Space Matter: The Trouble with Spacesuits

Every aspect of space travel is difficult, but perhaps the hardest is the act of walking in space. When astronauts exit the International Space Station, they’re exposed to the vacuum of space. The only thing that’s protecting them is a pressurized suit, known as an EMU (Extravehicular Mobility Unit). And now, it appears as though we’re running out of them.

We’ve been using spacesuits since Mercury (the first American spacewalk occurred on Gemini 4), but the current spacesuit was designed and built for the Space Shuttle program. Of course they’ve been upgraded, modified, and refurbished since then, but the fact remains: These suits were originally designed to last fifteen years. Almost forty years later, they’re wearing out.

This is a huge problem, given the timeline for the International Space Station. Right now, the ISS is scheduled to be operated through the year 2024. It’s likely that will be extended through the year 2028. And according to NASA’s own investigations and a report from the NASA Office of the Inspector General, the current plan to maintain and support the station with the spacesuits we currently have will be a real challenge.

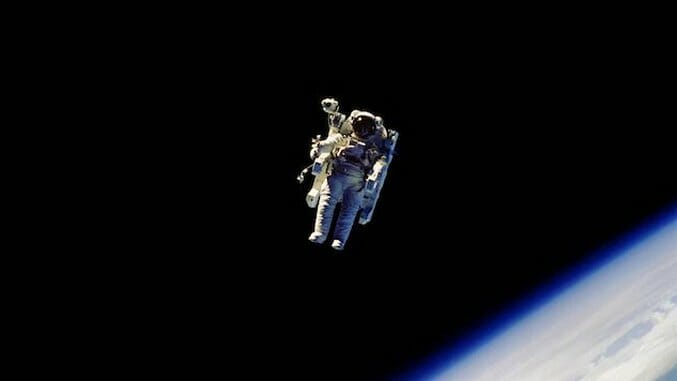

Astronaut David A. Wolf participates in a 2002 space walk (Image credit: NASA)

Astronaut David A. Wolf participates in a 2002 space walk (Image credit: NASA)

![]()

NASA’s current crop of spacesuits, or EMUs, have two different components: the Pressure Garment System, or PGS, and the Primary Life Support System, or PLSS. The PGS is responsible for maintaining pressure around the astronauts (as we need a minimum of 3 pounds per square inch of oxygen for our bodies to function), while the PLSS is basically a life-support backpack. It provides temperature control, oxygen, and scrubs carbon dioxide. The problem is, there are only 11 functional PLSSs left, out of an original 18.

When the Space Shuttle program was still running, issues with existing spacesuits were less of a problem. The EMUs could be regularly returned to Earth for inspection and maintenance. But now, SpaceX’s Dragon is the only vehicle that can both carry supplies to the ISS and return items to Earth. (The Russian Soyuz can as well, but the weight/cargo space on those is usually reserved for astronauts because it’s currently the only vehicle capable of ferrying humans to and from the ISS. And spacesuits are big.)

As a result, NASA has been pushing the limits on how long EMUs can go without maintenance. You’d think that the older the suits got, the more refurbishment they’d need to make sure they’re performing up to spec. The suits were originally authorized for a single Shuttle mission before maintenance. In 2000, that interval was extended to 1 year. That continued to increase until 2008, when the “ground maintenance interval [was] extended to 6 years, with in-flight maintenance and additional ground processing,” NASA OIG Analysis of EVA Office Information.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Astronaut Soichi Noguchi trains for a space walk in the Neutral Buoyancy Lab (Image credit:

Astronaut Soichi Noguchi trains for a space walk in the Neutral Buoyancy Lab (Image credit:  A prototype of the Exploration Development Suit (Image credit:

A prototype of the Exploration Development Suit (Image credit: