Why Alex Gibney’s Rolling Stone: Stories From the Edge Isn’t a Party Worth Being Invited To

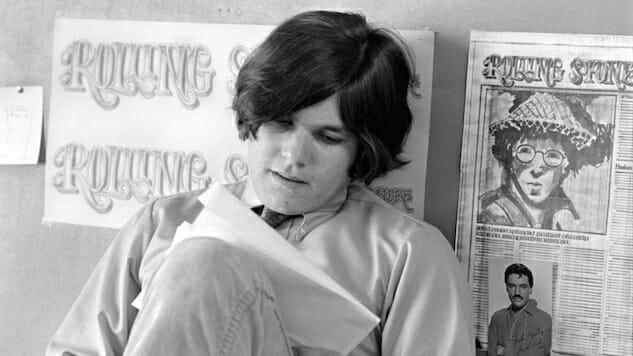

Photo: Baron Wolman/courtesy of HBO

Recently, I was laying some smartphone scare-stats on my 14-year-old, Grace. “They say that teen pregnancy is through the floor since 2012, you know.”

“That’s a good thing, right?”

“Well, they say it’s because no one has real relationships anymore. They just sit at home and text each other.”

Grace uncomfortably put her device in her pocket.

“And you know those kids who have such stratospheric anxiety that they can’t even go to school?”

“Because smartphones?”

“So they say. Kids are growing up with this paralyzing social anxiety, because other kids are creating these curated personae and posting selfies from cool parties everyone else seems to have gotten invited to, and…”

“Huh.” That one touched a nerve—I knew it would. See, that was how I used to feel when I read Rolling Stone. The insider smugness of that rag hit my limbic system like a bomb. “We are the cool kids, neener, neener,” it said.

Eventually, I figured it was me. I mean, I’d grown up wanting to be an A-list vocalist and that hadn’t happened. It was the 1980s. I was a great singer and a great lyricist, but I knew I’d never be able to play guitar like Joni Mitchell or Prince, or singlehandedly write artsy-awesome songs like Bowie or Peter Gabriel—I didn’t have the skill set to own the room without someone behind me, and that someone never appeared. In my mid-20s, I ran afoul of half a dozen also-rans with varying degrees of talent and remarkably monstrous egos, culminating in a situation with an out-to-pasture producer with a wall of gold records in his office in Laurel Canyon, who wanted to make me his big comeback act. He offered me a large amount of cocaine and told me I’d need to do the blow, blow him, and pay out of pocket for the demos. That did it. I knew I was never going to be like the people I read about in Rolling Stone. I didn’t have the temperament.

Eventually I became glad I didn’t have the temperament.

I confess I found it hard to sit through HBO’s Rolling Stone: Stories from the Edge. And I’d been wrong. The issue wasn’t that the magazine made me feel like everyone had been invited to the awesome party but me. The party was the problem. The party was insufferably boring.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-