Haggard v. Jones: One of the Great Bar Arguments of Our Time

If you want to know somebody, ask, “Beatles or Stones?” Whichever they choose will reveal certain truths. Those who pick the Beatles tend to be thinkers, more taken with detail, curious about the far-flung and engaged in the minutiae. The ones who claim the Stones lean to the visceral; they’re hard-hitting, gut-driven, earthy and often seeking pulse-pitching thrills. One thing, though, is consistent: each is passionate about their preference.

Second only to the great Beatles/Stones debate is the Haggard/Jones face-off. Its heated rhetoric devolves into flat-out name-calling when the issue’s raised in any Saturday night beer joint, honky tonk or roadhouse with a decent selection of classic country on the jukebox. It’s the kind of back and forth that goes long past closing time.

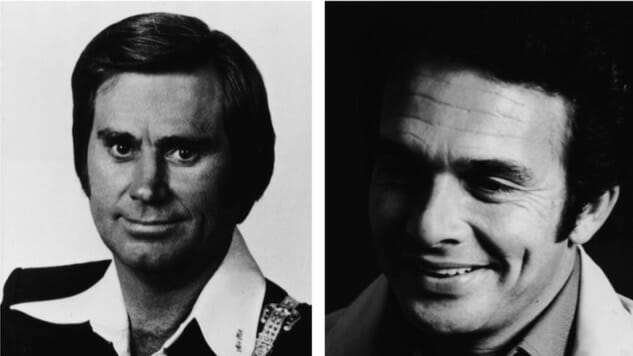

In this corner, George Jones, the duck-tailed Texas caterwauling ’50s Starday Records sensation who could set a song on fire—and recorded arguably the greatest country song ever with 1980’s “He Stopped Loving Her Today.” In the other, Merle Haggard, a hawk-eyed Bakersfield ex-con who exhaled honky-tonk velvet with a pure blue-collar bent, who defined patriotism and swagger with 1969’s anti-counter culture anthem “Okie From Muskogee.”

On one hand, the Possum’s lack of emotional restraint makes him perhaps the most full-tilt vocalist of all time, certainly compelling as the definitive country artist of our last 60, 70 years. To hear him lurch into “I’m Ragged, But I’m Right”—voice pole-vaulting up to the final line of the verse, or dropping down into a deep bass register on the chorus—or slide from note-to-note for a single syllable on the James Taylor-written tribute “Bartender’s Blues” is to hear a man whose prowess as a singer defies gravity and logic.

He Evel Knievels “White Lightning” and “The Race Is On” with a brash hillbilly brio that almost swerves out of control when the tempo surges, bumping up and over notes as the songs hit another peak. When he opens the taps of full lament—as he does watching the cold jarring truth go down on the second floor across the street in “Window Up Above”—it is a gush of anguish, overwhelming and emotional chaos.

In ache, Merle Haggard never gets so rent. When things are hard, he is stoic, occasionally vulnerable. “Shopping for Dresses,” laden with a creeping bass and the silkiest strings, finds the oaken baritone rising from his loneliness by taking in all the sartorial colors and styles for the woman he’s yet to find, while the buoyant, gut string-driven “If We Make It Through December” lets philosophy temper the tough luck the out-of-work father/narrator needs to keep hope and dignity for his hard scrabble situation.

Haggard is never merely downtrodden. When his fighting side activates, without losing his cool, you know it’s on. Occasionally feisty (there’s no confusion about “Think I’ll Just Stay Here and Drink”) or straight rejecting—the “no thanks” Western swing of “Big City”’s smooth- as-good-moonshine declaration “take your retirement and your so-called social security…”—Haggard is nobody’s fool. When he throws down, duck.

“Working Man’s Blues,” all train-beat shuffle and railroad tie percussion, is a stout fist-pump of solidarity for those putting in the overtime with its “I ain’t never been on welfare, and that’s one place I won’t be…” His justifiably riled patriotism ignites “Fighting Side of Me” with its taunt of “If you don’t like it, leave it” like a straight fist to the jaw.

While Haggard is regarded as the people’s poet, Jones’ songs have an elegance that imbues jukeboxes with elevation. “Good Year for the Roses,” also the single from Elvis Costello’s 1982 countrypolitan Blue, paints a cast-off lover viewing the remains over swollen strings: “I can hardly bear the sight of lipstick on the cigarettes there in the ashtray, lying cold the way you left ‘em, but at least your lips caressed them while you packed/ A lip print on a half-filled cup of coffee that you poured and didn’t drink/ but at least you thought you wanted it is more than you can say for me.”

Rarely is Jones a creature of introspection—rather pure immersion in sensation, emotion, moment. “If Drinking Don’t Kill Me (Her Memory Will)” is all pain no waiting. His voice wrings every measure of agony from the tale of a man who can’t drown what’s haunting him.

Haggard thinks. For all the barroom reference—“Swinging Doors” or “Tonight The Bottle Let Me Down”—“Goin’ Where The Lonely Go” and “A Place To Fall Apart” suggest the tavern as temple of reflection more than a high time memory-numbing hub. With a few spilled piano notes, “Mis’ry & Gin” lives with the ghosts, trying to conjure what was sweet and face imploding one’s happiness in a world of folks just like him.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-