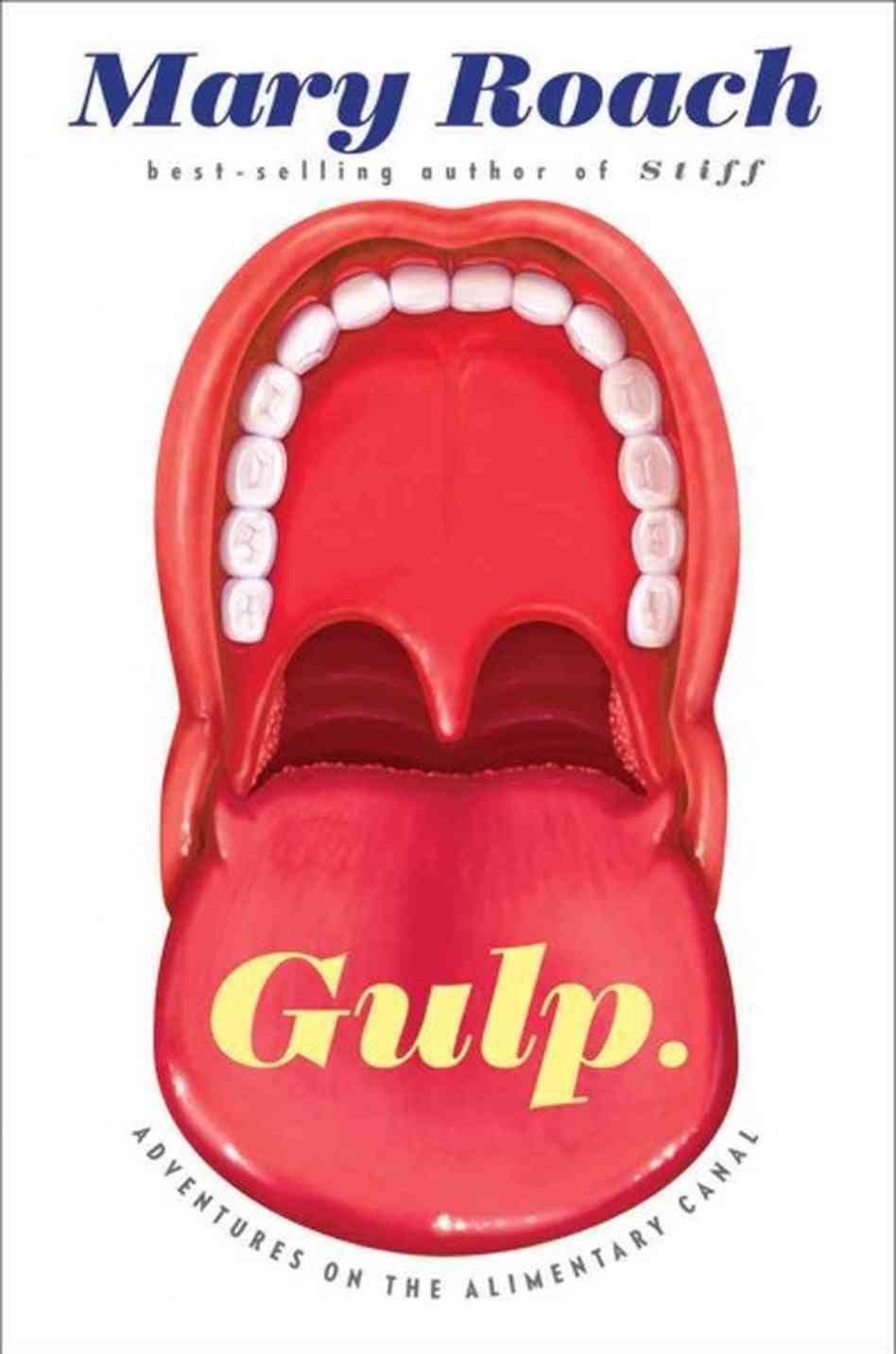

Gulp. Adventures on the Alimetary Canal by Mary Roach

Gut with gusto

For many of us, culture offers escape from the kind of bureaucratic drudgery so sharply lampooned by the likes of The Office, Dilbert and Office Space.

Holed up in cubes, we spend our days battling arcane procedures. We stare for hours at unblinking, backlit screens and stop only for bathroom breaks. We miss lunch. We bandy passive-aggressive emails thick with the latest hip euphemisms. By day’s end, the strain of hours spent slinging words the way assembly-line workers toss parcels brings temporary scoliosis. Not even the most expensive ergo chair can prevent it.

Perhaps in that brief pause between the job’s end and the instant we slip on ear buds for the commute home, we briefly yearn for the work we once imagined we’d grow up to claim. You know—jobs characterized by wonder, joy and movement.

Then the moment passes.

Mary Roach gives us all hope. In her latest book, Gulp, she leads the reader on a fast-paced tour of a most mundane workplace—the human gut. Nasal cavity to anus.

By turns, it fascinates, grosses out … and thoroughly entertains. I’m not sure whether I grimaced or guffawed more, but I’m still surprised no fellow BART passengers who shared my train as I read Gulp asked what on earth provoked such reactions from me.

Beginning with the nose and its pivotal role in taste, Roach makes her way from an olive oil taste-panel tryout (which she fails) to a Davis, Calif., research facility where she sticks her arm inside a fistulated cow. (A fistulated cow, Paste reader, is a cow with a permanent, surgically created hole in its side — generally done for scientific purposes, such as observation of the cow’s digestion.) Roach wishes to test the creature’s stomach capacity. Lest you think her a tomboy, she reports that her kitten heels and skirt gave the scientist accompanying her no end of amusement.

Moving further down the Golden State—and the digestive track—Roach interviews a central-California prisoner experienced in “hooping”—the practice of smuggling by rectum. She then concludes this … ah … course of research by observing a more beneficial anal additive: the fecal transplant.

Roach does not confine her tale to the present. We meet patriotic chewer, Horace Fletcher, who sought to improve WWI-era vitamin absorption by drastically increasing chew-per-bite rates. We huddle in the oversized home of the doctor who helped Elvis Presley cope with a constipation problem that probably killed him. (Yes, really.) Roach also reports on an ill-fated WWII attempt to increase civilian consumption of animal organs (feeding armies caused a meat shortage), and the dubious medical treatment that probably hastened President Garfield’s death.

Despite her stories’ sometimes lurid qualities—Roach seems to relish these—we always find a keen appreciation for a subject’s humanity. From a murderer who answers her most probing questions about the “prison wallet,” to the French Canadian trapper whose unsealed stomach wound linked him in a strange relationship with ethically challenged surgeon-cum-scientist William Beaumont, Roach never lets foibles overshadow dignity. Her trademark droll humor never lurks far below the surface, but the writer rarely introduces a source without providing some sense of personality. No matter how overlooked by most of the world or how misunderstood even by friends and loved ones, Roach’s sources never come off as boring.

She weaves this tale in such entertaining fashion that we forget Roach often tackles deeply obscure material. (One Dutch scientist she interviewed reported his unit will be closed after he retires.) More than once she references a medical article tracked down in a foreign language journal somewhere, requiring a translator. Intriguingly, Roach seems to prefer that her translators read documents aloud to her. Describing one account, from an Italian journal, of a 17th-century exorcism involving a holy-water enema, Roach reports that the story surprised even the translator.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-