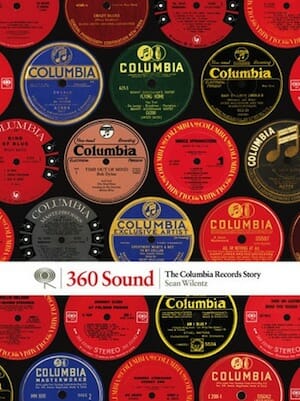

360 Sound: The Columbia Records Story by Sean Wilentz

Sean Wilentz, a history professor at Princeton University, writes on prominent American figures, including Ronald Reagan and Andrew Jackson. Along with respected music critic Greil Marcus, he penned a collection on the American ballad, and he wrote a book on Bob Dylan—in fact, he holds the title historian-in-residence for Bob Dylan’s fan website.

Wilentz’s latest work, 360 Sound: The Columbia Records Story, reports on the up-and-down history of one of the few American musical institutions older than Dylan —his label, Columbia Records. This book commemorates Columbia’s 125th anniversary.

360 Sound has presentation on its side. It’s not just a history text; it comes filled with huge, coffee-table-book-sized pictures of fascinatingly old recording machinery and gorgeous record labels. And of course plenty of superstars: seductive photographs of Bruce Springsteen, Beyoncé and Frank Sinatra, who sings into a microphone with his hands in his pockets, as if he neither knew nor cared what happened around him, the world on a string. Along with Wilentz’s writing, we find blurbs from Dave Marsh, another esteemed music critic.

You might think the history of a music label would interest only the artists who recorded for it. 360 Sound dispels this notion. Again and again, like a protagonist in an action movie, Columbia faced extinction—from competing technologies and other labels, musicians fighting for their jobs, exogenous factors like the 1929 market crash and World War II, and repeated failures to recognize newly popular musical forms, such as rock in the ‘60s. Somehow, the label dodged and feinted, grew stronger and fought back, surviving to the present. Wilentz notes that Columbia at the end of 2011 holds the title as America’s foremost label in market share, with 9.39 percent of the U.S. album (remember those?) market.

The American inventor Thomas Edison first patented a phonograph for recording sound in 1878, but he believed that recording music took priority only “behind dictation, phonographic books for the blind, and the teaching of elocution.” Edison sold the rights to his device (to a cousin of Graham Bell, the man behind the telephone), and Columbia came into being in 1887. The company took its name from its original home base in Washington D.C. Early recordings sold by the label include a “well known yodeler of the Washington police patrol” and William Jennings Bryan’s “cross of gold” speech.

Columbia survived a threat from the development of radio in the 1920s, began experimenting with electronic recording techniques, and played an important part in the recording of early jazz and blues music. Wilentz notes Columbia’s strange relationship with black music, producing “race records” that perpetuated racism and segregation but also captured important landmark moments in black music. The label did this “not because they loved music, but because they loved making money,” Wilentz writes.

While the book does not dig much further, Columbia’s relationship with black popular musical forms remained convoluted. Post WWII, although several big jazz names graced the Columbia roster, the company paid little attention to soul, funk or disco—or if it did, the artists don’t get discussed in 360 Sound. The label also found only intermittent success with hip-hop, despite that genre’s close ties with Columbia’s eventual home, New York City.

Blindsided by the 1929 stock market crash, Columbia received an unforeseen gift from the end of Prohibition—the development of the jukebox. By the mid-1940s, this device accounted for a whopping “60 percent of all the records produced in the U.S.,” writes Wilentz.

The Columbia label changed hands several times, moving to the American Record Company and then to CBS. CBS moved the operation to New York City and World War II hit not long after, restricting the materials available for the making of records. Columbia also faced a massive strike by the American Federation of Musicians, who argued that records were stealing their jobs.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-