has a lot of affection for its characters, however ignorantly they represent a traumatic legacy of colonialism in Africa. Uys, a white South African filmmaker, brings us to Botswana, where a member of the San, Xixo (N-Xau), embarks on a journey to the unknown borders of his small patch of the Kalahari to take a Coke bottle (dropped from a passing airplane) far away from his people and rid them of its strange, seductive danger. As Xixo ventures past the frontier of what he knows, so does the movie: We meet Andrew Steyn (Marius Weyers), a biologist who has debilitating anxiety around women, so prefers to isolate himself in the desert; M’pudi (Michael Thys), Steyn’s assistant and grizzled mechanic; Kate Thompson (Sandra Prinsloo), a former office drone and new school teacher in the local village; and a small guerilla army led by Sam Boga (Louw Verwey), who will eventually kidnap Kate and her schoolchildren (?!?), bringing all these disparate threads and genres together at the “end of the world,” off the precipice of which Xixo plans to toss the cursed Coke bottle. Though there’s more than enough social and historical subtext to unearth beneath The Gods Must Be Crazy’s zippy farce, Uys seems content in drumming up a lot of extremely delightful physical comedy and mostly making treacly gestures toward Xixo’s people and just how much he respects their purity, or whatever—never condescending to or chastising them, which is about the best case scenario we can hope for here. Right? —Dom Sinacola

11. The Young Master (Jackie Chan)

Jackie Chan’s second go as director, but first time under the Golden Harvest banner that would vaunt his career, The Young Master is a primordial stew of Hong Kong action-comedy hijinks—unrefined but incredible, an unadulterated early glimpse of an icon beginning to hurl his body through the crucible of his country’s movie industry. Barely supported by a plot, more a series of challenges our innocent martial arts student/orphan, Dragon (Chan), must face to save the soul of his errant brother Tiger (Wei Pai), Chan’s movie offers shenanigans galore, from the opening Lion Dance competition to the concluding some-20-minute battle, during which—pummeled to a pulp by final boss Kam (Hwang In-Shik)—Dragon drinks water from an opium pipe gifted him by a weird old man, giving him super-charged mania that contorts his face into a freakish gurn, his kung fu shrieks the stuff of nightmares. It’s odd and off-putting and exhilarating, and it began a decade of true martial arts movie-making mastery for the young star. —Dom Sinacola

10. Atlantic City (Louis Malle)

Nestled snugly within its titular setting, Louis Malle’s movie is a quieter affair than modern audiences might expect from a film involving gangsters, drugs and gambling. Maybe that’s because the characters featured—especially Burt Lancaster’s aging Lou and Susan Sarandon’s Sally—are not the characters who inhabit center stage in films like Scorsese’s Casino and Good Fellas. Instead, the hopes and dreams and schemes of Lou, Sally, Dave (Robert Joy) and Grace (Kate Reid) are smaller, somehow. With pasts either mostly unwritten, or purposefully smudged and obscured by their own mediocrity, the characters in Atlantic City seem to be on personal arcs that just don’t make as much noise in their ascent (or descent). Yet, as a result, they feel all the more real and, at least with Lou and Sally, worth cheering on. As Lou, supposedly once a gangster and now a small-time numbers runner, Lancaster brings such quiet dignity and seemingly effortless presence to the role that the potential romance between Lou and Sally seems reasonable enough to perhaps even cheer for? By the end of the movie, things have settled into a new normal for the characters that’s both realistic and, somehow, not disappointing. Atlantic Citymay not offer the caloric energy, melodrama or pathos of the other great films of its year, but that doesn’t mean it was any less nutritious. —Michael Burgin

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-