The 15 Best Folk & Bluegrass Albums of 2019

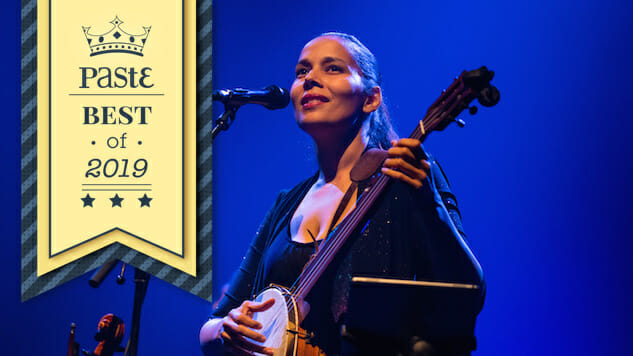

Photo by Lorne Thomson/Getty

When it comes to genre-specific rankings in roots music, things can get a little fuzzy. The definitions for related subgenres like bluegrass, roots, Americana and indie-folk can sometimes appear startlingly different—or they can just all run together. So know that while this list was compiled with the utmost intentionality, it could also be parsed infinite different ways. Folk, in particular, has been all over the map this year. Some artists, like Angelo De Augustine and Laura Stevenson, use traditional folk songwriting techniques, but their music fits squarely in the Bon Iver camp of indie folk. More conventional artists like Rhiannon Giddens (and her supergroup Our Native Daughters) remained steadfast in their devotion to traditional instruments like the banjo, but the work they’re doing in the roots community—the content of their music, the way they use their instruments—is still nothing short of innovative. More singer/songwriter-minded artists like Joan Shelley and Bedouine took after Joni Mitchell this year, while Molly Tuttle and Daughter of Swords ushered us into a new age of folk-pop. Here are our 15 favorite folk and bluegrass albums of the year, ranked.

Listen to our Best Folk & Bluegrass Albums of 2019 playlist on Spotify right here.

15. Patty Griffin: Patty Griffin

15. Patty Griffin: Patty Griffin

This is Griffin’s equivalent of Joni Mitchell’s 1971 Blue album, a ruthless examination of a woman’s choices and relationships over a sound pared down to a minimum. Griffin does two songs alone, two more with only guitarist David Pulkingham and just a handful of players on the other nine tracks. These spare arrangements work only because Griffin’s short, terse lines—both verbal and musical—are strong enough to require no crutches. Back and forth the album goes, from descriptions of crisis to prescriptions for healing and back again. Shadowing everything is an older person’s sense that time is running out. Nonetheless, Griffin says there are still “Luminous Places,” where love “falls out of the sky in millions of pieces” as gently as the arpeggios from Steven Barber’s piano. —Geoffrey Himes

14. Anna Tivel: The Question

14. Anna Tivel: The Question

Portland, Ore. artist Anna Tivel immediately sets the scene on her new album The Question with the words, “In my dream you were beautiful, backlit, noble / in the lowlight of the window you were leaning on the edge.” My first reaction is to call this folk music, but, like so many of the wonderful sounds emerging from roots and Americana circles these days, it transcends that identification. Tivel’s detail-oriented compositions reveal mini universes complete with their own complicated characters and storylines, each of which is embroidered with some distinct sonic embellishment—in the case of “Anthony” and “The Question,” the exquisite strings arranged by multi-instrumentalist Shane Leonard. On the album version of kicker “Two Strangers” those strings are restrained, almost more special for their spareness. In the Paste Studio, however, Tivel opted to perform those three songs alone with her guitar, and it’s not surprising they hold up in a solo acoustic setting. The Question is an album of daring, bold, complicated arrangements, but Tivel’s lyrics are strong enough that they require no extra fuss. She writes a lot of songs while on the road, which would explain the diversity in content, and the aforementioned “Two Strangers” takes shape in the “city lights” of New York. —Ellen Johnson

13. Jimmy “Duck” Holmes: Cypress Grove

13. Jimmy “Duck” Holmes: Cypress Grove

The 72-year-old Holmes is a living link to one of the most vital musical traditions in Mississippi, the high, lonesome blues of Bentonia in Yazoo County. Holmes inherited the Bentonia juke joint, the Blue Front Café, from his parents, and the eerie, minor-key minimalism of the Bentonia blues from Skip James and Henry Stuckey. Holmes became a masterful singer, guitarist and songwriter himself, but he has never had an advocate as influential as the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach, who acted as producer and second guitarist on this recording. Never has Holmes’ music sounded so crisp and clear; seldom has a musician reached as far beyond the usual swagger of the blues to the doubts and dread at its core. —Geoffrey Himes

12. Lula Wiles: What Will We Do

12. Lula Wiles: What Will We Do

Lula Wiles are provocateurs of the best kind, rabble-rousers with the purest intentions. One of the brightest recent signees to Smithsonian Folkways, the Smithsonian Institution’s nonprofit record label, Lula Wiles are a Boston-based folk trio made up of Isa Burke, Eleanor Buckland and Mali Obomsawin, and it seems like they’re hellbent on stirring up country conventions for the better. They make traditional roots music stacked with warm harmonies, acoustic expertise and the occasional electric element, but there’s nothing antiquated about the subject matter of their songs. The three women, who were swapping songs at summer camp in Maine long before they attended college in Boston and became a band, sing with distinctly American voices, but they’re not afraid to question every single thing it means to be just that. To that end, one of their most in-depth tunes is “Good Old American Values,” a single from their label debut What Will We Do, is a striking critique of country music’s and American pop culture’s repeated abuse and misrepresentation of indigenous culture. Elsewhere on the record, Lula Wiles tackle small-town tribulations on “Morphine” and “Hometown,” love’s selfish side on “Shaking As It Turns” and crushes gone wrong on the witty “Nashville Man.” Even as they play raw, old-time melodies and whittled-down folk arrangements, they’re sharing honest, modern music told from a refreshingly smart millennial perspective. —Ellen Johnson

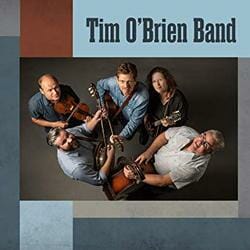

11. Tim O’Brien: Tim O’Brien Band

11. Tim O’Brien: Tim O’Brien Band

With more than 30 albums under his belt, collected under a panoply of different bands and projects, it’s not as if there’s anything more to prove in the bluegrass world, as far as Tim O’Brien is concerned. He’s worked with every legend, and mentored practically every legend in the making for the last two decades. He’s performed at every venue that would ever put a bluegrass band on stage. And he’s written a ridiculous number of songs along the way. And yet, Tim O’Brien persists. At 64-years-old, he keeps right on plucking those banjo strings, and he keeps churning out the new tunes. In recent years and recent albums (2015’s Pompadour, 2017’s Where The River Meets the Road), those tunes have increasingly felt a bit rote, and perhaps O’Brien has been aware of this feeling of entropy. For whatever reason, he returns to us now in 2019 with the first offering from a project both technically new and comfortingly familiar: The simply titled Tim O’Brien Band. Flanked by collaborators Mike Bub, Shad Cobb, Jan Fabricus, Patrick Sauber and Bryan Sutton, they’ve crafted a shared collection of songs that benefit less from sonic exploration and more from air-tight execution. We have to ultimately tip our caps to the guy—the world keeps turning, and O’Brien finds a way to turn with it. Perhaps that’s what he’s trying to evoke by inserting a reprise of the 2008 song “Crooked Road,” which makes reference to the day when O’Brien will finally “say goodbye.” Given his output here, we hope that day is still comfortably far off. —Jim Vorel

10. Daughter of Swords: Dawnbreaker

10. Daughter of Swords: Dawnbreaker

2019 was a big one for Alexandra Sauser-Monnig. The musician best known as one-third of Mountain Man, the folk trio who made their comeback with last year’s beautiful Magic Ship, announced earlier this year that her debut solo record was en route. Dawnbreaker arrived less than a year after Magic Ship, Mountain Man’s second album as a trio and their first after an eight-year hiatus. Dawnbreaker is a gentle 10-song collection of rustling folk-pop. Following previously released singles “Gem” and the title track, spritely tune “Shining Woman” arrived with a fitting video, which premiered here at Paste. Documenting a chance encounter with a striking woman, the song works like folklore, as if the woman in question (portrayed in the video by one of Sauser-Monnig’s friends who donned a pair of “shining” gold pants) is so arresting she’s not even real. Was she ever really there? “She rode away into the breeze,” Sauser-Monnig sings over a quietly looping drum beat and a polite electric guitar. The video culminates in a twilight gathering of cyclists that looks like a lovely way to send off the day. —Ellen Johnson

9. Molly Tuttle: When You’re Ready

9. Molly Tuttle: When You’re Ready

Acclaimed bluegrass guitarist and singer/songwriter Molly Tuttle released her debut full-length album, When You’re Ready, this year on Compass Records. It’s exceedingly bright, honest and energetic and features artists like Jason Isbell, Rachel Baiman and Sierra Hull (Tuttle’s childhood friend who she’s been collaborating with for years). Tuttle may have gotten her start in bluegrass and roots circles, avenues where she’s still wholeheartedly embraced, but When You’re Ready is a sonic leap forward—Tuttle tries on both pop and rock sounds throughout. Tuttle visited the Paste Studio earlier this year where she treated her internet audience to four songs from the record: driving roots number “Take The Journey,” the suspenseful “Messed With My Mind,” the melancholic and melodic “Sleepwalking” and “Light Came In (Power Went Out),” undoubtedly the album’s centerpiece and one of the most beautiful folk-pop blends in Tuttle’s catalogue. —Ellen Johnson

8. Angelo De Augustine: Tomb

8. Angelo De Augustine: Tomb

Few artists can quiet a room quite like Angelo De Augustine. Of the small handful of times I’ve had the chance to catch the LA-based singer-songwriter live, I’ve been struck by the intimacy of his music; from his hushed whisper-vocals to the gorgeous fingerpicked acoustic guitar, he can make a music venue feel like a living room, demanding the audience’s full attention by simply refusing to raise his voice. When the news of Augustine’s new record, Tomb, hit, it was announced that he was working with Thomas Bartlett aka Doveman, a renowned musician and producer who helmed recent records by St. Vincent, Rhye and Glen Hansard. If a lot of why Swim Inside the Moon was so heartbreakingly striking stemmed from its rough and lo-fi recording, how would a studio-produced release even remotely capture this same closeness? By and large, Bartlett’s cleaner mix works wonders for De Augustine. With cleaner vocals and an emphasis on a variety of instrumentation, Tomb is more direct than anything De Augustine’s released prior, while remaining as nostalgic and longing as ever. Evolving as an artist is tough work; the constant pressure to find the right balance of growth and experimentation without losing one’s initial identity can drive the most ambitious of artists insane. By adding cleaner production, synth and string flourishes alongside poppier and catchier refrains, De Augustine largely hits the mark on Tomb. With a few curveballs thrown throughout, the warm and comforting lull of Swim Inside the Moon is long gone, replaced by a fascinating record that updates his prior work without losing any of its intimacy. —Steven Edelstone

7. Florist: Emily Alone

7. Florist: Emily Alone

There is transformative power coursing through the 12 songs on Emily Alone, the new album from indie-folk project Florist. It’s not loud or showy or self-serving or generous. It’s just there, simple and plainspoken, waiting to be engaged and willing to move through anyone who needs it. Presumably, that’s what happened to Emily Sprague, the Los Angeles-based singer-songwriter named in the album’s title. Last winter, she wrote and recorded Emily Alone during a period of isolation and personal reflection spurred by the unexpected death of her mother and a move across the country, away from her collaborators in Florist (the band’s home base is still listed as New York on their Bandcamp). On Emily Alone, Sprague strips down her songs to their barest elements, leaving only her voice, words and plucked acoustic guitar (plus an occasional exception) to carry the message. What’s left is not just bedroom-recorded confessional music, but pure introspection, confusion, revelation and emotion rubbed raw and exposed to the world. These songs are not sad so much as they channel the ebbs and flows of life lived inside a human brain with startling accuracy. Perhaps you have to be in the right place—emotionally, spiritually, spatially or whatever—for Emily Alone to impact you fully. But if you’re there, you’ll feel it. And if you’re not there, that’s okay. When you’re ready, Florist will be there waiting for you. —Ben Salmon

6. Laura Stevenson: The Big Freeze

6. Laura Stevenson: The Big Freeze

Despite the fact that she’s not nearly as well known as she should be, Laura Stevenson continues to make music that can stop your heart. In that regard, her latest is arguably Stevenson’s most adept album. The Big Freeze trades the raucous guitars and bold hooks of her earlier work for subtler musical textures on songs that open into more expansive interior worlds. The album as a whole sorts through a host of complicated feelings about family, the thin line between inter- and codependence, and trying, if just for a minute, to silence fear, shame and doubts and feel OK as oneself. Stevenson lays out a portrait of dysfunction on “Hum,” glimmers of guitar framing her precise, quiet vocals as she builds tension with such stealth that it comes as a surprise to find you’ve been holding your breath. “Hawks” is a wistful waltz-time evocation of a happier period, while the next song, “Big Deep,” feels like its emotional counterpoint as Stevenson describes a particularly fraught moment. She harmonizes with herself on both, accompanied by barely-there guitar, the low moan of a cello (on the former) and deep, distant piano (on the latter). Album closer “Perfect” feels like Stevenson has reached an equilibrium of sorts, balancing past with present, and emotional turmoil with a brittle sense of acceptance. There’s tenacity there, too: “I’ll be alright by myself tonight,” she sings in the first and last lines of the song, a folky number with acoustic guitar and multi-tracked vocal harmonies. It’s clear that she means it, and even if being genuinely alright takes more time, more effort, more emotional energy than she ever would have wanted, it’s equally clear that she is determined to make it true. —Eric R. Danton

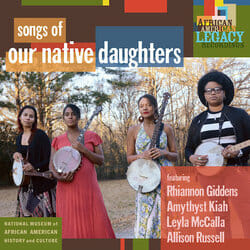

5. Our Native Daughters: Songs of Our Native Daughters

5. Our Native Daughters: Songs of Our Native Daughters

“This album confronts the ways we are culturally conditioned to avoid talking about America’s history of slavery, racism and misogyny,” writes Rhiannon Giddens in the extensive liner notes that accompany Songs of Our Native Daughters, the debut from a supergroup comprised of Giddens, Tennessee solo artist Amythyst Kiah, Haitian-American multi-instrumentalist Leyla McCalla and Allison Russell of Po’Girl and Birds of Chicago. This statement of purpose unites the album’s 13 historically-attuned songs, which draw from 17th, 18th and 19th century musical and literary sources in addition to the musicians’ own histories of discrimination, trauma, resilience and community. But Giddens’ mission statement can also be read as a reflection on the blurry-edged genre that’s come to be known as “folk,” “roots” or “Americana” music in recent years. These signifiers should, in theory, be capacious and inclusive; technically speaking, they refer to little more than the presence of acoustic stringed instruments in a piece of music and some aesthetic or thematic connection to America’s past. Songs of Our Native Daughters is not only a musical project but also a scholarly one, delving into historical archives and unearthing source material that includes slave narratives, family genealogy, abolitionist poetry and the Briggs’ Banjo Instructor of 1855, the earliest known minstrel banjo tutorial. In every case, the creators lift a scrap of history—a couplet, a melody, a first-person account—and follow it like a clue, finding voices for silenced figures and contemporary analogues for centuries-old concerns. —Annie Galvin

4. Joan Shelley: Like The River Loves The Sea

4. Joan Shelley: Like The River Loves The Sea

Joan Shelley was kind enough to include a thesis statement with her new album Like The River Loves The Sea. It’s the first track, “Haven,” and its only verse goes like this: “A haven woven with warm colors / A woolen place to rest your head / And a light comes in / Forms and binds you / To mold and carry you this long way to go.” Shelley isn’t just the singer of the song. She is that light. This was already established back in 2017 by Paste’s review of the Louisville-based folk-singer’s previous (self-titled) full-length: “Shelley’s light is absolutely irrepressible.” In fact, it glows even brighter on Like The River Loves The Sea, her sixth LP. Where Joan Shelley and 2015’s Over And Even occasionally dimmed Shelley’s songs with shadowy production or dusky arrangements, the new album’s dozen tracks feel more confident and out in the open. Take, for example, “Coming Down For You,” a spirited song of devotion driven by a repeated guitar riff that seems to flicker like a flame in a steady breeze, featuring the world-class backing vocal work of Bonnie “Prince” Billy, aka Shelley’s fellow Louisvillian, Will Oldham. He shows up later, too, on “The Fading,” a delightfully lilting ode to the natural world: Springtime light, a muddy river, winding vines and rising seas dot the track, which is not only the best on the album, it’s also a centerpiece of sorts. “Oh Kentucky stays on my mind / It’s sweet to be five years behind,” Shelley sings, poetically capturing the alluring, unhurried pace of life in her home state. —Ben Salmon

3. Jessica Pratt: Quiet Signs

3. Jessica Pratt: Quiet Signs

The worst assumption you can make going into Jessica Pratt’s Quiet Signs is that there won’t be much there, that minimalism isn’t for you. Knowing the folk singer/songwriter’s aversion to bells and whistles (and taking into consideration the album’s telling title), I myself feared a hollowness, but I was delighted to find the singer/songwriter somehow brings a maximalist energy to a record so subdued you’ll refrain from speaking during its quivering 27 minutes, for fear of disturbing the peace. Quiet Signs is a convincing argument for simplicity. Pratt has a very, very restrained way of supplying strength and relief during our hectic moment. Her songs are so quiet they almost don’t even exist, but maybe that’s how we need to feel for just a moment—like we’re just air. These tracks aren’t immediately satisfactory. They emit tranquility only if you’re willing to devote your full attention—and perhaps repeated listens. In under 30 minutes and in just nine songs, Pratt produces a warm, bewitching alternate dimension—but not the kind you fall into in a nightmare or thriller. The universe she’s fashioned for herself is more paradisal. And if you take a moment to find a quiet space and just sit with this record’s hollow parts, embracing them for the condensed elements they are, you might just find your own slice of heaven. —Ellen Johnson

2. Bedouine: Bird Songs of a Killjoy

2. Bedouine: Bird Songs of a Killjoy

Isolation can be both enjoyable and insufferable. Azniv Korkejian (aka Bedouine) explores both kinds of confinement in these Bird Songs, first the frustrating loneliness of “two people never getting together” on swirling album opener “Under the Night,” then the startling freedom of separation on “One More Time,” where she basks “on an island with no one else around.” On “Bird,” she warns “that it’s you against the rain” and dotes on some sweet, flightless creature before leaving it alone to “sing.” Early in the record she mournfully quips, “You love how much I love you / when you’re gone.” All these verses point to a complicated, ever-changing relationship with space and separation. While many of these songs are concerned with flying solo, Korkejian is still an expert on “Matters of the Heart,” a sly and jazzy tune that uplifts side B of this record. When she sings, “Call me like a phone / Just ring to me, baby” Korkejian sounds like the same woman who said, “I like watching people make out to my songs so I encourage consensual… anything, really,” at a Bedouine show earlier this year. She who values alone time can still yearn for company. I treasure both, and I would like to curl up inside Bird Songs of a Killjoy and live there forever. —Ellen Johnson

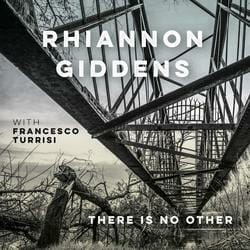

1. Rhiannon Giddens & Francesco Turrisi: there is no Other

1. Rhiannon Giddens & Francesco Turrisi: there is no Other

On her newest endeavor, the album there is no Other (out now on Nonesuch), former Carolina Chocolate Drops frontwoman and banjo whiz Rhiannon Giddens, along with the Italian multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi, tracks the movement of people—and their music—across cultures and centuries, particularly in regards to their respective areas of expertise: Giddens knows inside and out the African American influence on roots, acoustic and old time music; for Turrisi, it’s a deep knowledge of Arabic music and its imprint on Europe and beyond. The album is grounds for a smaller world, a beautiful narrative convincing us of our similarities, not our differences. The stories in these songs can act as hymns, folktales or dispatches from some lost time or place, but it’s really in the instrumentation where the album’s deepest messages—a condemnation of “othering,” the social practice of ostracizing those considered outsiders, and a campaign for the similitude of human experiences—come to light. If instruments from different parts of the world can work together so seamlessly, why can’t people? —Ellen Johnson

Listen to our Best Folk & Bluegrass Albums of 2019 playlist on Spotify right here.