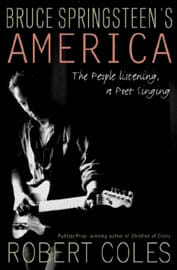

Bruce Springsteen’s America …

Is it just me, or is the critical consensus surrounding Bruce Springsteen beginning to unravel? In a Balkanized world of ’zines and microgenres—where pop music, to paraphrase Elvis Costello, is less like a charging elephant and more like water running everywhere—an artist known for his broad appeal and seeming centrality can hardly remain the big deal he was in 1975 or 1984, when the idea of a “center” still held meaning. Much of Springsteen’s perceived relevance stems from a songwriting method problematic in a hyperaware, fragmented age—those suggestively nonspecific vignettes about regular Joes and their problems, that self-consciously mythopoetic voice, the obvious (therefore “universal”) symbols. When Springsteen’s fellow Jerseyites The Wrens released The Meadowlands last September, more than one critic contrasted its personal, detailed portraits of dreams lost to the workday with Springsteen’s—and the Boss ended up losing.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-