7 Bluegrass Songs that Are Punk AF

Today, bluegrass has a reputation as one of the most conservative genres of American roots music. A lily-white scene with few people of color, the surface of bluegrass today sometimes shows little depth, but underneath bubbles a raw nerve of working-class strife and naked aggression. Watch a bluegrass banjo player burn through a solo, punching out each note like a pugilist, and you’ll be reminded of oi-influenced punk bands like Dropkick Murphys. Listen to a whole, sad story told in fewer than three minutes of songwriting, and you’ll think of The Ramones. Check out the “fuck the police” vibes of early bluegrass songs about bootleggers, and you’ll be reminded of The Clash. This is music made on instruments created before amplification, so don’t let the acoustic tones of the music fool you, bluegrass can be as punk as they come.

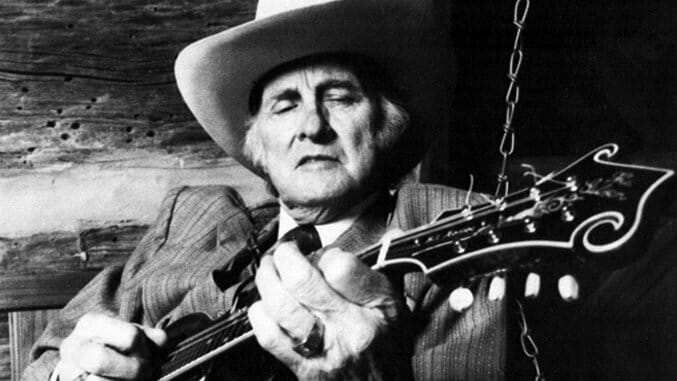

Bluegrass came about in the 1940s from an innovative fusion of Appalachian mountain music, early blues recordings, jazz soloing, church harmonies and a raucous DGAF attitude. It was created by Southern musician Bill Monroe from little Rosine, Ky., and had its heyday in the bands formed by Monroe in the late 1940s and then by his competitors—Flatt and Scruggs, Reno and Smiley, Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys. Every bluegrass band today knows the roots of the music in Monroe’s vision, and they all more or less pay homage to the master even 70 years later. And as it turns out, that master’s vision was remarkably punk, so we’ve rounded up seven bluegrass songs that are punk AF.

1. Bill Monroe, “Mule Skinner Blues”

Recorded in 1940, this is often considered the first real bluegrass single. Recorded by Bill Monroe, “Mule Skinner Blues” features everything we’ve come to understand as bluegrass: intense playing, super high vocals (almost a howl at times) known as the “high tenor,” a fast-rolling beat, and strong influences from African-American musical traditions. All of these are more or less present in punk as well, and Monroe’s innovations, the same innovations that created bluegrass, shook up the country music industry of the time as badly as the first punk albums shook up rock ‘n roll.

2. Flatt & Scruggs, “Foggy Mountain Breakdown”

Besides Monroe, the other key element in the creation of bluegrass is the banjo playing of Earl Scruggs. Discovered by Monroe, Scruggs played the banjo in a totally different way from nearly every other banjo player in America. He took the three-finger picking of his native North Carolina and ramped it up for a new generation, bringing a kind of military precision to his playing. He played faster and harder than anyone else, he played in minor keys, he bent and retuned his strings at will, he utterly redefined the instrument. In the early recordings he made in the late 1940s after leaving Monroe’s band (sparking years of bitter feuding with the master) and starting his own band, the Foggy Mountain Boys, with guitarist Lester Flatt, you can hear him pounding the notes into the shellac so hard that he almost distorts the banjo. It was a sound that was so new and fresh that banjo players across the US literally dropped everything to try and figure out what he was doing. Scruggs is the ultimate badass on the banjo, even today, and “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” has all of this badassery encoded in its musical DNA.

3. Bill Monroe & the Bluegrass Boys, “Bluegrass Breakdown”

Perhaps the quickest comparison between bluegrass and punk comes from two core values of both—speed and aggression. Bluegrass may have come from Bill Monroe, but it came more from his attitude than anything. He was sick to death of the cheap hillbilly bands of his day, sick of Southerners dressing up as goofy hicks and singing songs in-between comedy skits. When Monroe and his band performed, they insisted on dressing up in suits to counter the stereotypes. They played it straight and hard, burning their music into the microphones with an intensity that became their signature. On this track in particular, you can hear that attitude loud and clear. From the jangly discordance of Monroe’s opening chords on the mandolin, to the helter-skelter speed of Scruggs’ racing banjo. At times they seem almost out of sync, pushing themselves so hard that they leave the beat behind. It’s a remarkably punk kind of abandon for bluegrass.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-