Where’s the Revolutionary Punch? Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me at 50

On May 23, 1958, Cornell University’s serene, gorge-encircled campus exploded in anarchic student demonstrations that presaged the widespread campus upheaval of the 1960s. Less disciplined and more inward-looking than the civil rights, antiwar and Black Power-focused demonstrations of the next decade, the Cornell protests erupted in response to the university’s crackdown on campus socializing—over the objections of students and faculty—and in particular the coeds-only curfew and restrictions on female students’ presence in off-campus apartments. Though the rules were introduced with some high-minded language about the university’s in loco parentis responsibilities, and the students’ obligation to “conform to the mores of the society in which we live,” eventually the administration admitted that they simply didn’t want students having sex.

Listen to Down So Long: A Richard Fariña Playlist here, and scroll to the end of the article for more information on the chosen songs.

Leading the protest was Cornell Daily Sun editor Kirkpatrick Sale, who 18 months earlier had exhorted his fellow students to shake off the blinders of student apathy and challenge the repressive status quo of Cold War America: “Cannot Cornell take its place with other people across the country in refuting the abominable notion of The Silent Generation?” Sale, who went on to write the definitive history of the 1960s student activist organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), seemed to know what he was doing, and approached the protest with a clarity of purpose that other students appeared to lack. What began as a fairly disciplined day/night protest (culminating in a group of female students publicly breaking curfew), eventually devolved into storming and egging the president’s house. Sale, along with three other students identified as leaders of the protest, was arrested and suspended from school.

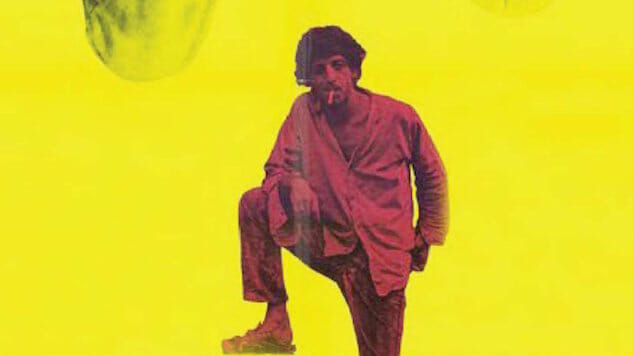

Also arrested was Sale’s one-time roommate: a wild-haired, strikingly charismatic, half-Cuban, half-Irish beatnik named Richard Fariña, who seems to have approached the protests with an audacious dose of ironic detachment. Fariña (a future novelist, folksinger, brother-in-law of Joan Baez and crony of Bob Dylan) might have joined the protest because he thought getting kicked out of college for civil disobedience would bolster his self-mythologizing résumé of improbable swashbuckling achievements, which already included drug smuggling, running guns for Castro and throwing bombs in Belfast; or maybe he took part because he envisioned writing about it one day. Whatever Fariña’s motivations at the time, he did indeed transmute the Cornell student uprising into fiction; the events of May 1958 play a prominent role in his novel Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, a cult classic published 50 years ago today. This week also marks the 50th anniversary of Fariña’s death. In a tragic demise that remains inseparable from his legend, Fariña died two days after his book’s publication, thrown off the back of a friend’s motorcycle while rounding a curve in California’s Carmel Highlands.

Hailed and promoted as a generation-defining “campus” novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me creates an indelible character and the often-phantasmagoric world that blossoms in and around his hopped-up mind. Unapologetically uneven and loose in narrative structure, but written with a relentless, frenetic energy, Been Down So Long picks up the story of “Young Gnossos Pappadopoulis, furry Pooh Bear, keeper of the flame,” at the moment Gnossos returns, talisman-stuffed rucksack on his back, “from the asphalt seas of the great wasted lands” to slip surreptitiously back into the fringes of campus life following an undetermined absence. Introducing an impressionistically rendered version of Cornell and its Ithaca, New York surroundings, Gnossos proclaims, “I am home to the glacier-gnawed gorges, the fingers of lakes, the golden girls of Westchester and Shaker Heights. See me loud with lies, big boots stomping, mind awash with schemes.”

Thus begins Gnossos’ by turns hyper-perceptive, drug-addled and deranged assault on the insular college world he once left behind and never entirely returns to, even as he reconnects with old friends; casually “bangs” coeds from whom he emphatically withholds himself; falls head-over-heels, frolicking-in-the-gorges in love with a girl in green knee-socks; finds himself duped into joining the protest fracas; and begins to see the matrix of sinister connections between his underworld contacts in Cuba and the on-campus power-brokers who seem inappropriately keen on his involvement.

Thus begins Gnossos’ by turns hyper-perceptive, drug-addled and deranged assault on the insular college world he once left behind and never entirely returns to, even as he reconnects with old friends; casually “bangs” coeds from whom he emphatically withholds himself; falls head-over-heels, frolicking-in-the-gorges in love with a girl in green knee-socks; finds himself duped into joining the protest fracas; and begins to see the matrix of sinister connections between his underworld contacts in Cuba and the on-campus power-brokers who seem inappropriately keen on his involvement.

All of this paranoid, conspiracy-theory stuff might seem pretty ridiculous. But Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me is a book that never insists on not being regarded as ridiculous. It deftly evades such hang-ups at some times and steamrolls them at others. Besides his monkey-demon, mandrill-at-the-window hallucinations (which apparently haunted Fariña in life), and comical quests for visionary enlightenment through mescaline and the mythic paregoric Pall Mall, Gnossos mostly keeps his head high above the fray by never losing his cool. Gnossos’ concept of “cool” is a doozy, encompassing broad swaths of Blaisdell, the reluctant gun-slinging hero of Oakley Hall’s genre-busting 1958 western novel Warlock; Sebastian Dangerfield, the feckless, untouchable anti-hero of J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man; and, of course, Fariña himself.

What makes Gnossos at times irresistible is the notion of exemption that springs from his concept of cool, his almost inhuman ability to avoid the earth-bound snares endemic to his life and times simply by standing apart from them. “I am invisible, he thinks often,” Fariña writes of Gnossos. “And Exempt. Immunity has been granted to me, for I do not lose my cool.”

It’s in this sense of exemption—as tenuous as it is enticing—that Gnossos most resembles Donleavy’s Sebastian Dangerfield. But because Gnossos is less self-satisfied, more fallible, more introspective, more questing, and more unfinished than Dangerfield—and only at times as much of a contemptible cad—his exemption seems both more appealing and more attainable.

The two books intersect stylistically as well. Though identified more with the experimental works of his close friend Thomas Pynchon, Beat writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, and counterculture and gonzo contemporaries such as Ken Kesey, Richard Brautigan, Hunter Thompson and Tom Wolfe, Fariña clearly owed a deep debt to J.P. Donleavy. Particularly in its meandering and expository first half (“Book the First”), rich in wildly funny character sketches, sex and drug-fueled mayhem, but mostly unencumbered by plot development, Been Down So Long rolls along with much of The Ginger Man’s gorgeously offhand poetic lilt. Fariña invokes Donleavy’s subtle stylistic innovations with snippet-length poetic asides and the subversion of traditional sentence structure through the frequent substitution of participles for verbs (a technique much less clinical than it sounds). As in Gnossos’ description of a Ravi Shankar raga absorbed as his mescaline high kicks in: “Sitar hunting a scale. Me on the tamboura, droning, wire in the wind, easy undulation. Soft.”

Fifty years later, decades after bigger-impact books and more fully realized careers defined the ’60s literary zeitgeist, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, for all its pleasures, packs little revolutionary punch. And the idea of a kid who takes some time away from college, sees a bit of the world, and returns to position himself outside the self-satisfied bubble of campus life looking in with smug amusement and hipster derision, is certainly not a new one.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-