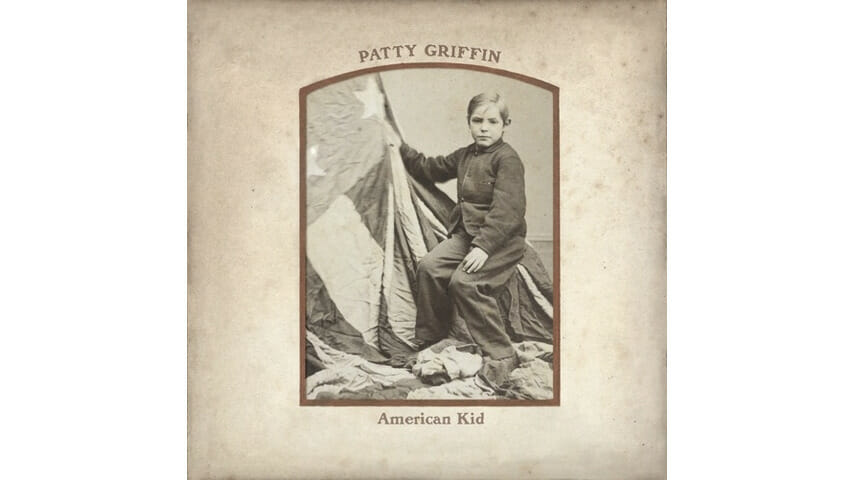

Patty Griffin: American Kid

With a bit of juke-joint loose blues strumming rising from a National guitar, Patty Griffin leans into “Don’t Let Me Die In Florida” with a tortured cry on what becomes a steamy track with a deep, surging pocket. A swampy exhortation, it is Appalachia gone gator with the songwriter’s fevered enjoinder given further urgency as her soprano swings from wide-open wail to silken surrender.

Death and displacement are certainly themes on American Kid. A more aggressive acoustic offering from the woman who rocked hard on Flaming Red, yet haunted on the spare folk of Poor Man’s House, American Kid creates its lean immediacy by enlisting the North Mississippi Allstars to strip down to their most organic.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-