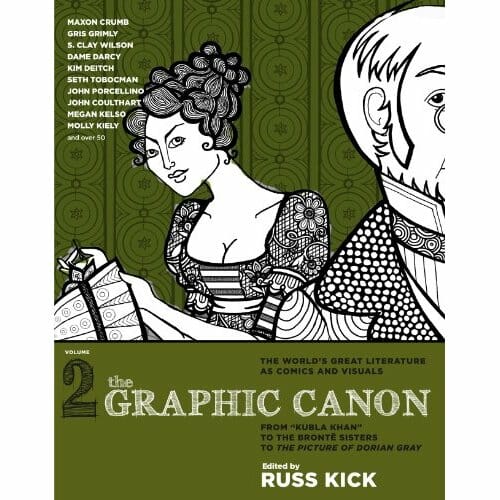

The Graphic Canon: Volume 2 edited by Russ Kick

History of the World, the Remix

There’s something seductive about an impossible project … and what would seem more impossible at first glance than The Graphic Canon?

In our age, the very notion of what constitutes “the canon” has been deconstructed and reassembled over and over. The idea of an anthology that encapsulates all of classic literature in visual form seems dubious at best.

So it’s unsurprising that the task falls to someone like Russ Kick, a former editor of books with titles like You Are Being Lied To and Everything You Know is Wrong, who seems to have gone from undermining one establishment to giving another one a makeover. The Graphic Canon (subtitled The World’s Greatest Literature as Comics and Visuals) still has one more volume to go, but it already stands as not only Kick’s most ambitious project to date but one of the most ambitious in the history of the graphic medium.

The title is a bit modest, actually. In selecting titles for adaptation, Kick often goes above and beyond the traditional Western body of literature. He includes some works usually left alone even in university classrooms. We saw this in the first volume, which started with Gilgamesh and ended in 18th-century France and included curios like Apu Ollantay, the only surviving work of native Incan drama.

That’s a hard act to follow. For much of Volume 2: From Kubla Khan to the Bronte Sisters to The Picture of Dorian Gray, we’re stuck with the Victorians and their contemporaries, beginning with a photo-realistic take on Coleridge and skipping through the 19th-century. The famous and familiar abound: See Heathcliff running over the moors! Behold Dr. Jekyll turning into Mr. Hyde! Witness the Ancient Mariner and Count Vronsky rubbing shoulders with Darwin and Rimbaud.

A few lesser-known works get attention, such as Fitz Hugh-Ludlow’s The Hasheesh Eater, a Mary Shelley B-side and a selection of the infamously macabre nursery rhymes of Der Struwwelpeter. For the most part, though, the thrill this time comes less in the discovery of new things than the anticipation for how such staples as Pride and Prejudice will be represented. True, it may be a bit of a comedown after the first book’s Popol Vuh and Hagoromo. But this also means more focus, with remarkably different views of the same era. We go from the hallucinations of the Romantics to the slave narratives of the American South, from Flaubert to Venus in Furs. Whittling down entries for this one must have been painful; Kick could easily fill three more volumes with adaptations from some of these prolific authors alone.

As with Book One, descriptions of all the different sights to be seen here could leave one asthmatic. Dave Morice gives us Whitman as a cosmic superhero, complete with cape and a giant ‘W’ on his chest. Shawn Cheng draws a hilariously jaunty version of a Brothers Grimm tale, reminiscent of Adventure Time. Dame Darcy provides delirious inky interpretations of Dickinson and Carroll, with wide-eyed characters scrunched next to swooping cursive letters. Oregon-based illustrator Pmurphy envisions Wordsworth as a bearded astronaut having psychedelic visions on a moon the color of an Easter egg. Elizabeth Watasin presents a hauntingly beautiful Jane Eyre in watercolors with cool blue hallways and roaring red flames.

Some of the best adaptations here (particularly John Coulthart’s atmospheric Dorian Gray) draw luscious inspiration from the styles of the period. Others, like John Porcellino’s minimalistic take on Walden or Mahendra Singh’s Ernst-ian Hunting of the Snark, find new stylistic avenues into the original while staying true to their spirit.

In a book full of such pleasures, two transcend.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-