Finding Hope in the Darkness of Barry Season Two

Barry's internal strife is all too familiar.

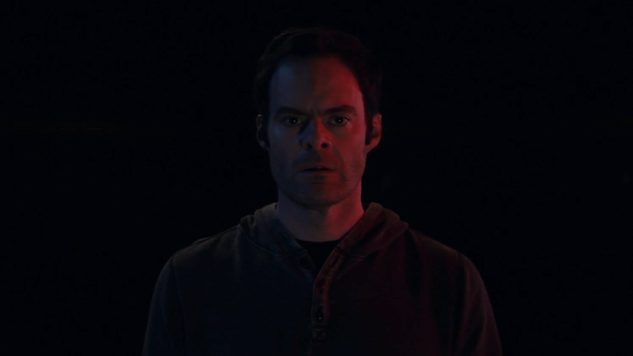

Images via HBO

Season Two of HBO’s breakout hit Barry is both larger and more intimate than the show’s first season. Stakes are low then they are high, then said stakes are set aside only to be brought up again at the most inopportune possible moment for each character involved. Barry understands that in reality not every day hangs on a knife’s edge, but some days you just find yourself getting stalked by a near-otherworldly 11-year-old karate master. Most importantly, Bill Hader and Co. are fully and intimately aware of the human psyche, how it fractures, heals itself and fractures again. The walk into darkness is not a one-way path, it happens at any and every direction. And it can be cyclical.

In the first episode of Season Two, Hader’s Barry Burkman (or Block, if you are in the talent world) emerges from the darkness. He looks like a new man: fresh, clean and, most importantly, happy. Secure, even. He’s found his purpose in acting, a love in Sally (Sarah Goldberg) and a father-like figure who, unlike Fuches (Stephen Root), takes Barry for who he wants to be, not who he really is underneath the flesh and sinew of the human figure. Henry Winkler’s Gene Cousineau is the mentor Barry needs. Yes, he may be brash and he may love money, but most importantly he is grieving due to Barry’s actions. Season One of the series ends with Barry seemingly killing off the last tie to his darkness, as Detective Janice Moss (Paula Newsome) parts ways with this world by way of a gunfight with Barry. She loses. Barry is free. His darkness is buried and his light is set free—until it isn’t.

Eventually, that buried self comes back out. Barry kills again—no, he murders. It builds to a crescendo in the final episode of the season, where his face contorts into a bestial snarl as he rains death and ruin on anyone standing in the way of his ultimate target. It ends with Barry once again becoming one with his darkness, quite literally. The final shot of Season Two sees him walking, gun in hand, into a pitch-black hallway. His burden has won, his aspired self seems to be as dead as the bodies he’s filled with bullet holes and his buried, tumultuous past is now his present.

And yet, despite the augmented violence, Barry grappling with his internal darkness as his flaws fluctuate between both internal ruin and external rage is relatable. No one in Barry is perfect, and the past plays a key role in many characters lives in Season Two. Sally’s abusive ex invades her present happiness, Gene Cousineau is in the bowels of grief and even NoHo Hank (Anthony Carrigan) finds some time for reflection. But it is still Barry that I find myself relating to the most. His ruminations over past acts and present flaws are porous—they flow into and through one another until Barry’s present becomes an echo of his past.

From the ages of 18 to 20 I struggled with an eating disorder. Since then, I’ve recovered (whatever that means), but the road to recovery is a bumpy, pothole-ridden highway with no exits. Every day, I think of the person I was during that time of great pain and flux, and how what I went through still informs almost every action I make today. From being medicated for both depression and anxiety to semi-regular meetings with a nutritionist, my life now is as much informed by my past as it is with my desire for a better present and future for myself, my body and my mindstate. Yet like Barry, I still find myself grappling with my darkness. I mean, I am not a hitman in the throes of untreated PTSD, but I can never trust how I view myself in a mirror. I’ve only recently come to terms with the fact that it is okay to dress in clothes that aren’t two sizes too big for me, and it is okay to enjoy food (though I’m still working on that last part).

Also like Barry, I find that my internal struggle with darkness becomes externalized in various ways, most of them unproductive. For a time, I’d weigh myself every morning until I realized that I probably shouldn’t have a scale in my house. That little square that told me a number—a number always too high for my distorted psyche—was just another way of my past eating disorder externalizing itself. I got rid of the scale; “I’m better,” I told myself as I dumped it into the trash can. But will I ever be better? Barry asks himself this question a lot, and he externalizes it to others in various ways. He is always fishing for the right answer, the answer that tells him everything will be okay.

I still find myself doing many of those same things. Like Barry, I sometimes seek validation that I am “okay” and that I am “better.” But the truth—the reality of my situation (and Barry’s)—is never as easy as a binary answer. Yes, I am better in some ways. I am healthier than I have ever been, but I still can’t look in mirrors, hardly appear in photos and probably workout far too often. Being better doesn’t always mean that I am okay. Barry stops killing, for a time—he is better, cleared of his past, or so he convinces himself.

Then his past comes knocking.

My time with an eating disorder has forced me to reconcile with my past, to rebuild burned bridges, to accept the fact that I transferred colleges because of it, lost friends and important connections because of it. But I refuse to let it define me, to shape me. Yes, it is one of the stormy winds that steers my sails in all directions, but I’ve gotten better at turning my darkness—my deepest and most dangerous flaw—into a part of my past that somewhat defines my present. Unlike Barry, so far, it does so in a healthy way that is good for me and those around me. There are bumps in the road, and I will definitely always be in a state of recovery, but I am clinically healthy. My psyche may be irreparably damaged, but I can live with that; I have gotten to the point where I am strong enough to accept that and to work through it.

Barry hasn’t. He has allowed his past, his darkness, to remain circular. I’d like to believe I’ve broken free of that circle—that snake constantly eating its tail until it reaches the head—but only time will tell. As for Barry, it looks like the snake has already eaten its head, as he has become a walking embodiment of his past and a distant shadow of his desired self. Only Season Three will tell us if Barry’s darkness remains circular, if he is doomed to repeat the past and constantly be asked to answer for the errors of his ways.

But unlike Barry, himself, I am pulling for him to rise above his fractures. His fractured self can be glued back together. Season Three could be focused on Barry going through PTSD therapy, coming to terms with himself, maybe doing jail time, but it won’t be. Audiences want their lovable and sometimes hateable assassin, and maybe Barry wants that, too (or at least, that would make for compelling TV, right?) But television is not reality. While I see the darkest and most ashamed parts of myself in Barry and its themes, I choose to believe that ultimately the show is a coda for self-betterment in the face of absolute darkness.

Cole Henry is an intern at Paste and an avid taco enthusiast. You can follow him on Twitter @colehenry19