The 50 Best Serial Killer Movies of All Time

As recently as 2017, it was estimated by one nonprofit organization studying unsolved murders in the FBI database that there may be as many as 2,000 serial killers active in the United States at any given time.

Suffice it to say, they’re not all the stuff of classic horror movie plotting. Few are cannibals. Few live in rambling old mansions with secret passages and a private dungeon in the basement. Even fewer leave behind fiendishly complex cryptographs for a harried, chainsmoking detective and his partner to debate over plates of greasy diner eggs and black coffee. The more frightening reality is that many of them pass as the “average” people we interact with every day. That’s how these stories seem to go: A serial killer is not the sinister-looking stranger who just rolled into town; it’s that quiet next door neighbor who “kept to himself, mostly.” But that’s not what you see in serial killer movies.

Perhaps that’s why cinema has such a fascination with the more grandiose, manic version of the serial killer—these stories thrill us even as they’re distracting us from the more pressing danger and mundanity of everyday evil. Regardless, the concept of “a killer on the loose” has been rich cinematic soil for almost as long as film has existed. Go all the way back to 1920’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and what you basically have is a serial killer story—albeit, one in which the murders are being carried out by a hypnotized somnambulist. But the point stands.

Below, we’ve gathered the 50 greatest films about serial killers: a nightmare gallery of murderers both fantastical and disturbingly everyday. Granted, there are a lot of films about people getting killed serially—too many to take into consideration and compare without some basic parameters. So, here’s how we’re defining the idea of serial killer movies.

The killers in these films must be human. Vampires, werewolves and giant sharks all kill serially, but they’re not “serial killers” per se.

The killers can’t possess any overt supernatural powers or abilities. They can’t be ghosts, or undead revenants. This means, for example, that Michael Myers of Halloween is still able to qualify, as he is definitely a human being, whereas Jason Voorhees of Friday the 13th or Freddy Krueger of A Nightmare on Elm Street do not, given that one is (typically) an undead golem and the other is a supernatural dream monster.

Ultimately, these are all stories about genuine human beings, killing other human beings. Got it? There’s some obvious crossover with our list of the best slasher movies of all time, so be sure to check that out as well.

50. PiecesYear: 1982

Director: Juan Piquer Simón

Pieces is the sort of silly, head-scratching early ’80s slasher wherein it’s difficult to decide if the director is trying to slyly parody the genre or actually believes in what he’s doing. Regardless, Pieces is a delightfully stupid movie, featuring a killer who murders his mother with an axe as a child after she scolds him for assembling a naughty adult jigsaw puzzle. All grown up, he stalks women on a college campus and saws off “pieces” in order to build a real-life jigsaw woman. The film’s individual murder sequences are completely and utterly bonkers, the best one being a sequence in which the female lead is walking down a dark alley and is suddenly attacked by a tracksuit-wearing “kung fu professor” played by “Brucesploitation” actor Bruce Le. After she incapacitates him, he apologizes, saying he must have had “some bad chop suey,” and waltzes out of the movie. The whole thing takes less than a minute. Pieces also boasts one of the best film taglines of all time: “Pieces: It’s exactly what you think it is!” As schlock goes, it’s an unheralded classic. —Jim Vorel

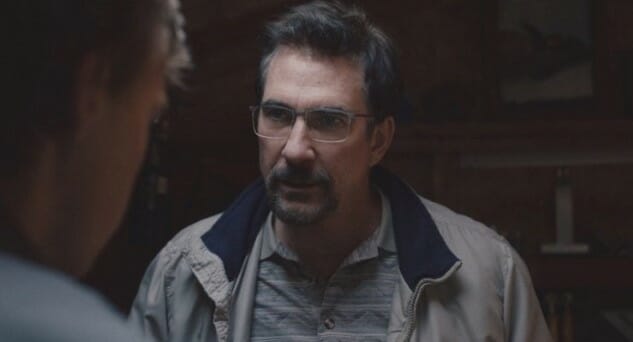

49. The Clovehitch KillerYear: 2018

Director: Duncan Skiles

Life in small-town Christian America can have a stultifying effect on a person, sucking out all personality and vitality, replacing all individual identity with better living through dogma. In The Clovehitch Killer, director Duncan Skiles replicates this bait-and-switch through cinematographer Luke McCoubrey’s camera. The film is shot stock-still, the camera more or less fixed from one scene to the next, as if affected by the vibe of routine humming throughout its setting of Somewhere, Kentucky. Almost none of the characters we meet in the movie have a spark; they’re drones tasked with maintaining the hive’s integrity against interlopers who, god forbid, actually bother to be somebody. Caught up in this dynamic is Tyler (Charlie Plummer), awkward, quiet and shy, the son of Don (Dylan McDermott), a handyman and Scout troop leader, which brings no end of unexpressed consternation to Tyler as a Scout himself. On the surface, Don looks and acts like an automaton, too, with occasional hints of humor and warmth in his capacity as father and Scoutmaster. Beneath, though, he’s something more, at least so Tyler suspects: The Clovehitch Killer, a serial killer who once tormented their area with a horrific murder spree long completed. Or maybe not. Maybe Don just has a real kink fetish and keeps rope around for fun in the bedroom. Either way, fathers aren’t always who or what they appear.

Horror movies are all about the squirm, the nerve-wracking build-up of tension over time that, done properly, leaves viewers crawling out of their skin with dread. In The Clovehitch Killer, this sensation is wrought entirely through craft instead of effects. That damn camera, motionless and unstirred, is always happy to film what’s in front of it, never one to pan about to catch new angles. What you see is what it shows you, but what it shows you might be more awful than you can stomach at a glance. This is a devilish movie that does beautifully what horror films are meant to—vex us with fear—through the most deceptively simple of means. —Andy Crump

48. The HitcherYear: 1986

Director: Robert Harmon

In horror films, there’s something alluring to a relentless and unstoppable killer whose motivation is only to destroy innocent life with nihilistic, almost supernatural fervor. Part of the reason the original Halloween is still so frightening lies in its chillingly effortless ability to present Michael Myers as a figure of death itself: no reason, no rhyme, he won’t stop until you stop breathing. The original The Hitcher operates on many of the same levels, as the simplicity of its premise about a couple (C. Thomas Howell and Jennifer Jason Leigh, who takes on a dual role, as the top and bottom halves of her body) hounded by a murderous maniac hitchhiker (Rutger Hauer) takes full advantage of the unresolved mystery surrounding the killer’s motivations. (Transform the truck from Duel into Rutger Hauer, and you get The Hitcher.) Director Robert Harmon’s film casts an appropriately icky, low-grade aura, perfectly fitting the killer’s philosophical point-of-view, an aesthetic approach that eludes the makers of the ill-fated 2007 remake, which looks too glossy to work on a visceral level. Also, with all due respect to Sean Bean, he’s no Rutger Hauer. —Oktay Ege Kozak

47. The Boy Behind the DoorYear: 2021

Director: David Charbonier, Justin Powell

The thing childhood abduction/serial killer story The Boy Behind the Door relies on the most is not nostalgia, though if you’re an adult, it may feel that way. The power of friendship is what keeps the heart of this film pumping fresh blood until the very end. There is something so sweet and unbreakable about a true childhood kinship, and that treasured bond is ripe between Bobby and Kevin. They are each other’s rock, and their dialogue and character impulses solidify this important piece of the puzzle that aids them throughout. Their mantra, “friends till the end,” sustains them through their trials and tribulations, and it is beyond clear that their symbiotic connection is their greatest asset. It’s easy, as a viewer, to feel deep catharsis with this element and your mind will wander back to those idyllic childhood moments with whomever was your best bud. But it seems the filmmakers also made it a point to take those feelings a step further: Their story makes you so thankful for those times, amid the uncertainty of life and the insidiousness of humanity, that the feeling will unsettle you. And, like The Boy Behind the Door, it should. —Lex Briscuso

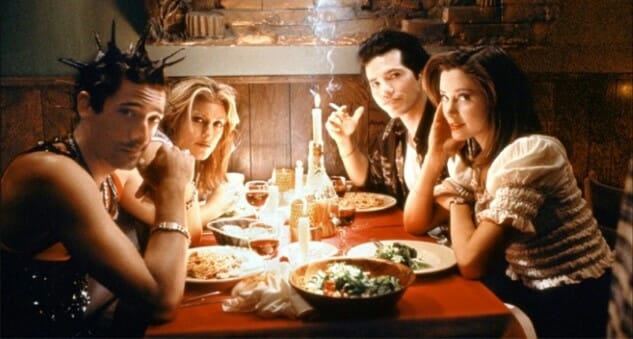

46. Summer of SamYear: 1999

Director: Spike Lee

Summer of Sam technically isn’t about the Son of Sam killer, who terrorized New York City during the summer of 1977 with his weapon of choice, a 44-caliber handgun— it’s a return for director Spike Lee to exploring how much irreversible damage unfounded paranoia and unchecked prejudice can inflict on neighborhoods, friendships and relationships. In a way, Summer of Sam operates as a mini-Do The Right Thing retread, focusing less overtly on race and more on how society marginalizes people who, for whatever reason, are different. When Richie (Adrian Brody) returns to his conservative Italian neighborhood dressing and acting like a proud member of a British punk band, the immediate reaction from his old friends is that he’s a freak, so he must be responsible for the murders that plague the city. Lee treating Son of Sam’s exploits as a sub-plot—Summer of Sam may feel a bit bloated and overlong, actually, with too many characters and sub-plots—actually works in heightening the visceral shock of the film’s killings: The death scenes lack the usual suspense of a standard serial killer flick, so that when the killer casually approaches his victims and empties his gun, the violence begins suddenly and ends suddenly, allowing us to contemplate the matter-of-factness of it, in direct contrast to more strangely macabre sequences, like when the killer has a conversation with a dog. —Oktay Ege Kozak

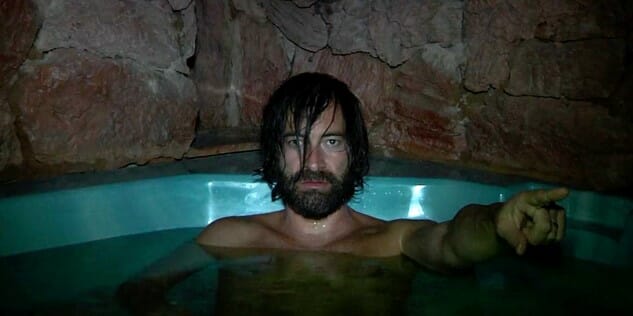

45. Creep 2Year: 2017

Director: Patrick Brice

Creep was not a movie begging for a sequel. About one of cinema’s more unique serial killers—a man who seemingly needs to form close personal bonds with his quarry before dispatching them as testaments to his “art”—the 2014 original was self-sufficient enough. But Creep 2 is that rare follow-up wherein the goal seems to be not “let’s do it again,” but “let’s go deeper”—and by deeper, we mean much deeper, as this film plumbs the psyche of the central psychopath (who now goes by) Aaron (Mark Duplass) in ways both wholly unexpected and shockingly sincere, as we witness (and somehow sympathize with) a killer who has lost his passion for murder, and thus his zest for life. In truth, the film almost forgoes the idea of being a “horror movie,” remaining one only because we know of the atrocities Aaron has committed in the past, meanwhile becoming much more of an interpersonal drama about two people exploring the boundaries of trust and vulnerability. Desiree Akhavan is stunning as Sara, the film’s only other principal lead, creating a character who is able to connect in a humanistic way with Aaron unlike anything a fan of the first film might think possible. Two performers bare it all, both literally and figuratively: Creep 2 is one of the most surprising, emotionally resonant horror films in recent memory. —Jim Vorel

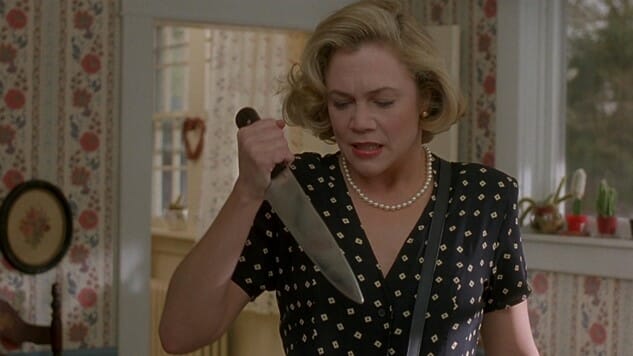

44. Serial MomYear: 1994

Director: John Waters

Ever the prescient scumbag sophisticate, John Waters presaged America’s true crime fixation—in the wake of the Menendez brothers and the Pamela Smart trials, before, even, Gus Van Sant’s groundbreaking To Die For, and in the glow of the OJ Simpson murders—with the tongue-through-cheek Serial Mom. Farce at the fore, Waters fully understands the power of having Kathleen Turner play the titular murderer, a woman whose attractiveness, domesticity and class status allow her the unearned sympathy and forgiveness her despicable crimes require in order to continue, but never shies away from juxtaposing the friendliness of Beverly Sutphin’s (Turner) demeanor with the putrid nature of her psyche, producing a film as upsetting as it is hilarious about the corrupt core of society’s cravings for such shitty stuff. Even as her family attempts to curb her homicidal ways, Beverly succeeds in ending the lives of those whose lives she wants to end, her husband (Sam Waterston) and daughter (Ricki Lake) and son (Matthew Lillard) helpless against the tide of ratings and Nielsen numbers working to thwart them. With little room for debate, Waters lays the blame for such blithe misery at our feet, insisting that with every bit of reality TV wretchedness we consume, we encourage another psychopath to take that extra step toward their own 15 minutes of sinister stardom. —Dom Sinacola

43. Black WidowYear: 1987

Director: Bob Rafelson

Taking the femme fatale conceit to literal extremes, director Bob Rafelson, whose credits include Five Easy Pieces and the 1981 remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice, delivers a modern noir elevated by two ace lead performances. Debra Winger does Debra Winger as an FBI agent, Alex, who grows obsessed with the perpetrator of a series of unsolved marriages-then-murders. Theresa Russell matches her note for note as gold-digging vixen Catharine, who’s as good at the long con as she is a cat-and-mouse game with Winger’s humdrum suit. Then there’s the staggering amount of research involved—Catharine on the passions of her soon-to-be victims, Alex on her suspect. It’s smart, with pointed gender commentary to boot. The plain-Jane Fed plays frenemies with the glamorous chameleon while cinematography great Conrad L. Hall (Cool Hand Luke, American Beauty) mines suspense in the shadows, all the better to spotlight Russell’s steely eyes and porcelain veneer—she’s bone-chilling. Bonus points for a droll cameo from Dennis Hopper as one of Catharine’s marks, and a lecherously long-nailed Diane Ladd as one of his relatives. —Amanda Schurr

42. Death ProofYear: 2007

Director: Quentin Tarantino

Kurt Russell plays serial killer Stuntman Mike in Death Proof, Quentin Tarantino’s half of the double-feature Grindhouse, but the cars are the real stars. Just as he does in all of his works, Tarantino fills the lives of his diverse menagerie of characters with his trademark blend of mundane pop-cultural dialogue and insane violence. In one exhilarating sequence, real-life stuntwoman Zoe Bell precariously hangs onto the hood of a speeding car in what is one of the greatest chase scenes in cinematic history. Ultimately, Death Proof will never be considered one of Tarantino’s “major works”—especially after the recent revelations of Uma Thurman’s car accident on the set of Kill Bill—but it’s still a satisfying shot of righteous adrenaline to see Stuntman Mike finally get what’s coming to him. —Tim Basham

41. Deranged: Confessions of a NecrophileYear: 1974

Directors: Alan Ormsby, Jeff Gillen

Imagining Deranged as the loose prequel to Home Alone makes Buzz’s tall tales about the creepy next-door-neighbor the stuff of actual nightmares. In Alan Ormsby and Jeff Gillen’s nasty-ass Canadian cult curio, Roberts Blossom plays Ezra Cobb (his only starring role, though it never gained close to the amount of attention he garnered as misunderstood Old Man Marley), a deeply unsettling small-town weirdo who harbors a disturbing obsession with his recently-deceased mother, which of course grows into a murderous spree to gather more corpses to keep his mother’s corpse company. Like most stories about serial killers, Ezra’s mental afflictions draw liberally from pop culture’s morbid fascination with the—cough—deranged individuals who exist in every domesticated corner of the planet, disguising their neuroses to function within society, and so Deranged pulls from the story of Ed Gein as much as it seems to pull from the shocking realism of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre—which came out the same year (the two films probably pulling from the same collective pool of unconscious Jungian fears)—reveling in breaking one taboo after another, unfazed by the gruesomeness portrayed on screen. Deranged does get gross, its final moments revealing that, like so many films of its ilk, this could only happen in a godless universe, a universe in which there is no reason or purpose to evil. Throughout it all, Blossom delivers a stomach-churning performance, his face a graveyard of shadows and terrible memories pushed to Jim-Carrey-like levels of elasticity, as inhuman as it is strictly corporeal. In retrospect, one understands Buzz’s warnings, however manipulative they may’ve been: Blossom’s is the face of a guy who could beat an innocent bystander to death with a snow shovel without flinching. —Dom Sinacola

40. I Am Not a Serial KillerYear: 2016

Director: Billy O’Brien

On the surface, this overlooked 2016 gem feels subtly familiar to those who have perhaps seen series such as Dexter: a boy (Max Records) with pronounced sociopathic tendencies fears he is “fated” to become a serial killer, and thus lives by a set of rules designed to keep those around him safe. But the film makes the unusual distinction of having young John Wayne Cleaver’s mental and emotional condition be much better understood by those around him than is typical for films in this genre—they’re at least attempting to be allies, whether he can see it or not. Records is captivating as the lead, projecting a fascination with the icky inner workings of both the human body and human condition, while a 78-year-old Christopher Lloyd steals the show as John’s doddering but dangerous next-door-neighbor. Low-budget but gory and stylish in spades, I Am Not a Serial Killer is a film whose final act diverges from the expected narrative in ways that may be shocking, to say the least, but throughout it maintains a rock-solid grasp on its fundamental themes of emotion, family and predestination. —Jim Vorel

39. ManiacYear: 2012

Director: Franck Khalfoun

Maniac is a rather impressive reimagining of the 1980 exploitation horror film of the same name, an attempt to take some grindhouse material and redress it in a modern skin, equal parts shocking and thought-provoking. Elijah Wood gives a transformative performance as the killer, Frank Zito, even though you almost never see Wood’s face, given that the entire movie is filmed from the killer’s perspective—yes, the entire film. Rather, the audience hears the running background noise of his madness as he mutters to himself and stalks his female victims. Be warned: The violence of Maniac is difficult to watch for even seasoned horror vets, and the constant POV shot of the killer’s perspective immediately makes the audience feel both guilt at their complicity and sick at their solidarity with the killer. Some will call it overly gratuitous in terms of its brutality, but the film is so assured in its artistic aims that it’s difficult to hold to the criticism. Set to a score of alternating, Carpenter-esque synth and classical/opera music, Maniac is an arthouse gore film if there ever was one. —Jim Vorel

38. CruisingYear: 1980

Director: William Friedkin

A source of uproar and protest upon its original release, William Friedkin’s Cruising saw the director dip his toes again into gay subculture, and though he moved from the middle class, booze-soaked apartments of The Boys in the Band (1970) to underground, sweat-stained leather bars, little changed in terms of how he conceptualized how gay men conceptualized their own fears and desires. Outsider perspective or not, the link between his adaptation of Mart Crowley’s Albee-esque play and Gerald Walker’s pulpy noir of a thriller is self-loathing, both about adult men whose entire identities are contingent on how well they can numb themselves. Friedkin’s Cruising frames that anxiety within the story of a cop, Steve Burns (Al Pacino), who goes undercover in New York’s leather culture to find a serial killer murdering men on the scene, Friedken’s connection between sex and death amplified because of its queerness. If the director has a gawky, wandering eye, it seems logical that Pacino’s Burns, too, is entranced, repulsed, attracted to and captivated by a manifestation of maleness that deliberately mixes the foreign and familiar. Like an amalgamation of the danger of toxic masculinity and a prophetic meditation on the AIDS crisis (the first report of AIDS was not published in the New York Times until July 3, 1981), Cruising is stunning as one man’s reluctant trip down a gay rabbit (glory) hole. —Kyle Turner

37. XYear: 2022

Director: Ti West

X is a remarkable and unexpected return to form for director Ti West, a decade removed from an earlier life as an “up and coming,” would-be horror auteur who has primarily worked as a mercenary TV director for the last 10 years. To return in such a splashy, way, via an A24 reenvisioning of the classic slasher film, intended as the first film of a new trilogy or even more, is about the most impressive resurrection we’ve seen in the horror genre in recent memory. X is a scintillating combination of the comfortably familiar and the grossly exotic, instantly recognizable in structure but deeper in theme, richness and satisfaction than almost all of its peers. How many attempts at throwback slasher stylings have we seen in the last five years? The answer would be “countless,” but few scratch the surface of the tension, suspense or even pathos that X crams into any one of a dozen or more scenes. It’s a film that unexpectedly makes us yearn alongside its characters, exposes us (graphically) to their vulnerabilities, and even establishes deeply sympathetic “villains,” for reasons that steadily become clear as we realize this is just the first chapter of a broader story of horror films offering a wry commentary on how society is shaped by cinema. Featuring engrossing cinematography, excellent sound design and characters deeper than the broad archetypes they initially register as to an inured horror audience, X offers a modern meditation on the bloody savagery of Mario Bava or Lucio Fulci, making old hits feel fresh, timely and gross once again. In 2022, this film is quite a gift to the concept of slasher cinema. —Jim Vorel

36. The CellYear: 2000

Director: Tarsem Singh

The career of director Tarsem Singh has never quite managed to live up to the promise first seen in 2000’s The Cell. This futurist, fantasist spin on The Silence of the Lambs sees a psychologist (Jennifer Lopez, back when she was an actor first and foremost) descending into the twisted mind of a serial killer (an unrecognizable Vincent D’Onofrio) via an experimental piece of technology that allows one person’s consciousness to be inserted into the subconscious of another. Presaging the likes of Inception, The Cell is startlingly imaginative at times, a visual feast that recalls Clive Barker’s fixations upon grandiosity and sadomasochism, as Lopez comes up against the killer’s mental projection, who dresses and behaves as an omnipotent god-king in a twisted dream world like something out of H.P. Lovecraft. Unpolished and self-congratulatory at times, one still has to admire its sheer chutzpah. If any of these films were going to be remade as an episode of Black Mirror in 2018, it would probably be this one. —Jim Vorel

35. TenebraeYear: 1982

Director: Dario Argento

If you wrote an ultra-violet horror book, and if your ultra-violent horror book inspired a workaday psycho to go on their own ultra-violent killing spree, would you be put off or would you take it as a compliment? Maybe that’s not the question Dario Argento asks in his notorious 1982 giallo film Tenebrae, but the plot does call to mind a certain old proverb about imitation and flattery: American author Peter Neal (Anthony Franciosa) heads to Italy to promote his new book, and finds that there’s a serial killer on the loose, emboldened by Neal’s bibliography and murdering Romans in his name. That’s gotta feel pretty good for Neal, though not so much for the killer’s victims. The guy isn’t exactly into efficiency; he prefers to make his prey suffer, which shouldn’t come as a surprise given Tenebrae’s source. (Argento isn’t into efficiency, either. He’ll kill people with random stockpiles of razor wire if he feels like it.)

Tenebrae, more so than other Argento movies, is tough to watch; it’s an especially bloody affair, but its artistic merit demands we consider it essential cinema. The film stages arterial geysers to soak its sets in crimson equally as often as it admits Argento’s own twisted indulgences as a filmmaker. He opens the film with a narration about finding freedom in taking life, for Christ’s sake. You figure it out. It’s not that Argento condones murder or anything as nutty as that; it’s more that he’s willing to confess his hopeless fixation with depicting murder on screen. When you’re possessed of as great a gift for that kind of thing as Argento, what reasonable person can blame you? —Andy Crump

34. FrenzyYear: 1972

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Hitchcock’s penultimate (and arguably last great) film is also his grisliest. As movie censors became slightly more relaxed in the 1970s, Hitchcock was allowed to show more violence and even some nudity. It’s still tame by today’s standards, but the tale of a London serial killer who rapes and strangles his female victims with a necktie is the master of suspense at his most graphic, while retaining the typically twisty, turny plotting you’d expect. —Bonnie Stiernberg

33. Black ChristmasYear: 1974

Director: Bob Clark

Fun fact—nine years before he directed holiday classic A Christmas Story, Bob Clark created the first true, unassailable “slasher movie” in Black Christmas. Yes, the same person who gave TBS its annual Christmas Eve marathon fodder was also responsible for the first major cinematic application of the phrase “The calls are coming from inside the house!” Black Christmas, which was insipidly remade in 2006, predates John Carpenter’s Halloween by four years and features many of the same elements, especially visually. Like Halloween, it lingers heavily on POV shots from the killer’s eyes as he prowls through a dimly lit sorority house and spies on his future victims. As the mentally deranged killer calls the house and engages in obscene phone calls with the female residents, one can’t help but also be reminded of the scene in Carpenter’s film where Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) calls her friend Lynda, only to hear her strangled with the telephone cord. Black Christmas is also instrumental, and practically archetypal, in solidifying the slasher trope of the so-called “final girl.” Jessica Bradford (Olivia Hussey) is actually among the better-realized of these final girls in the history of the genre, a remarkably strong and resourceful young woman who can take care of herself in both her relationships and deadly scenarios. It’s questionable how many subsequent slashers have been able to create protagonists who are such a believable combination of capable and realistic. —Jim Vorel

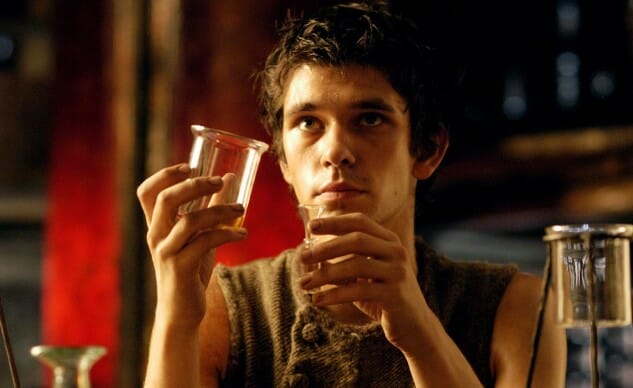

32. Perfume: The Story of a MurdererYear: 2006

Director: Tom Tykwer

An orphan with a superhuman sense of smell makes the startling discovery that he has no scent of his own, and his quest for the ultimate perfume takes a very dark turn. Adapted from Patrick Susskind’s novel Perfume and set in 18th century France, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer stars Ben Whishaw as Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, an unfortunate urchin who’s sold to a tanner but finds his way into becoming a perfumer’s apprentice. The perfumer (Dustin Hoffman) ultimately sends him to the perfume masters of Grasse, France, to learn enfleurage, the art of extracting essences by coating them with fat. Jean-Baptiste isn’t interested in jasmine and lavender, though. He wants to distill and reproduce the essence of people, particularly beautiful virgins. So naturally he goes on a rampage of murders to capture some personal scents. Ultimately he’s caught and slated for a very grisly execution, but he’s stashed away the perfume he’s concocted from the women he’s killed, and covers himself with it, causing everyone to declare he is innocent, and possibly an angel, provoking a frenzy in which the townspeople devour him.

Directed by Tom Tykwer, the film received mixed responses from critics, with the general consensus that its excellent cinematography was undermined by a less-than-stellar script. (Even Alan Rickman, as the wealthy Antoine Richis, father of the final victim, couldn’t sound 100% convincing at times.) Fans of the novel might find the film’s deviations annoying, and it is profoundly challenging to successfully evoke the sense of smell on film. However, any connoisseur of serial killer movies should have this one under their belt if purely for the unusual, and slightly magical, high concept. Beneath the uneven writing there’s some pretty deep philosophical questioning of the nature of human “essence,” or soul, and what it would be like to be without one. —Amy Glynn

31. ManhunterYear: 1986

Director: Michael Mann

Received at the time to mixed reviews, its hyper-aestheticized allure surprisingly a bit too much for audience tastes in the mid-’80s, Manhunter more than 30 years later represents (maybe ironically) what the mid-’80s felt like to those who can’t quite remember it concretely. In other words, it’s a movie unstuck in time, a product of a decade that’s long past but so surreal and steeped in symbolism and superbly manicured that it seems to hide generations of terror inside it. The first of many adaptations of Thomas Harris’s novels, Manhunter crafted the model and set the dead-serious stakes for every iteration to follow, mooring dream-like imagery to a careful police procedural, attempting to depict the harrowing emotional experience of being an FBI profiler while never skimping on the melodrama.

All the while, Mann draws big abstruse lines around the serial killer at the core of the film—a laconic lurch of a man, Francis Dollarhyde (Tom Noonan), the so-called “Tooth Fairy”—who inhabits every scene with the foreboding promise that he is a person whose reality is a fragile delusion. Brian Cox haunts the fringes of the film, the first actor to inhabit Hannibal Lecktor (for some reason, first spelled that way), the manifestation of Agent Will Graham’s (William Peterson) Id, a foil to the “good guy” and a psychopath whose lack of empathy makes all the starker Mann’s intuitive sense of framing. Abetted by DP Dante Spinotti’s willingness to treat color like he’s lighting a giallo as much as a Miami Vice-minded crime thriller, in Manhunter Mann found an early career balance between the gritty minutiae of investigative police work and the abstract, cerebral violence of the investigations themselves. Dollarhyde wants only to be wanted, so he kills to be truly “seen” by his victims, which then, in his mind, transforms him into something powerful. Manhunter acts in much the same way, growing stronger the harder you stare into it. —Dom Sinacola

30. CreepYear: 2014

Director: Patrick Brice

Creep is a somewhat predictable but cheerfully demented indie horror film, the directorial debut by Patrick Brice, who also released 2015’s The Overnight. Starring the ever-prolific Mark Duplass, it’s a character study of two men: naive videographer (played by Brice) and not-so-secretly psychotic recluse (Duplass), the latter hiring the former to come document his life out in a cabin in the woods. The found footage two-hander leans entirely on its performances, which are excellent, early back-and-forths between the pair crackling with a sort of awkward intensity. Duplass, who can be charming and kooky in something like Safety Not Guaranteed, shines here as the deranged lunatic who forces himself into the protagonist’s life and haunts his every waking moment. Anyone genre-savvy will no doubt see where it’s going, but it’s still a well-crafted ride that succeeds on the strength of the chemistry between its two principal leads in a way that reminds me of the scenes between Domhnall Gleeson and Oscar Isaac in Ex Machina. —Jim Vorel

29. Blood and Black LaceYear: 1964

Director: Mario Bava

You can credit films such as Psycho or Peeping Tom for laying the groundwork for the slasher genre, and 1974’s Black Christmas for first bringing all the elements together into what is undeniably a “slasher movie,” but Mario Bava’s foundational 1964 giallo is so close as to almost merit that title as the first “true” slasher in almost every way that matters. Blood and Black Lace is an absolutely gorgeous, sumptuous movie that is all the better to see on the big screen, if you can, featuring dramatic splashes of primary colors used to maximum impact. The story is a blend of darkly comic murder mystery and titillation-tinged exploitation, featuring a gaggle of female models stalked by a mysterious assailant whose face is covered in an impenetrable stocking mask with blank features—a killer who looks for all intents and purposes like the DC Comics character The Question. It’s an immediately iconic image that seared its imprint into an entire Italian genre, and subsequent killers would reflect so many of this film’s killer’s features, from the black gloves and long coat to the mask itself. Although many tried to ape its visuals, very few could match the decadence and the sense of luxurious (and deadly) excess that Bava captures in Blood and Black Lace. —Jim Vorel

28. The Element of CrimeYear: 1984

Director: Lars Von Trier

While Lars von Trier trained at Copenhagen’s premier film school, his twisted little mind made its auspicious debut with The Element of Crime in 1984. Even before Dogme 95, in which he made a bunch of rules only to ruefully break them, von Trier’s preoccupations were on the subversive from the get go. This neo-noir exploration on guilt and obsession set the groundwork for films like Europa, with its tricky somnambulatory tone, and even films as far forward as Nymphomaniac, in which he returned to testing the limits of desire and destruction between men and women. In The Element of Crime, his post-apocalyptic vision of Europe (part of his “Disintegration of Europe” trilogy), a former cop/current ex-pat detective, Fisher (Michael Elphick), recalls his last case, concerning a serial killer who strangled, raped and mutilated young girls. As influenced by Blade Runner as he is by Kafka, von Trier spins a classic tale of spiritual annihilation by way of imitation: Fisher uses a book called The Element of Crime to identify with the killer and, therefore, begins to see himself meld with the elusive culprit. Von Trier was button-pushing right out of the gate, his palette urine-painted and garish, and his obsessions provocative. With his first feature, the Danish director knowingly established himself as an incomparable enfant terrible. —Kyle Turner

27. The Bad SeedYear: 1956

Director: Mervyn LeRoy

The Bad Seed is one of the most disturbing American portraits of pure psychopathy or sociopathy, coming from the least suspected of all sources: an 8-year-old girl. The piercing eyes of little blonde, pigtailed Rhoda (Patty McCormack) are terrifying to behold, moreso once we begin to suspect what lays behind her facade. Rhoda’s ability to function and hide her true self with wily cunning foretells the likes of Patrick Bateman or Henry in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, but the seeming ease with which she does so is especially disturbing. There could be no We Need to Talk About Kevin without The Bad Seed there to ask the question: What is the nature of innate evil? The menace and sheer, unflinching look into human cruelty in The Bad Seed is truly unique for its time period, with young McCormack’s performance ranking among the all-time greats for children in a horror film. The Bad Seed is about the horrors of responsibility as a parent, when there’s something you know needs to be done but the act of carrying it out is something the world will never be able to understand. It’s a film that may turn you off pigtails for life. —Jim Vorel

26. Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie VernonYear: 2006

Director: Scott Glosserman

In the years following Scream, there was no shortage of films attempting similar deconstructions of the horror genre, but few deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as the criminally underseen Behind the Mask. Taking place in a world where supernatural killers such as Jason Voorhees and Freddy Krueger actually existed, this mockumentary follows around a guy named Leslie Vernon (Nathan Baesel), who dreams of being the “next great psycho killer.” In doing so, it provides answers and insight into dozens of horror movie tropes and clichés, like: How does the killer train? How does he pick his victims? How can he seemingly be in two places at once? It’s a brilliant, twisted love letter to the genre that also develops an unexpected stylistic change right when you think you know where things are headed. And, despite a lack of star power, Behind the Mask boasts tons of cameos from horror luminaries: Robert Englund, Kane Hodder, Zelda Rubinstein and even The Walking Dead’s Scott Wilson. Every, and I mean every, horror fan needs to see Behind the Mask. It’s criminal that Glosserman has never managed to put together a proper sequel follow-up, but a fan-funded comic series raised twice its goal on IndieGoGo, so maybe it’s still possible. —Jim Vorel

25. Man Bites DogYear: 1992

Directors: Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel, Benoît Poelvoorde

An undeniable forebear to Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon, Man Bites Dog won the International Critics’ Prize at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival, only to receive an NC-17 rating upon its US release, banned in Sweden altogether. One can understand the squeamishness: Man Bites Dog unflinchingly portrays serial murder in its graphic banality, victims ranging from children to the elderly to a gang-raped woman whose corpse is later photographed with her entrails spilling all over the table on which she was violated, the perpetrators lying in drunken post-revelry, heaped on the floor. Filmed as a mockumentary, Man Bites Dog goes to distressing lengths to portray the exigencies of murder as basely as possible, incorporating the reluctance of the crew filming such horrors to offer the audience a reflection of the ways they were probably reacting. The fascinated sorrow expressed by the documentary film’s director (Rémy Belvaux) as he realizes what making a documentary film about a serial killer actually means, becoming more and more complicit with the killings as the film goes on, explicitly points to our willingness as bystanders to stomach the horrors displayed. Still, we react viscerally while the film explores conceptual themes of true crime as pop culture commodity and reality TV as detrimental mitigation of truth, ultimately indicting viewers apt to enjoy this movie while simultaneously catering to them. Benoit (Benoît Poelvoorde), the subject of the faux film, is of course an incredibly intelligent societal outcast beset by xenophobia and misogyny, offering up countless neuroses to explore behind his psychopathy and serial murder, which he treats as a legitimate job. But Man Bites Dog is more about the ways in which we consume a movie like Man Bites Dog, concerned less about the flagrant killing it indulges for laughs than it is the laughs themselves, implying that the real blame for such well-known horror falls at our feet, in which each day we take big, basic steps to normalize the violence and hate that constantly surrounds us. —Dom Sinacola

24. Deep RedYear: 1975

Director: Dario Argento

Dario Argento’s movies would be easy to pick out of a police lineup, because when you add all of his little quirks together they form an instantly iconic style. Deep Red is one of those films that simply couldn’t have been made by anyone else—Mario Bava could have tried, but his wouldn’t have the quintessential soundtrack by Argento collaborators Goblin, nor the drifting, eccentric camerawork that constantly makes us question whether we’re looking through the killer’s POV or not. And the story is a classic giallo whodunit: Following the brutal cleaving of a German psychic (Macha Méril), a music teacher (David Hemmings) who lives in her building starts putting the pieces together to solve the murder mystery, uncovering a tragic family history. Along the way, anyone who gets close to the answer gets a meat cleaver to the head from a mysterious assailant in black leather gloves—except for those who die in much worse, more gruesome ways. Argento has a real eye for what is physically disconcerting to watch—he somehow takes scenes that are “standard” for the horror genre and makes them much more uncomfortable than one would think by simply reading a description of the sequence. In Argento’s hands, a slashing knife becomes a paintbrush. —Jim Vorel

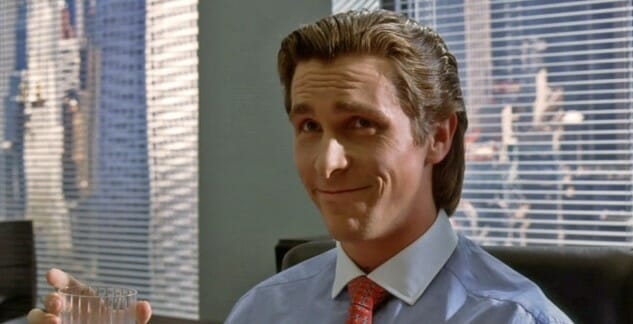

23. American PsychoYear: 2000

Director: Mary Harron

There’s something wrong with Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale)—really wrong. Although he writhes within a Christopher Nolan-esque what-is-a-dream conundrum, Bateman is just all-around evil, blatantly expressing just how insane he is, unfortunately to uncaring or uncomprehending ears, because the world he lives in is just as wrong, if not moreso. Plus the drug-addled banker has a tendency to get creative with his kill weapons. (Nail gun, anyone?) Like anybody needed another reason to hate rich, white-collar Manhattanites: Mar Harron’s adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ is a scintillating portrait of corporate soullessness and disdainful affluence. —Darren Orf

22. FrailtyYear: 2001

Director: Bill Paxton

Frailty is scary in much the same way that Jeff Nichols’ Take Shelter is so unsettling: They’re both about fathers who become possessed by the idea that they have a mission in life, a secret commandment from on high that may or may not be due to the slow onset of mental illness. The late Bill Paxton wrote and starred in this passion project, giving himself one of the best roles of his career as that disintegrating father who has come to believe that he’s living in a world surrounded by “demons” God has ordered him to eradicate. From the point of view of his young protagonist sons, they’re trapped in a situation that is both hopeless and terrifying, between their father, an alien, unknowable personality ordering them to assist him in committing atrocities, and the fact that revealing his apparent madness to the world will likely mean losing him forever. Matthew McConaughey is supplied with an unexpectedly juicy, unheralded role as one of the grown-up brothers who has come to terms with his nasty childhood, but Paxton really steals the show with the kind of nervous energy that makes it impossible to tell what he’ll do next. Also: Prepare yourself for one zany ending. —Jim Vorel

21. Eyes Without a FaceYear: 1960

Director: Georges Franju

I remember seeing my first Édith Scob performance back in 2012, when Leos Carax’s Holy Motors made its way to U.S. shores and melted my pea brain. I also remember Scob donning a seafoam mask, every bit as blank and lacking in expression as Michael Myers’, in the film’s ending, and thinking to myself, “Gee, that’d play like gangbusters in a horror movie.”

What an idiot I was: At the time of my Holy Motors viewing, Scob had already appeared in that horror movie, Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face, an icy, poetic and yet lovingly made film about a woman and her mad scientist/serial killer dad who just wants to kidnap young ladies that share her facial features in hopes of grafting their skin onto her own disfigured mug. (That’s father of the year material right there.) Of course, nothing goes smoothly in the film’s narrative, and the whole thing ends in tears plus a frenzy of canine bloodlust. Eyes Without a Face is played in just the right register of unnerving, perverse and intimate as the most enduring pulpy horror tales tend to be. If Franju gets to claim most of the credit for that, at least save a portion for Scob, whose eyes are the single best special effect in the film’s repertoire. Hers is a performance that stems right from the soul. —Andy Crump

20. Henry: Portrait of a Serial KillerYear: 1986

Director: John McNaughton

Henry stars Merle himself, Michael Rooker, in a film which is essentially meant to approximate the life of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, along with his demented sidekick Otis Toole (Tom Towles). The film was shot and set in Chicago on a budget of only $100,000, and is a depraved journey into the depths of the darkness capable of infecting the human soul. That probably sounds like hyperbole, but Henry really is an ugly film—you feel dirty just watching it, from the filth-crusted urban streets to the supremely unlikeable characters who prey on local prostitutes. It’s not an easy watch, but if gritty true crime is your thing, it’s a must-see. Some of the sequences, such as the “home video” shot by Henry and Otis as they torture an entire family, gave the film a notorious reputation, even among horror fans, as an unrelenting look into the nature of disturbingly mundane evil. —Jim Vorel

19. ScreamYear: 1996

Director: Wes Craven

Before Scary Movie or A Haunted House were even ill-conceived ideas, Wes Craven was crafting some of the best horror satire around. Although part of Scream’s charm was its sly, fair jabs at the genre, that didn’t keep the director from dreaming up some of the most brutal knife-on-human scenes in the ’90s. With the birth of the “Ghost Face” killer, Craven took audiences on a journey through horror-flick fandom, making all-too-common tricks of the trade a staple for survival: sex equals death, don’t drink or do drugs, never say “I’ll be right back.” With a crossover cast of Neve Campbell, Courteney Cox, David Arquette, Matthew Lillard, Rose McGowan and Drew Barrymore (OK, she’s only in the opening, but still), Scream arrived with an incisive take on a tired batch of movies. It wasn’t the first of its kind, but it was the first to be embraced by a huge audience, which went a long way in raising the genre IQ of the burgeoning horror fan. —Tyler Kane

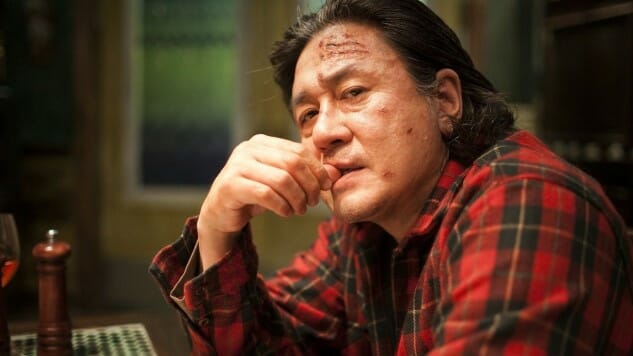

18. I Saw the DevilYear: 2010

Director: Kim Jee-woon

I Saw the Devil is a South Korean masterpiece of brutality by director Kim Ji-woon, who was also behind South Korea’s biggest horror film, A Tale of Two Sisters. It’s a truly shocking film, following a man out for revenge at any cost after the murder of his wife by a psychopath. We follow as the “protagonist” of the film makes sport of hunting said psychopath, embedding a tracker in the killer that allows him to repeatedly appear, beat him unconscious and then release him again for further torture. It’s a film about the nature of revenge and obsession, and whether there’s truly any value in repaying a terrible wrong. If you’re still on the fence, know that Choi Min-sik, the star of Park Chan-Wook’s original Oldboy, stars as the serial killer being hunted and turns in another stellar performance. This is not a traditional “horror film,” but it’s among the most horrific on the list in both imagery and emotional impact. —Jim Vorel

17. Memories of MurderYear: 2003

Director: Bong Joon-Ho

Based on the case of South Korea’s first serial killer, this is Bong Joon-Ho’s take on the cop drama. The tension arises from the clash in styles between a detective from the countryside (Song Kang-Ho), and his urban counterpart (Kim Sang-Kyung) dispatched to speed the investigation, which steadily derails amid blown opportunities and wrongful arrests. One uses his fists, the other forensics, and both serve as cultural archetypes whose actions play out against the backdrop of the mid-1980s military dictatorship. Strange as it sounds, Murder is also not without laughs, which are both coarse and piercing. —Steve Dollar

16. The VanishingYear: 1988

Director: George Sluizer

Ever wondered what makes a mastermind like Stanley Kubrick shake in his boots? The answer is The Vanishing, which was apparently the most “terrifying” film he’d ever seen (and this, coming from the guy who made The Shining). In fact, what makes this thriller so unnerving is that it’s told all topsy-turvy: Instead of spending two hours trying to figure out the identity of the bad guy, we’re introduced to him right away. Based on Tim Krabbé’s book The Golden Egg (Het Gouden Ei), the film tells the story of Raymond (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu), a self-diagnosed sociopath trying to put himself through the ultimate test. Having saved a young girl from drowning, and celebrated as a hero by his daughters, he wants to find out whether his act of kindness can be followed up by a similarly impressive act of evil. As the film allows Raymond to, over time, investigate the line between sociopathy and psychopathy, he spends hours meticulously planning how to best go about abducting a woman, rather than rescuing one. He experiments with chloroform, purchases an isolated house and practices different ways of getting unknowing women to get into his car. Sluizer later remade his own film for American audiences, with Jeff Bridges and Kiefer Sutherland, but its ending was drastically changed. —Roxanne Sancto

15. OperaYear: 1987

Director: Dario Argento

Giallo is not the kind of genre in which directors end up receiving a lot of critical aplomb…with the occasional exception of Dario Argento. He is to the bloody, Italian precursor to slasher films as, say, someone like Clive Barker is to English-language horrors: an auteur willing to take chances, whose gaudy works are occasionally brilliant but just as often fall flat. Opera, though, is one of Argento’s most purely watchable films, about a young actress who seems to have developed a rather homicidal admirer, because anyone who gets in the way of her career has a funny way of ending up dead. Meanwhile, her constant nightmares hint at a long-buried connection to the killer. Essentially the giallo equivalent of Phantom of the Opera, Opera’s canvas is splashed by Argento’s signature color palette of bright, lurid tones and over-the-top deaths, laced with interesting subtext about the nature of watching horror films, as the heroine is often forced by the killer to witness the crimes unfold. Like even Argento’s worst, Opera is a master class study in craftsmanship. —Jim Vorel

14. HalloweenYear: 1978

Director: John Carpenter

For students of John Carpenter’s filmography, it is interesting to note that Halloween is actually a significantly less ambitious film than his previous Assault on Precinct 13 on almost every measurable level. It doesn’t have the sizable cast of extras, or the extensive FX and stunt work. It’s not filled with action sequences. But what it does give us is the first full distillation of the American slasher film, and a heaping helping of atmosphere. Carpenter built off earlier proto-slashers such as Bob Clark’s Black Christmas in penning the legend of Michael Myers, an unstoppable phantom who returns to his hometown on Halloween night to stalk high school girls (the original title was actually The Babysitter Murders, if you haven’t heard that particular bit of trivia before). Carpenter heavily employs tools that would become synonymous with slashers, such as the killer’s POV perspective, making Myers into something of a voyeur (he’s just called “The Shape” in the credits) who lurks silently in the darkness with inhuman patience before finally making his move. It’s a lean, mean movie with some absurd characterization in its first half (particularly from the ditzy P.J. Soles, who can’t stop saying “totally”) that then morphs into a claustrophobic crescendo of tension as Jamie Lee Curtis’ Laurie Strode first comes into contact with Myers. Utterly indispensable to the whole thing is the great Donald Pleasance as Dr. Loomis, the killer’s personal hype man/Ahab, whose sole purpose in the screenplay is to communicate to the audience with frothing hyperbole just what a monster this Michael Myers really is. It can’t be overstated how important Pleasance is to making this film into the cultural touchstone that would inspire the early ’80s slasher boom to follow. —Jim Vorel

13. Arsenic and Old LaceYear: 1944

Director: Frank Capra

Frank Capra’s adaptation of this darkly comedic Broadway play (some of the Broadway cast reprised their roles in the film) stars Cary Grant as Mortimer Brewster, one of a family of Mayflower bluestocking WASP types who have, over the generations, become—I think the phrase is “criminally insane”? Brewster, an author of many tomes on the stupidity of marriage, gets married. On the eve of the honeymoon he drops by his family home to check in with his loony and sweetly homicidal aunties (Josephine Hull and Jean Adair), a charmingly delusional brother (John Alexander) who believes he is Theodore Roosevelt, and another brother, Jonathan (Raymond Massey), who has bodies to bury and a flat-out crazy alcoholic plastic surgeon in tow. Peter Lorre plays the surgeon, who has altered Jonathan’s face to make him look like Boris Karloff (naturally). And that’s just the setup. More than seven decades after its release, this film is still snort-soda-out-your-nose funny, even though it’s tame and a bit hammy by contemporary standards. The endurance of this film is a testament to both the wonderful script and the magic of Frank Capra with a stable of talented comedic actors at his disposal (and not in the “bodies in the basement” sense). —Amy Glynn

12. The Honeymoon KillersYear: 1969

Director: Leonard Kastle

In a film that acted as something of a spiritual antecedent to the sensibilities of John Waters, Terrence Malick’s Badlands and the exploitation films of the ’70s, Leonard Kastle delivers greatness with The Honeymoon Killers. Shot with absolute care—in a verite style, unafraif to show gruesome details—and a wonderful attention to detail amidst long, lingering frames, this marks the only foray into directing for Kastle, an artist who knows the most power can be held in what he doesn’t show. Kastle’s sense of lighting is one of the film’s strengths, not to mention the rather great performances by Shirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco, playing the real couple of Martha Beck and Ray Fernandez, whose story unravels more and more through every passing act of grotesqueness and horror, their bickering throughout one of this low-budget shock classic’s highlights. —Nelson Maddaloni

11. MonsterYear: 2004

Director: Patty Jenkins

Charlize Theron’s transformation into notorious serial killer Aileen Wuornos in Patty Jenkins’ heartbreaking drama goes beyond her becoming downright unrecognizable in the role. (Roger Ebert famously did not know it was her in the role when he first saw Monster). Anything we had previously known about Theron’s persona and demeanor as a movie star she completely strips away to embody this extremely troubling, yet inherently tragic figure. Theron is completely submerged in her character. Every glance, every hand gesture and every physical tick seem to be those of Wuornos. There’s not a single moment in the film in which the actress peeks out from behind those eyes. Charlize Theron captured something essential and magical (if very disturbing)

—Oktay Ege Kozak and Tim Regan-Porter

10. The Cabinet of Dr. CaligariYear: 1920

Director: Robert Wiene

The quintessential work of German Expressionism, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was described by Roger Ebert as the “first true horror film,” although a modern viewing is understandably unlikely to elicit chills. Still, in the same vein as Nosferatu, Robert Wiene and Willy Hameister’s fantastical visual palette is instantly iconic: Buildings cant in impossible angles and light plays strange tricks—are those shadows real, or painted directly onto the set? The story revolves around a mad hypnotist (Werner Krauss) who uses a troubled sleepwalker (Conrad Veidt) as his personal assassin, forcing him to exterminate enemies at night. The film’s astonishingly creative and free-thinking designs have had an indelible influence on every fantasy landscape depicted in the near-100 years since. You simply can’t claim an appreciation for the roots of cinema without seeing the film. —Jim Vorel

9. Se7enDirector: David Fincher

Year: 1995

It’s hard to think of a movie that did more short-term damage to the length of your fingernails in the ’90s than David Fincher’s Se7en. Sticking close to detectives David Mills (Brad Pitt) and almost-retired William Somerset (Morgan Freeman) on the trail of John Doe, a murderer who plans his kills around the seven deadly sins, the film allows us to watch Somerset teach a still-naive Mills valuable life lessons around the case, which has morally charged outcomes aimed at victims that include a gluttonous man and a greedy attorney. For all the disturbing crime scenes considered, Se7en’s never as unpredictable or emotionally draining as in its infamous finale, in which Mills and Somerset discover “what’s in the box” after capturing their man. —Tyler Kane

8. The Texas Chain Saw MassacreYear: 1974

Director: Tobe Hooper

One of the most brutal mainstream horror films ever released, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, based on notorious Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, resembles art-house verité built on the grainy physicality of its flat Texas setting. Plus, it introduced the superlatively sinister Leatherface, the iconic chainsaw-wielding giant of a man who wears a mask made of human skin, whose freakish sadism is upstaged only by the introduction of his cannibalistic family with whom he resides in a dilapidated house in the middle of the Texas wilderness, together chowing on the meat Leatherface and his brothers harvest, while Grandpa drinks blood and fashions furniture from victims’ bones. Still, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre might not be the goriest horror film ever made, but as an imaginal excavation of the subterranean anxieties of a post-Vietnam rural American populace, it’s pretty much unparalleled. Twisted, dark and beautiful all at once, it careens through a wide variety of tones and techniques without ever losing its singular intensity. (And there are few scenes in this era of horror with more disturbing sound design than the bit where Leatherface ambushes a guy with a single dull hammer strike to the head before slamming the metal door shut behind him.) —Rachel Hass and Brent Ables

7. MYear: 1931

Director: Fritz Lang

It’s rather amazing to consider that M was the first sound film from German director Fritz Lang, who had already brought audiences one of the seminal silent epics in the form of Metropolis. Lang, a quick learner, immediately took advantage of the new technology by making sound core to M, and to the character of child serial killer Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), whose distinctive whistling of “In the Hall of the Mountain King” is both an effectively ghoulish motif and a major plot point. It was the film that brought Peter Lorre to Hollywood’s attention, where he would eventually become a classic character actor: the big-eyed, soft-voiced heavy with an air of anxiety and menace. Lang cited M years later as his favorite film thanks to its open-minded social commentary, particularly in the classic scene in which Beckert is captured and brought before a kangaroo court of criminals. Rather than throwing in behind the accusers, Lang actually makes us feel for the child killer, who astutely reasons that his own inability to control his actions should garner more sympathy than those who have actively chosen a life of crime. “Who knows what it is like to be me?” he asks the viewer, and we are forced to concede our unfitness to truly judge. —Jim Vorel

6. Peeping TomYear: 1960

Director: Michael Powell

In one respect, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom is a meticulous, human, thoughtful movie about the mechanics and emotional impulses that drive the filmmaking process. In another, it’s a slasher flick about a loony tune serial killer-cum-documentarian who murders people with his camera’s tripod. (The tripod has a knife on it.) Basically, Peeping Tom is precisely as silly or as serious as you care to read it, though as absurd as the premise sounds on the page, the film is anything but on the screen. In fact, it was considered quite controversial for a time—and depending on whom you ask it may still be. Understanding why doesn’t take a whole lot of heavy lifting; movies about women in peril have a way of striking their audience’s nerves, and Peeping Tom takes that idea to an extreme, giving its slate of victims-to-be little room to breathe as Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm) closes in on them, capturing their exponentially increasing fear from second to second as they face dawning comprehension of their impending deaths. It’s a tough film to sit through, as any film about a psychopath with a habit of brutally slaying women would be, but it’s also thorough, insightful, impeccably made and brilliantly considered. —Andy Crump

5. BadlandsYear: 1973

Director: Terrence Malick

Why did two seemingly normal people go on a cross-country killing spree, and what is it that makes theirs so strikingly different from all the other movies about serial killers on the run? Those two broad questions steer first-time director Terrence Malick in Badlands. It begins with Spacek’s narration as Holly; the entirety of her backstory comes from this first monologue, through which we’re told her mother died of pneumonia and how, after her death, “[Her father] could never be consoled by the little stranger he found in his house.” Then the film gives us a montage of images from this small town in Texas before introducing us to Kit (Martin Sheen), who’s shown working as a garbageman. Kit sees Holly twirling a baton in front of her house and their fates are sealed. The basic plot of Badlands was drawn from Charles Starkweather’s murder spree with his girlfriend in 1958, but Malick only uses that story as a loose frame for his big questions about the nature of evil and our compulsion to watch movies like this. “Our sense of the past is always already influenced by our present understanding of the world (we see the past through the present); and yet our present understanding of the world is itself always already influenced and determined by the past (we see the present through the past).” Theorist Leland Poague’s understanding of the “reception theory” provides an ideal framework for Terrence Malick’s 1973 debut feature. It’s impossible to view Badlands outside the lenses of his later work, but it’s also impossible to view his later work outside the lenses of Badlands. —Sean Gandert and David Roark

4. The Night of the HunterDirector: Charles Laughton

Year: 1955

Film noir or horror—in which category does Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter belong? Frankly, all such quibbles are needless. The film fits snugly beneath either appellation, for one thing: It’s a hybridized version of both. For another, it’s a masterwork, so fie upon labels. Night of the Hunter lurks in shadows and revels in misogyny. Whether you’ve seen it or not, you probably have the image of Robert Mitchum’s tattooed knuckles imprinted upon your brain thanks to pop culture osmosis. Reverend Harry Powell is quite the villain, a man as quick to distort the truth with honey-coated lies as Laughton is to distort reality through oblique perspective, unnerving use of shadows and light, and a dizzying array of camera compositions that make small-town West Virginia feel altogether otherworldly. —Andy Crump

3. ZodiacDirector: David Fincher

Year: 2007

I hate to use the word “meandering,” because it sounds like an insult, but David Fincher’s 2007 thriller is meandering in the best possible way—it’s a detective story about a hunt for a serial killer that weaves its way into and out of seemingly hundreds of different milieus, ratcheting up the tension all the while. Jake Gyllenhaal is terrific as Robert Graysmith, an amateur sleuth and the film’s through line, while the story is content to release its clues and theories to him slowly, leaving the viewer, like Graysmith, in ambiguity for long stretches, yet still feeling like a fast-paced burner. It’s not Fincher’s most famous film, but it’s absolutely one of the most underrated thrillers since 2000. There are few scenes in modern cinema more taut than when investigators first question unheralded character actor John Carroll Lynch, portraying prime suspect Arthur Leigh Allen, as his facade slowly begins to erode—or so we think. The film is a testament to the sorrow and frustration of trying to solve an ephemeral mystery that often seems to be just out of your grasp. —Shane Ryan

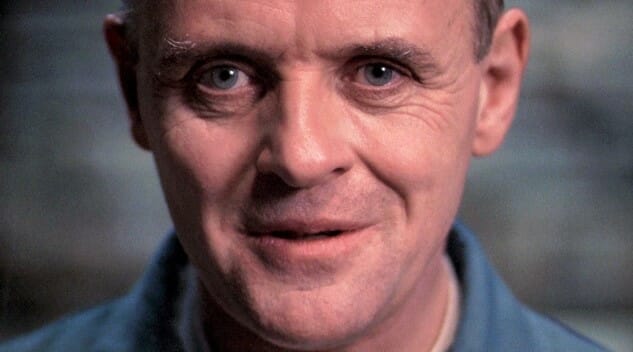

2. The Silence of the LambsYear: 1991

Director: Jonathan Demme

In the face of grotesque sequels, lesser prequels and numerous parodies, The Silence of the Lambs still stands as a cinematic work of art among crime dramas and serial killer movies, only the third film ever to win the five gold rings of Oscar-dom: Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress and Screenplay. Anthony Hopkins’ portrayal of the murderous Hannibal Lecter especially proves the worth of surrounding one of cinema’s greatest thespians with a stellar supporting team, though director Jonathan Demme deftly wields the brush of that talent to bring audiences into the dark, sadistic world of Dr. Lecter while leaving them gasping at the twists and turns of novelist Thomas Harris’ gruesomely wonderful story. As happens with all great films, second and third viewings fail to diminish the ride, but instead reveal even more subtleties of characterization. And Demme’s own style behind the camera makes the close-up world of Silence of the Lambs an unforgettable visual parlor of grotesqueries. —Tim Basham

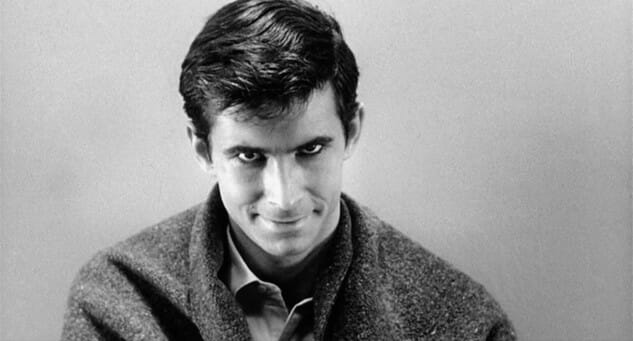

1. PsychoYear: 1960

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

The big one. The biggest one, perhaps, though if not, it’s still pretty goddamn big. Almost 60 years after Alfred Hitchcock unleashed Psycho on an unsuspecting moviegoing culture, finding new things to say about it feels like a fool’s errand, but hey: Five decades and change is a long time for a movie’s influence to continue reverberating throughout popular culture, but here we are, watching main characters lose their heads in Game of Thrones, their innards in The Walking Dead, or their lives, in less flowery language, in films like Alien, the Alien rip-off Life and, maybe most importantly, Scream, the movie that is to contemporary horror what Psycho was to genre movies in its day. That’s pretty much the definition of “impact” right there (and all without even a single mention of A&E’s Bates Motel).

But now we’re talking about Psycho as a curio rather than as a film, and the truth is that Psycho’s impact is the direct consequence of Hitchcock’s mastery as a filmmaker and as a storyteller. Put another way, it’s a great film, one that’s as effective today as it is authoritative: You’ve never met a slasher (proto-slasher, really) like Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), and no matter how many times the movies try to replicate his persona on screen, they’ll never get it quite right. He is, like Psycho itself, one of a kind. —Andy Crump