Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant by Roz Chast

Writer & Artist: Roz Chast

Publisher: Bloomsbury USA

Release Date: May 6, 2014

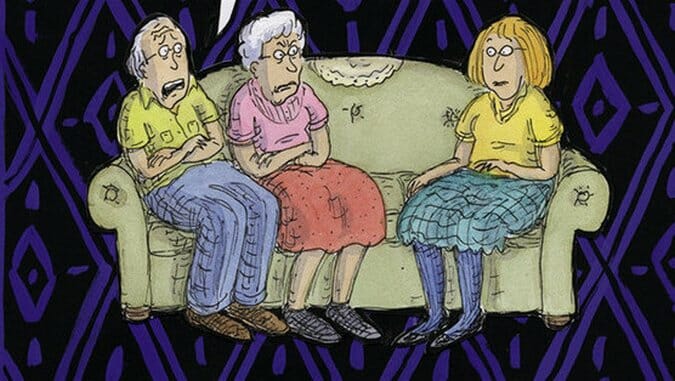

Roz Chast isn’t known to tell longer stories. In her work for The New Yorker, it’s rare she produces more than a couple pages of narrative confined to the space of a cartoon. Her work might contain a few panels, but what she conveys is essentially a single idea, not a plot. Her Marco picture books for children, about a talking parrot, are less episodic but still short. Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir, on the other hand, is a substantial book — 240 pages focused of the author dealing with her aging parents, basically easing them into death. Considering the leap required (at least for the reader, if not also the writer) to move from 4 × 4-inch square, fridge-bound clippings to such a weighty topic, the effort is quite successful.

Chast has most notably chronicled anxieties in a way that seems simultaneously heartfelt and amusedly detached. Her frazzled characters stress about appropriate responses to social situations, developments in technology and, indeed, parent-child relationships. Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? is in many ways a natural outgrowth.

One can’t help but compare it to Joyce Farmer’s Special Exits, which deals with an almost identical situation. Farmer takes a more obvious “comics” approach, her black-and-white work rendered in nicely delineated panels, her method embracing the show-rather-than-tell approach. Chast’s version of the story is messier. For one thing, as purists will no doubt complain, there is so much text. Some pages contain no drawings at all, only words. Photographs are even interspersed with lines. It’s a much more first-person account of what confronting mortality feels like, full of explicit reflections on exactly that. Plus, the drawings are less serious. Farmer certainly uses comedy as a tool, but Chast’s visuals, even if you haven’t been conditioned by decades of her New Yorker work, read cartoonish and unsubtle.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-