The Disappearing Art of Bar Band Music

A Curmudgeon Column

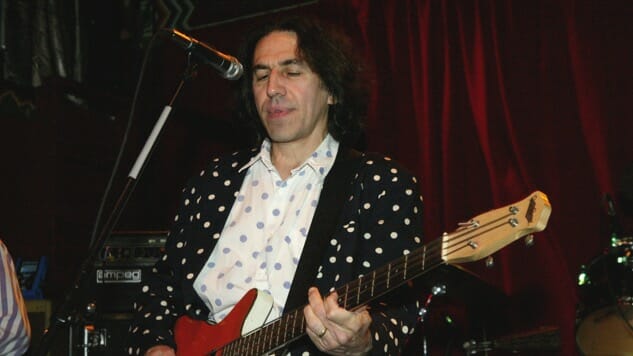

Photo by Phil Han/Getty Images

The 1978 album NRBQ at Yankee Stadium boasts a delightful visual joke. The title suggests that the band had been documented playing for 50,000 screaming fans, much as the Beatles had at Shea Stadium 13 years earlier. But the album cover is a photo of the cavernous ballpark entirely empty except for four tiny figures sitting behind the first-base dugout. On the back cover those figures are spied through a pair of binoculars and revealed to be Joey Spampinato, Al Anderson, Terry Adams and Tom Ardolino of NRBQ.

The joke was deepened by the fact that NRBQ was still playing bars a dozen years into their career—and would still be doing so three decades later. Critics took to calling them “the world’s best bar band,” a label that was both a blessing and a curse. Sure, everyone wants to be the best at something, but no band wants to be consigned to a career in noisy, poor-paying barrooms.

That fate was especially galling to a band like NRBQ, which wasn’t so different from the Beatles after all. Bassist Spampinato wrote and sang lovely McCartneyesque ballads. Guitarist Anderson played lead and wrote songs as if he were channeling Carl Perkins, just as George Harrison had. Keyboardist Adams was the focal point; his Lennon-like irreverence kept pushing boundaries, though he drew more from Sun Ra than from Bob Dylan. And Ardolino was the Ringo-like drummer.

But spending your life in bars rather than stadiums affects how the music comes out. The Beatles scaled their music to conquer the world, while NRBQ scaled theirs to entertain a barroom full of bohemian and working-class drunks. As a result, their lyrics were more down-to-earth; they were more likely to extol the pleasures of “Ridin’ in My Car” than to speculate on how many holes it takes to fill Albert Hall. They were more likely to record in the studio as if they were playing in a club: no backwards tapes or string quartets, just bass, guitar, keys and drums bashing out insanely catchy tunes.

The bar-band life encourages two healthy tendencies: a willingness to embrace multiple genres and an unbridled sense of humor. This music shouldn’t be confused with garage-rock, for garages are as different from bars as bars are from stadiums. Garage-rock is all about blowing off steam and venting pent-up feelings, while bar-band music is all about keeping a crowd in close quarters laughing, dancing and drinking. Playing for a close-up club audience yields a very different kind of music than playing for imaginary listeners in a garage or a faceless, far-off audience at a festival.

Back when they were still a bar band in Hamburg and Liverpool, the Beatles covered Chuck Berry’s R&B, Gene Vincent’s rockabilly, the Olympics’ doo-wop and Nat King Cole’s pop crooning, just as NRBQ would later cover Thelonious Monk’s jazz, Johnny Cash’s rockabilly and Big Joe Turner’s blues. The Beatles knew how to make audiences laugh with songs such as Fats Waller’s “Your Feet’s Too Big” and Carl Perkins’ “Lend Me Your Comb,” just as NRBQ could with “Howard Johnson’s Got His Ho-Jo Working” and “Crazy Like a Fox.” The Beatles left the bar-band phase of their career behind, but NRBQ never has.

That’s a good thing, because we listeners need both the grand ambitions of stadium music and the earthy intimacy of barroom music. No one did the former better than the Beatles, and no one has done the latter better than NRBQ. The proof is on the recently released NRBQ box set, High Noon—A 50-Year Retrospective. All five CDs showcase the underrated pleasures of bar-band music, but discs three and four, which concentrate on the classic Spampinato-Anderson-Adams-Ardolino line-up, are bar-band music at its best.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-