YOU Is Problematic Because of Us

YOU is low-hanging fruit for criticism, but the power of what makes it either very good or bad connects back to the rot within our society.

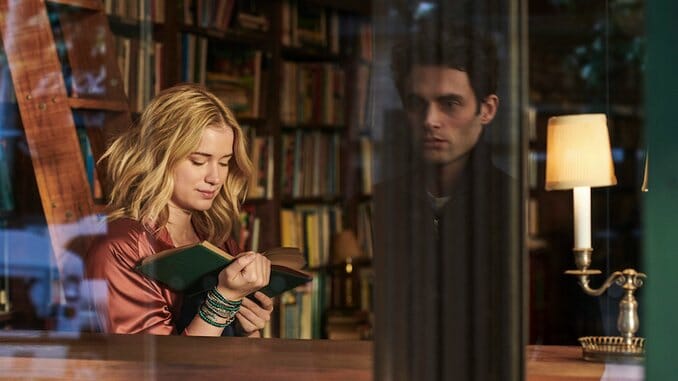

Photo Courtesy of Netflix

I initially followed YOU at a distance, not directly engaging with the show for some time, but found it addicting to refresh my feed and watch new tweets trickle in. Looking back, my behavior mirrored Joe’s. At the time, I thought of myself as a scrupulous hater, pacing back and forth over the internet for bad takes—but I resisted responding to supporters of the show online. The Internet felt like a minefield for me, a place of danger. The reason I never used social media and I stalked YOU was the same: I had been stalked personally.

I justified my contempt for the series after seeing the initial response. Judging by the trailers and the fan response, YOU appeared to spin a false narrative of intimate partner violence: it could be scary, but more so sexy. For audiences watching the teaser, the trailer operates as a feisty love bite. Shots of Joe (Penn Badgley) perpetrating crimes meet sultry moments of him with Beck (Elizabeth Lail) engaging in risque (even public!) sex acts. Without a trained eye, YOU seemed par for the course, a “sex sells” TV show. In one respect, YOU’s sultriness rings as an inevitability for a show conceived on Lifetime. But as I resolved to watch it further, troubled by the treatment of its central conceit—even more disturbed by what the show got right about stalking—I realized that YOU’s classification as a B-list TV show was connected to what made it infuriating and also, occasionally, calculatingly effective.

It took a considerable amount of time for me to complete the first season of YOU. Early on, I’d force myself to watch single episodes at a time, waiting for a painful amount of cortisol to flood my body as the plot plucked away at my triggers. I’d stall. I’d push deadlines back. But as I fully committed to watching the first season in its entirety, I noticed the most uncomfortable aspect of viewing YOU was this: Joe still inexplicably felt attractive. Even cutting through YOU’s satirical veneer—Joe’s embarrassing inepititude at sex, even murder—he had charm. This ate at me. I knew better than anyone that I should direct my ire at someone like Joe. Yet once I started to tug at the narrative strings that gave Joe this power, YOU’s truth-telling capacity snapped into place.

Is YOU a master document for understanding our own time? Yes, in that YOU acts as a blacklight in a filthy hotel room: it only shows under different lighting what was already there. YOU doesn’t pretend to put on the fancy airs of a prestige show, marketing its intelligence or panache. Instead, it simply winds up the premise of the show and sets it in motion. The audience’s reaction to YOU’s storyline simply reflects American culture’s valuation of romance, love, and sex. As Joshua Rivera from The Verge eloquently comments, Joe “benefits from decades of cultural attitudes that have worn away at the agency of women, of romance tropes that valorize the persistence of men in pursuit of a woman, and the gendered head games that give men the upper hand in most every interaction they have.” Viewers are primed to view relentless suitors as the romantic ideal. Decades of popular love stories’ male leads engage in similar dubious behavior as Joe: Twilight’s Edward Cullen looms over unaware Bella nightly in her bedroom, The Notebook’s Noah sends copious letters to no response, You Got Mail’s Joe negs his indie bookstore rival into a relationship. While I felt guilty about my reaction to Joe, it made sense. Our sympathies flow downstream in direction with the current of social power. Joe wins by playing the role of the house.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-