The Get Down: Now That’s How You End a Season of Television

(Episode 1.11)

Netflix

Now that’s how you end a season of television.

All credit to The Get Down’s sixth episode, “Raise Your Words, Not Your Voice,” which served, by default, as the series’ mid-season finale: It’s a superlative piece of entertainment, and a successful distillation of the narrative’s underlying and overarching themes and subtexts. Staging the block party to end all block parties works in the favor of “Raise Your Words, Not Your Voice” as well as our own. But the party Books, Shao and the Kiplings marshal in “Only from Exile Can We Come Home” makes the one they throw in “Raise Your Words, Not Your Voice” look like the world’s most pathetic political rally (sans the xenophobia). Describing the alliance between the Get Down Boys and the kingdoms of DJ Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa as a “party” is grossly inadequate, even. Kingdoms, after all, have a way of falling. Just ask Rome.

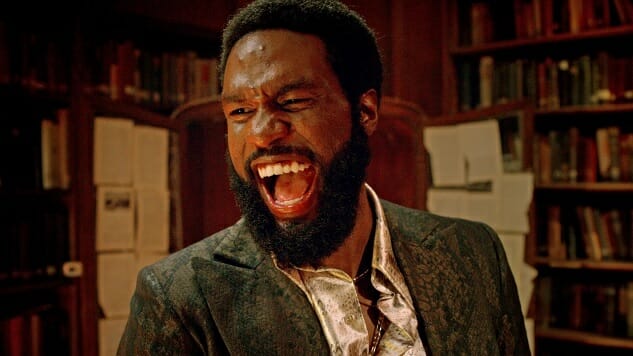

No, what the boys and the three hip hop gods accomplish in “Only from Exile Can We Come Home” is much greater and more meaningful than monarchy, something effectively immortal. The boys know it. Flash knows it. Herc knows it. Bambaataa knows it. Even Cadillac knows it, well enough at least that he decides to lay down his arms and go all-in on his record producing dreams (which, if the fates are kind, will give way to his astronautical dreams; if they do, hope for a spin-off, because watching Yahya Abdul-Mateen II dance on the moon would be nothing short of disco-strutting ecstasy). If The Get Down means to chronicle the birth of rap, and by extension the birth of hip hop as a culture (or, if you prefer, an aesthetic, and yours truly does indeed prefer), then this moment is the moment where hip hop’s identity as a unified and multi-disciplinary art form is truly, fully forged.

It’s a good moment. It might be the best moment the series has wrought to date, which is saying a lot now that we have all of Season One in our rearview. The Get Down has been out on a limb from its very first episode; by its very nature, it’s a gamble, a sprawling period tale built on a high count of interwoven plot lines, set against the backdrop of American turmoil and the rise of an entire genre of music from obscurity to global popularity. (Note the coda on “Only from Exile Can We Come Home”: The Sugarhill Gang don’t feature directly in The Get Down’s storytelling, but they’re indirectly the beneficiaries of all the good we see done over the course of its unfolding mythmaking.) Now, with both halves of the season in the can, we get to appreciate and marvel at how well that gamble has paid off. Balancing this much plot isn’t easy, and if there are episodes that handle all that plot better than others, the fact that the show is able to balance it at all is impressive.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-