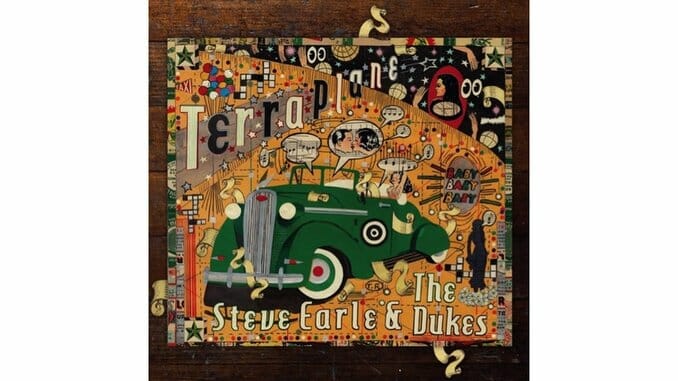

Steve Earle: Terraplane

On the randy, low-flying Stones-evoking “Go Go Boots Are Back,” Steve Earle scrapes the same guttural rock ‘n’ roll that made “Copperhead Road” so compelling. But as raw and guitar-stung as “Boots” is, Terraplane is a work of many textures.

Like The Mountain, Earle’s bluegrass project, this collection grounds in a single genre. Focusing on Texas and Chicago blues, Terraplane is a loose-grooved exhumation of Lightin’ Hopkins, Freddie King and Mance Lipscomb, artists Earle grew up on in San Antonio.

From the harmonica bleat on the swaggering “Baby Baby Baby (Baby)” to the jaunty “Ain’t Nobody’s Daddy Now,” Earle plumbs the carnal underpinnings of the blues: feasting on what can be, never mourning what’s done. It is frisky, with musicians thumping and plucking in what feels almost like a jam.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-