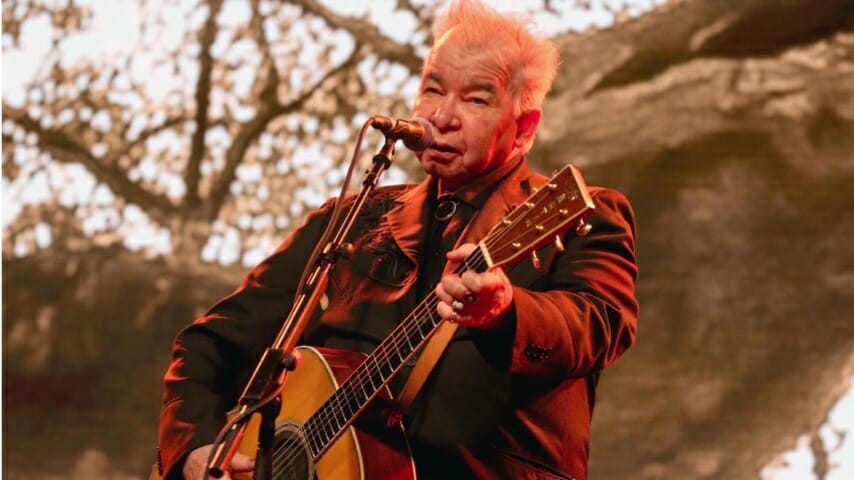

Remembering John Prine: The Droll Voice of the Common Man

Photo by Gary Miller/Getty

John Prine, who died Tuesday of Covid-19, once claimed that his three main influences were Bob Dylan, Hank Williams and Roger Miller. Like Dylan, Prine was a Midwesterner who got his start strumming an acoustic guitar and compensating for his small, nasal voice and melodic well with lyrics that made your head snap around and say, “What was that?”

Unlike Dylan, however, Prine didn’t write long, sprawling lines with the flamboyant metaphors employed by bohemians arguing philosophy late into the evening, Prine wrote compact, down-to-earth lines using the common-sense aphorisms traded by blue-collar workers on their lunch break.

These were the same people Williams provided a voice for—folks who’d left the farms of Alabama and the mines of West Virginia to work at factories in Chicago and Baltimore and to send their kids to the state university or the civil service.

Prine was one of those kids and he twisted their stories enough to yield the absurdist humor that Miller was so brilliant at. Then he twisted them again to go where Williams and Miller had never ventured—to give his stories endings closer to face-slapping reality than to the comforts of Music Row. If Dylan specialized in the ironies of the overeducated, Prine did the same for the underemployed.

When this short, pudgy Chicago mailman released John Prine in 1971, the first five songs on that debut album were “Illegal Smile,” “Spanish Pipedream,” “Hello in There,” “Sam Stone” and “Paradise.” It was perhaps the strongest start to a singer-songwriter’s career in history, but it was the fourth song that made Prine’s reputation. While the bodies were still being counted in Vietnam, Prine wrote “Sam Stone,” the war’s best song, by doing what he did best: creating a specific character, putting him in a specific setting and letting the story unwind in short, terse lines.

It’s significant that Prine’s Vietnam character was no protester or Indochinese peasant but rather a working-class kid from Chicago, a G.I. who started shooting heroin to ease the pain of his knee injury and then couldn’t stop. The song’s crowning touch, though, was the chorus, which was sung by Sam’s young daughter, who couldn’t understand why all the money disappeared down “a hole in Daddy’s arm” and why life wasn’t like the sweet songs on the radio. Those songs promised everything was going to work out by the final chorus, and that wasn’t happening to her father.

Prine didn’t write that kind of song. Though his songs were covered by artists such as Bette Midler (“Hello in There”), Johnny Cash (“Unwed Fathers”), John Fogerty (“Paradise”), Bonnie Raitt (“Angel from Montgomery”), Swamp Dogg (“Sam Stone”), Kris Kristofferson (“Jesus Was a Capricorn”) and Miranda Lambert (“That’s the Way the World Goes ‘Round), Prine’s were not the sugary songs of pop or country radio; they were droll, deadpan observations on quotidian life, stories so understated that you often had to hear them twice to get the joke—or the knife stab of fate.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-